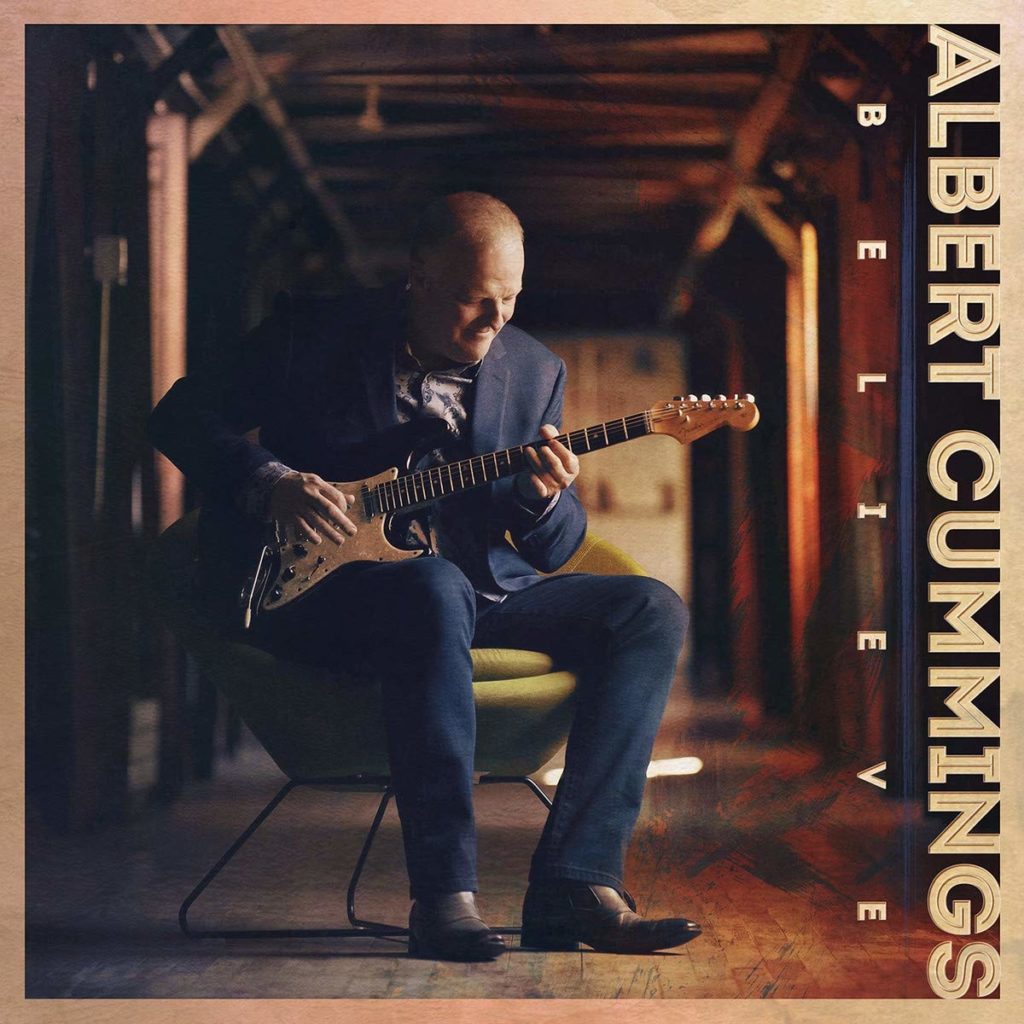

Back in February (and what a lifetime ago that feels now), Albert Cummings released his eighth album (and Provogue debut), Believe. An airy masterpiece (you can read our review here) that is more than worthy of the legendary Fame Studios (Muscle Shoals) in which it was tracked, Believe may yet prove to be the blues album of the year, and it is still a regular fixture on the stereo here at SonicAbuse. We were, therefore, delighted when Albert consented to an interview.

Albert, like his onstage persona, is alive with excitement when we speak to him. Ask about Muscle Shoals, and it’s like talking to a young boy who’s just got their first guitar. Talk about his album, and it’s like he’s still coming to terms with just how good a record it is. Of one thing there is no doubt, Albert loves the blues and his passion crackles down the phone over the course of the thirty minutes for which we speak.

The first question I have is that you went into the legendary Muscle Shoals Studios, the Fame Studios, and I wanted to ask you a little bit… people tend to imagine that studios can be quite sterile places, but when you go into a place like that with so much history, it adds something to the recording doesn’t it?

It sure does, it’s just a very wonderful place to be in. To be able to be in the music world is one thing and then, when you get into those places that are just full of musical history. The pictures on the wall, the people that have been through there, the records that have been made, the hits that have been made. I was absolutely star struck the whole time, just to be involved and to be in the building.

I think you said that, on one of the days during the recording, you joined one of the tours being given by the owners – it must have been weird to join a group of people looking at the building as a place of history while you’re becoming part of that history…

Yeah, so it’s not a huge studio. When they were doing the tours, when you record there, they tell you up front, they say they’re going to do two tours every day; they take five-ten minutes and they just walk people through. It’s only a few rooms in the studio, so it doesn’t take long. So, that day, usually if we knew the tour was going to be at three in the afternoon, we’d plan accordingly and at two fifty, we’d all stop and go get a coffee or whatever, and this day (I don’t know what we were working on), we were trying to get something down and one of the engineers was actually giving the tour and he said for us just to stay put and he’d run the tour through. So, we all stayed at our stations and they ran the tour through, and our keyboard player on the session – his name’s Clayton Ivey, who’s one of the second generation swampers from the original studio band – he was sitting at a little Wurlitzer piano the whole time we were tracking and the tour guide said “here’s the piano that Aretha used when she cut Never Loved A Man”, and Clayton instantly went into the riff of that song and it was right then that I was like “oh my god!” I really hadn’t put it together where I was, and I was like “oh my god! That was cut right in this room, on that keyboard, that we’re using right now!” From then on out, I had a little different appreciation, but it never hit me until that moment. What a joy it was.

It sounds amazing. Being in any studio and the creative vibe you get anyway is always very exciting, but to have that legacy and history is something truly special.

For sure. For sure. There was another moment when I was working on some guitar and I looked on the wall and there was a poster of Gregg Allman and I looked in the back of Gregg and it looked very familiar and I looked around and I was standing in the spot where the photo was taken and I was like “wow!” it was so much fun.

I know that the blues, probably more than most other genres, has a history of artists playing covers, partly to pay tribute to what’s gone before and partly to reinvent songs in their own key style. When you’re thinking about covers, what do you look for that makes you think it’s something to which you can add your own stamp?

Well, I think you’re right on that… when I went to do this album, I went to do an album of all cover songs. I’d done eight CDs prior to this one and usually I do one cover on each album. And this one, I noticed that radio stations and TV were giving me a lot more play on the songs with which they were familiar, because you’re right, most artists throughout the years have always paid tribute to each other and done their songs, so I figured I’d do a whole covers album. So, I picked about thirty songs that I was going to do and then maybe pick those with the band and the studio musicians, and when I got there, we went over the list, we started to play and jam a little bit and I realised I had this incredible group of musicians, with this whole different sound – because of Muscle Shoals, it has its own sound down there – so, I instantly said to myself that I couldn’t do all covers. I had to do some of my own songs, I just had to. But, when I think about doing someone’s cover, to answer your question, I first pick an artist I love, for sure. Then I pick someone who has inspired me and then I pick a song that I think I can put my own stamp on, like you said. I play it the way I hear the song, and what I’m hoping to do is, maybe… if that song was first done in 1962, I just want to play it in a more modern way, but not take away from the song’s character, but I want to present it to the modern world, and if the song was done in 1962… well, we’re no longer driving 1962 vehicles or using 1962 appliances… we’re using what’s now, and people are used to now. So, if I’m going to bring people to my heroes, and pay tribute to my idols, then I need to bring it to them in a way that’s a modern way. And I don’t know if I’m right or wrong with that, but that’s how I feel about it, so I try to bring it in a modern version of what people can relate to now, but still pay total tribute to the song, and to the person who did the song. I don’t know if that made sense, but that’s my thoughts behind covers.

It makes perfect sense. For me, at least, the big challenge is, as you say, pitching it just right so you’re not using the atmosphere or the soul, if you like of what went before, but you’re bringing it into the present.

Yeah, right. I’m not a big fan of trying to recreate exactly note for note a cover. If I want to hear the original, I’ll go hear the original. No one’s going to do it better than the guy that did it originally, so, you have to… it’s a tricky situation, because you have to pay respect and hopefully you don’t mess the song up! But you’re right, if you listen to B.B. King and Buddy Guy and Muddy Waters, and Eric Clapton even, they’re all paying tribute to these songs and they put their own versions of them and it’s fun. I had a conversation with B.B. King one night and we were talking about guitar licks and, I think B. B. was joking around about how he was going to watch what I was doing. He was always… he had such a great sense of humour, he was going to watch what I was doing and try to copy a lick… and obviously he was joking around, because there’s no greater guitarist in the world, but that was the humble sense of humour that B. B. had, but then he said to me “Albert, we don’t steal licks – we just borrow them.” We all learn from each other, that’s what he’d say.

I was speaking with an artist on similar lines, and there’s something in the blues where there is this universal language of the blues – licks which are instant familiar – but what makes a great blues artist is the ability to speak that language with their own accent…

That’s a very good way of putting it, a very good way of putting it. Exactly. I’ve always thought of the blues, the music anyway, as a simple expression of feelings and if people are being honest with feelings, there’s no way to replicate that. That’s an individual approach, it’s an individual artistic approach and if people go to their own feelings, and those are personal. So, if people do that in their music, they should have their own style of music. At least, that’s what I try to go for.

To pick one of the covers specifically, starting the album with Hold On, it put a huge smile on my face – you’ve got that brass section raging away… it’s a brave song to cover, I think, but it’s pitched just right and it sounds like you had so much fun playing that in the studio…

Thank you – we did. You know, people say “well, that’s not blues, that’s soul!” I don’t really believe in the lines of the genres. It all stems… all of that stems, everything we know as music from country to soul to rock to disco to rap… all of it started out with the blues guys, I think. Everyone is influenced by someone else, it all started somewhere, and B. B. King was a real big part of that in the beginning. Of course, he had his idols prior to that – the big band orchestras and things, but B. B. was very influential in starting the whole ball of wax and those songs and I was very inspired by the version of Hold on that Eric Clapton and B. B. King did together, on Riding with the king, I think. I’m not sure what album, but that’s where I really fell in love with that song, and I had to do that song, it’s one of my favourites.

I always appreciate it when someone gets the brass section in, there’s something so warm and organic about a brass band sound that instantly brings blues and soul to life, I think.

It does! It does. B. B. was probably the first guy, well definitely the first guy in the modern blues as we know (and I mean modern from 1950 on) because B. B. was inspired by the big blues orchestras – Louis Jordan and all those guys. That’s always been a part of the music because, before amplification, that’s all they had, and it’s just a timeless part of the band and, you know, I can see myself with a horn section with me someday but I’m not quite ready to start touring with a horn section yet, but on this album I wanted to have one because, just as you said, it makes people smile and want to move a little bit.

Thinking about recording in general, it’s quite difficult sometimes, especially for an artist who has a reputation as a live force as you do, to capture that live vibe on record – how do you approach it? Do you aim to have the album as one thing that’s a bit more layered and then digress from that live, or do you try to capture everything live in the studio?

I try to do it as much as I can live, but it’s not as easy as it sounds, and for me, I seem to be able to play better when I have pressure on me. They say: “pressure makes diamonds” and I totally believe in that statement. When there’s pressure, there’s something that takes over me and I don’t have to worry so much about getting things right, I just do it. But it’s nice in the studio, because you have a safety net and if you mess things up, you can go back, and nobody knows. So, you know, why not? If I have a safety net, I give it all that I can give it and shoot for the best, but there’s definitely… I totally believe in the saying; “if you’re thinking, you’re stinking!” If you’re not trying to create something and, you know, play it live, it’s very hard to get a sense of excitement when you’re just performing it and doing something you’ve practiced over and over and you just perform it. It’s better if you come up with something, and you get lost, and the red light’s on and the recording’s going. It just creates a sense of pressure, that always makes for a better sound, I think.

There’s a real danger, especially in something like the blues, and other genres where there’s that live thrust (punk would be another one) and there’s a danger to over-thinking and killing the vibe.

Yeah, it’s true. It’s exactly what happens. You just can’t be too comfortable with it. I think you just have to be on the edge. Even at my shows, I just walk to the edge of the cliff and jump off, and I just hope that I catch a branch, you know, because I don’t want to be so comfortable that it becomes boring, because if it’s boring to me, it’ll become boring to the audience.

Do you find, though, that when you play live that songs tend to expand out; because it seems that, especially with the blues, songs that last four minutes on record can double or triple in length when you’ve got that interaction with the crowd?

They certainly do, and I try very hard not to let that happen! Even… I’ve been to shows, where even I’ve got sick of the guitar solos [laughs]. It’s like, “OK, this solo’s been going on half an hour already, I’m going to go somewhere else, because I just can’t take it anymore! I wanna hear something else!” You have to keep the listener in mind, and you know, it’s a balance that you have to find. This is an interesting album for me in another way, because I didn’t set out to make a guitar album. People know me as a guitar guy, and I don’t… I mean, my wife yells at me all the time because I don’t even see myself as a guitar guy. My guitar is one of my tools. It’s my voice, my song writing, and my guitar and I didn’t want to go make an album that was just all guitar. I’m so sick of these albums, there are so many of these albums being made and they’re all “look how many notes I can play; look how many licks I can do!” and I don’t care. I want to know if they can gel with the band. I want to hear the band. I don’t want to hear the guitar, and I’m a guitarist. Again, it’s just my opinion and we all have opinions, but I just wanted it to be an album of songs that people could listen to and not worry about what the guitarist is doing.

It’s interesting you say that, because one of the songs I picked out from this album is “Queen of Mean” and my thoughts about that song was that it was really nice in the way it sits back and the brass and the vocals do the bulk of the talking in that song.

Right, well, Carlos Santana had a wonderful saying (and I hope I get to meet him someday, because I’ve never met Carlos), that “if you can’t compliment the music, then turn down.” And I totally believe that, it’s like… I wanted to play with the band. I didn’t want it to be a band playing with a guitar player, I wanted to be a guitar player in the band. You know, I can admit that I’m guilty of being the out-front guitar at shows, and I tend to play too long and too loud and blah blah blah, but I just didn’t want to do that on this album. I wanted to really focus on making an album for the listener, not for the guitarist.

I think it’s a difficult balance to get, because in many places there are times when you want and need that gun slinging guitarist approach, but as you said, and I’ve always believed, that the solo has to serve the song first rather than the ego. But I think younger guitarists can get lost in the technicality and lose the soul in the process.

Right, you and I are on the same page there. You hear the new album’s coming out and, you know, even some of the bigger acts, too much over-produced guitar – just lay back, let the band talk, let the song speak for itself… but, you know, there are people who would totally disagree with me, and that’s fine. I’m a guitarist, and I come from that angle, so it’s kinda hard for people to disagree with me – if I want to come at it from that angle, that’s what I’m going to do. I certainly could put out an album of just guitar, but I don’t even care. I’m not obsessed with trying to be the greatest guitarist of all time. There are plenty ahead of me that have already taken that role.

One thing that interested me, is that you didn’t set out playing publicly until you were twenty-seven, but (and I hope you’ll forgive me), but in music, which is traditionally thought of as a young person’s game, that’s quite late to kick off on stage, isn’t it?

[Laughs] well, I think… the age of most of the… Hendrix, Joplin, Jim Morrison – the twenty-seven club? They all died at twenty-seven, their careers were over, and I didn’t start until I was twenty-seven, so I guess I missed that potential of dying young! I don’t know…

Well, that stands as an advantage!

I started way late., I had no intention of ever getting into music. Music found me. You know, as I started to play and I remember I was thirty-five / thirty-eight (and I’m fifty-two now) and people would say: “Albert, you should have done this when you were twenty” and I simply say, I didn’t know who I was at twenty. How could I have been real with my music or given you exactly what my heart feels because I didn’t even know myself at twenty. I thought I knew myself at twenty, but now that I’m older, I was just talking about this yesterday, I was a little kid at twenty-years-old. I don’t know, it’s just the way it happened for me, that’s all. There’s nothing I could change about it.

It’s an interesting point that you make – as much as anything else, making music requires time, dedication and, depressingly money and there are a lot of cases that, when you’re young, you don’t have the wherewithal to go out and do this, so leaving it until later makes a lot of sense.

Yeah, it’s very true. And also, even take the money out of it and everything else out of it, and life experience… my songs are based on my life and most of my songs come from something that happened to me or something that reminded me of something, or along those lines. So, my music comes from somewhere and, you know, when I was twenty, I didn’t have that life experience, I didn’t have that many topics to talk about. I didn’t see great days and bad days that dragged through the mud and all this stuff that goes with living. It’s just part of it. I think, especially in the bleus, it helps to have some… how do I say it? It helps to have the treads on the tire worn out a little bit.

It’s the difference between becoming a blues cipher, where you mimic other people’s experiences and actually living the experiences yourself…

Exactly. That’s… you know, you hear a younger guitarist comes out and someone gives them a song that only a fifty-year-old or a forty-year-old would understand and the poor young kid is trying to sing it, but he has no understanding or passion for what he’s saying and it’s just not believable, you know, to me. And, it’s like, it just takes some life experience, I think, to feel and understand emotions and I don’t think that, when you’re young, you have the ability to really read those emotions. We might feel them, but we don’t really understand them, I don’t think, so… it helps to be older and I think that’s why B. B. King just got better… and look at Buddy Guy, he’s in his eighties… that doesn’t mean you have to be eighty to understand the blues, but certainly their lives reflected their journey.

The blues particularly, you can more or less play until you drop… it’s a genre that allows the fire and experience to continue to flow – it would be difficult, perhaps, to be playing in Slayer at 85! The blues, you can speed it up or slow it down and it seems to work…

Exactly.

You’ve only just signed with Mascot for this record, how did that come about?

Well, I always wanted to work with them. I’ve always admired them, and I certainly admire the people they have on their roster and I did this record and I didn’t expect to get a label with this record because of the covers. Labels usually want to have original material because of the publishing and all the stuff that goes with it, it’s better for the label. So, anyway, I sent the record to Provogue and my fingers were crossed but I wasn’t really expecting anything, and they called back and said “We’re in!” and I said “Yeeeessss!” and I was so happy and I’m still so excited about it. I just love it; I really love the whole process and the whole thing and when someone is willing to take a chance on me like that, I’m very grateful.

It’s a strange experience, I think, when you finish a record and you’ve spent so long on this thing that represents a portion of your life and you have to start passing out, either for reviews or to potential labels and suddenly this thing that is your is out of your control, and there’s an element of fear there as well, isn’t there?

Well, there certainly is. Especially when you’re introducing your own music because, you know, talk about exposing your belly. It’s like you create this stuff and then you put it out there and you just hope people like it, you just hope they do and you try to give them something that they will like. Early on I worked with Double Trouble, Stevie Ray Vaughan’s back, and I remember Chris Layton, early on (he’s the drummer and a friend of mine) – he said: “just keep in mind, if you believe all the good, then you have to believe all the bad!” In other words, what he was telling me was to stick on your own course, but not to get tied up with what the reviews say, or the critics say. You have to do what you believe in and stay your course. I’ve always remembered that, and I’m always thankful that he told me that because it’s true. You can get a bad review and feel that you’re terrible and then the next day you get a great review and, you know, it’s in the eye of the beholder and not everyone is going to like it and I’m just grateful that people took the time to listen. It is what it is.