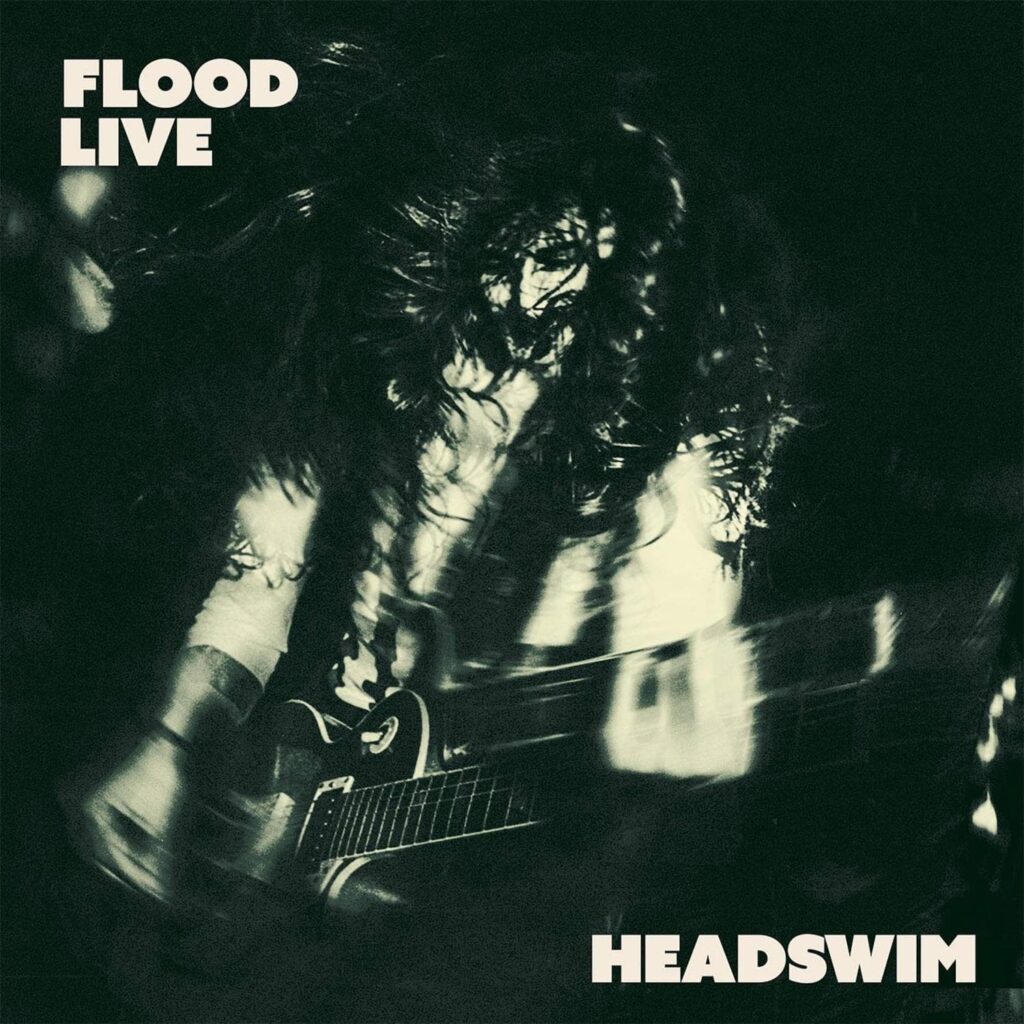

In 2023, some twenty-five years after the band had come to an ignominious end – the victim of an industry eager to pump money into a potential band and equally eager to drop them at the first sight of financial underperformance – Headswim took to the stage at the Camden Underworld to play a one-off gig in celebration of Trapped Animal’s stunning anniversary reissue for Flood (reviewed here).

An emotional night, it not only saw the band reunited, but also their former tour manager from the Despite Yourself years, Andy Shillito, behind the desk. Andy, who never thought he’d see the band back together, recorded the whole thing and, in early 2024, we were treated to Flood Live, a double vinyl set (reviewed here) that captured a truly special moment for band and fans alike.

We caught up with Andy as he caught his breath following a lengthy tour with The Darkness, also celebrating a major milestone, to discuss the band’s history, their reunion, and the recording of this very special album.

Hey! I’m sorry it’s taken a while to get this together, but I really wanted to get hold of the album and listen before we spoke. Anyway, it’s not that usual to get to speak to the sound engineer and tour manager. So, it’s really nice to kind of get behind the scenes a little bit, especially as you go back with Headswim to the Despite Yourself days. So, at what point did you get involved in doing this reunion show? Were you brought on board from the beginning, or were you added later in the discussion, or how did you get pulled back in?

Well, I worked with them… I started working with them on Despite Yourself back in ’97, I think… the end of ‘97… and I got the gig through Sony – Nick Mander who signed them – and then we did all the stuff together. I had bumped into them as, I think, as Blinder; back when I had a PA, and I remember them walking in, and they were only young and already… I mean they left an impression on me then – I remembered them, as they were just astonishing and so, we kept in touch.

I worked a bit with Dan live on some of his solo stuff with Black Car and… well, I suppose it was all under Black Car, but they did like two albums. He did a few gigs in London at the Barfly and stuff, and I did a bit – I kind of tried to manage it at one point, and… I kept in touch with Clovis once a year. Me and Tom would speak once every two or three years maybe. Dan would be once every six years…

And Nick I used to see at various festivals because he plays keyboards with Mew. There was a time when I was working with a girl called Lissie (’cause I mainly do live stuff), and I used to tour manage and mix this girl – she played a sort of indie-country, which got quite big in Norway; and Mew were quite big in Norway, so I used to occasionally bump into Nick when they were headlining, and we were on at like 2:00 in the afternoon!

So, there was a kind of loose connection, we always stayed in touch one way or the other and then it happened, and I just got an e-mail or a call. I think it was an e-mail from Clovis – he said they’re doing a gig would I like to (and be available to) twiddle the knobs and I was like: “yeah, absolutely!”

And it turned out that it was the day before I left for a tour of America with The Darkness, so it was just right really. I went into London and did it, and I got one of The Darkness’ guitar techs to do backline, and then we went to a Heathrow Hotel and flew the next day. So, I was involved in it from the point that it was already organised – that it was going to happen; then they got in touch and asked if I would come and look after it and look after them. So, I jumped at the chance ’cause I knew that… or I was pretty sure it would never happen again. I mean I didn’t ever think it would happen at all so, you know, I was actually looking at alternative flights the following day if I couldn’t make it or if we had you know… or if I had time to fly to America another day to do the other tour. It was that important to me, really. I just wanted to see it happen again.

I think the band, in an interview, said that you kinda surprised them with the fact that you were recording it, is that right? Did you drop it on them at the last minute?

Yeah, I suppose.

I mean, I remember I didn’t tell them immediately, because I wanted to price it up first; and then I spoke to Joel (Trapped Tiger), and he said that they didn’t really have the money and I just thought: “I’m just gonna do it”, because I didn’t think it’d ever happen again and, you know, I’m not getting any younger, and I just thought I wanna do it.

I moved to Norfolk a couple of years ago and I built a mixing room in the house. It’s a tiny little house, but I turned one of the bedrooms into a mixing room and I just thought, you know, this is something that I can do that I really care about or, you know, if I’m paid. And nobody’s on my back over time or what I do or how do I do it. So, I just got in touch and said “look I would like to record it, do you have a problem with that? I’ll pay for it, and you know, if it’s any good we’ll talk about it afterwards”.

So, yeah, I mean I didn’t surprise them at the last minute ’cause the thing is about things like that is, the last thing you want is for the band to be conscious of the fact that they are being recorded when they’re doing an important gig. You really just want them to be able to relax and enjoy themselves, so that’s why, when we set up, I said to them “don’t think about the vocals! Just do the gig because, in a place like that, you know, the chances are we’d probably going to be redoing the vocals anyway because of spill and stuff – just concentrate on putting the energy into the gig and, if everything else is alright, we’ll overdub vocals. And, if it isn’t up to it, we’ll just trash it and I’ll have, you know, lost money… unfortunately!”

So, I think I told them a couple of weeks before I think in terms of sort of recording.

What did you actually pull off the desk – did you have like multitrack feeds coming out, or sort of mixdowns or how did you go about it.

Honestly, I don’t want to be thinking about that when I’m mixing the gig, so I got somebody else in and, these days, I’ve just been doing it on all The Darkness’ Anniversary shows. Pretty much all of them have been recorded, but I did that; most of the modern digital live desks, you can take an ethernet cable and just send every channel, after the preamps I think, into Logic or ProTools or whatever. But I paid a guy to do it. I took everything – I took every mic and then four – 2 audience mics, I think, 1 in the centre of the room, one at the desk. So, yeah, absolute multitrack.

It’s one of the best live recording I’ve come across, particularly when you think about how scratchy and raw the guitars are when Headswim play live.

Thank you. I’m proud of it and I worked on it for quite a long time. I mean, I don’t know how long you want this interview to be, but I can talk through all of this!

I started my career doing this. I was a musician, but I started my career live recording gigs in Reading. And then eventually, because I had mics and a desk, one day the PA didn’t turn up, so they asked me to do the gig and mix it. So, then it became my gig and I got asked to mix bands, which was in something like ’92.

But my experience of that and of mixing things is… the best way to do it is to get the bulk of the work done in the first six hours, and then leave it for a couple of days, and then go back, spend two hours on it, and then leave it, which is what I did with this album over a period of months ’cause I was touring at same time. And then, when I realised it was getting serious, I needed to really get in there. So, the last bit took another sort of three weeks, really. It was taking me two days a track to get right in there and clean up noises, and little bits of surgery, like I did with the solo in Torniquet. He hit a proper bum note and then the other one didn’t come out right, so I had to get my scalpel out and copy a note over and elongate and that sort of thing, to get a complete solo out of it. That took quite a long time, but I’m not fast. I’m not overly experienced at mixing in the box. So, it took quite a long time.

It’s interesting about the guitars, because one of the early mixes that I did, I sent to the band as an example of what it would be like before I spent time on it. And then I did a secondary one – I was only doing the first two songs (Soup and Gone to Pot) – so, I did another mix of Gone to Pot, and everyone said “yeah, it sounds great”. But then Nick came back to say he preferred the previous mix, because the guitars on the first version sounded raggedy and raw, whereas the ones on the second version sounded lovely, but a bit too posh. And I had poshed them up a bit.

So, I think that sort of thing is really important. That you either speak to fans of the band, or you reference what it is that happens live that people like. If you’re doing a live record, you need to figure out what it is that happens live that makes it as exciting as it is, because it’s very easy when you’re in the studio to polish things too much. And I’d done that. I’d taken some of the gnarly frequencies out of the guitars, so it sat better with other stuff, whereas Nick came in and said he preferred it when it was less… nice. And he was right, you know. He was absolutely right. So, it’s interesting that you comment on that, because I would not have picked up on that.

Then, that became the template for everything else – when I started again, I went back and started with that guitar. Because when you’re mixing stuff, particularly live stuff, you’ve got to kind of pick something to hang everything else on. And, depending on what it sounds like, it dictates how the vocals will sound. Because the way I do it is live and in the studio, each thing has a little bit of frequency that belongs to it, and nothing else is allowed to have that. So, I take out 2.5K in just about everything. And then, if I need the vocal louder or clearer, I’ll let the vocal have a little more – because that’s the frequency that’s the most audible to the most people. So, that’s what I’d done.

So, I had to upside down that, and start again, and give 2.5K to the guitar so it sounded gnarly, and that worked really well, because I was then able to get a more pleasant vocal sound, that didn’t have that bit of gnarl in it.

I grew up, kinda getting into bands off the Peel sessions and stuff. And there was always that great juxtaposition between the album sound, which (as you say) was often very polished, and the session / live sound. So, particularly Despite Yourself -it’s got that late 90s sheen to it, not dissimilar to what Radiohead were doing around that time; and then you hear it live. And there were a whole bunch of bands like that – Elastica and Linoleum were so different live to on record, and that’s why I gravitated to this album, because it has that session vibe.

Yeah, I think you’re right. Particularly in the 90s, and it was really because of the advent of British bands like Bush having huge financial success in America. And the Americans didn’t want that – they didn’t want the gnarly British post-punk edge. They wanted what Americans want, which is safe, comfortable rock music for the middle classes that sounds like FM radio. Steely Dan! And I love Steely Dan, but historically, engineering-wise (and I’ve just been reading a book by one of the Beatles’ engineers), technically, the Americans had mixing desks and recording gear that were much smoother and got more bottom end and nicer top end. And that’s what their sound became, and still is. Whereas the English stuff was much more medium-wave radio, so much more in the middle frequencies. So, that was responsible for that.

There were bands likes Sensor in those days that were really in your face live, and then you heard them on the radio, and it was so difficult to get it across. And the real nail in the coffin for all of that was the Nirvana stuff, where Steve Albini went “I’ll just record what you do”. And the record company hated it, but it worked, and that’s why it worked.

I think, as a band, and particularly Dan – back in those days of Despite Yourself, where we spent practically the whole year in America, and we only did one tour in England, he was very aware (I think) that they were being asked to be like that and he found that very difficult. From a sound point of view; from a performance point of view; from a clothes point of view; from a haircut point of view. The whole thing was a bit like – it was everything that he was screaming about disliking. And I can’t speak for him, but I did have to tour manage them for a year, and he wasn’t happy about it.

That whole sonic thing – the clearest example you can see of that is the Manic Street Preacher’s Holy Bible reissue, which included the UK and US mixes – with the latter really smoothing that sound. To my ears it’s practically unlistenable in comparison, but it captures that juxtaposition.

Gold Against the Soul, which is in fact… I don’t know a lot of Manics’ albums, but I know some of their stuff. I do love Design for Life. But Gold Against the Soul I bought straight away because it sounds like a rock album, but it doesn’t sound like the Manic Street Preachers [laughs]. It sounds like… I don’t know what it sounds like – Stone Temple Pilots?

You know, I love it. I love the song construction, I love the sounds, I love the solos, but it’s not the Manics. It’s their attempt at being forced to do that thing or being asked to do that thing and acquiescing. I mean, in their case, probably they acquiesced, it didn’t work, and they went “right, fine, we’re not doing that again”.

And I think that’s where… we’re well off the subject of this album now… but that’s when you win. If I look at all of the bands – Radiohead… The Darkness… everyone was telling them “You can’t do this… it shouldn’t sound like this… we can’t sell this…” But, if you do that and you have an identity – like Status Quo did, like the Beatles did – so many bands that have longevity, either live, or in a record-selling environment. It’s because they do their thing. It’s like the sound of someone’s voice – only they can do that. So, you’ve got to stick to that, really. Because, if you win; if you’re successful at it – you can do it. You can keep doing it because it’s naturally what you do as a unit. It only really gets fucked up when record companies and producers get involved and think they can sell it into an area that, the band… you know, it’s not built for that area. They’re trying to put a Ford Escort on a racetrack, but that’s not what that car does. This car does this… and if you put it in a race with other cars like it, it’ll win.

But there you go, that’s the way of the world.

So, once you got the basic mixes done, did you, in the end, have to do any overdubs?

We did all the vocals again, apart from Down, which he refused to do. He said: “I’m not doing that again, it’s just shouting, and I think what’s there is alright.”

I didn’t play him what he’d sung live, I just listened to it and decided that we couldn’t use it. And everything else was so good, it was like, if we do this, we’ll have to do the vocals again, but I gave him two runs at each song. And I didn’t want him thinking about it too much and if it was out of tune, it was out of tune. We didn’t go at it line-by-line and we didn’t spend ages doing it. We just had two…

I think the initial one we did, we had four runs to get a feel for how it would be. Then I scrapped all of those, gave him two goes and, if there was a little thing that was really out, we’d drop it in, but otherwise it would be as-is, because I didn’t think it would work if it was too good.

And he’s good anyway. He’s very good. So, it needed to be that thing and, again, I’m pretty old school with things like that. I don’t believe in perfect records. I don’t like them. I remember reading something about Elton John, years and years ago, and it was the producer or him saying that he would go to the studio, put the track up, and do three takes, and then leave.

You get something on the first few takes that you don’t… you get emotion on the first two or three and a little bit of the feeling of someone walking on a tightrope and, once that goes, it’s kind of over for me. It’s pointless because you’re not capturing something that’s moving.

My examples of this sort of stuff when I’m having to talk people into it is: if you listen to Are You Lonesome Tonight by Elvis Presley – it’s fucking heart breaking. But the reason for that is that there’s probably forty people in a room who did 26 takes of it, and they chose the most emotive one, but everyone was doing it at the same time. That’s a piece of performed art. It’s not a piece of perfected work and that’s why it’s so moving. And the Ramones, and the Sex Pistols – terribly produced! Terribly mixed and incredibly popular. Because it moves people. So, that was very important to me. The rest of it had that, we couldn’t tack on a fucking studio vocal that’s beautiful and perfect.

There seems to be a lot of push and pull over that. I was at a festival last year where one headliner played a set that was stripped of technology; it was raw and ragged as hell, but you connected with it. The other played a set like a computer game – it was technically and sonically perfect and choreographed to the nth degree, and by the end of it, it didn’t have an ounce of feeling. And, I guess, if records are polished to such perfection, then audiences expect the same from the live show, so you really notice it when a band pushes the other way and I gravitate towards that.

Yeah, and I think people always will – because it’s human.

I hope so – it’s kind of soul destroying. But, of course, getting some overdubs are important, because (particularly with Headswim), the vocals are so important and when you play live and you’re throwing yourself around, inevitably you go out of tune or out of breath, or you fuck up lyrics, or whatever. And, of course, onstage monitoring can also hamper how you sound.

We struggled with the guy that night. It wasn’t easy. I often do monitors for The Darkness from front of house or set them up on stage. If a person’s never worked with a band before, it’s difficult for that person to accurately do what they need, and Headswim hadn’t done a gig in front of people for twenty-odd years.

So, we did a soundcheck, everyone said they were happy. But then, you get in the gig and there’s 700 people there screaming, and they’re fucking loud, and your adrenaline’s up, so your ears aren’t working the same as they were. And there’s nothing you can do about it. You’re in the headlights and you have to perform a gig, so off you go. That, and the fact that Dan now has a hearing impediment in one of his ears which, depending on the frequency and the volume at any given time will alter the pitch that he hears in his head. It was not easy. Sometimes he was right on it, sometimes he was not.

But it was an important to record to me. If it was going to come out, I knew they had to be happy with it, and I knew that it was important to the fans. I would have hated to have listened to an album by a band I really loved, where there were things that were unpleasant to hear, spoiling an otherwise great song.

So, yeah, it had to be done. I think we did it in the right way and I’d do it again. I’d definitely do it again, and just say to somebody “just have a go. Have a couple of drinks, do what you need to do.”

And I only stuck an SM58 in front of him. We were in a room, I had a mic on a stand, we both had headphones on, I had a computer, and he just did it. And that’s the way to do it. I didn’t know if it was going to work [laughs]. But, once we’d done one, it was fine. And I think we did it in two days. We did four or five one day and the rest the next, and then he went away. And I didn’t even bother listening to it. I’d listened to it while he was recording and if I didn’t feel uncomfortable while he was recording it, then I knew it was enough.

And there’s absolutely no retuning on anything. The backing tracks -the instruments – there are probably eight bars of keyboards on the whole album that I massaged a little, timing wise. The same on guitar. And probably only four bars of bass. And it was literally moving a note, a bit, just to get it in the right place. Stuff that people would probably never have heard anyway.

I guess, any changes that you make, have to be invisible because once it becomes visible, that’s when you lose the audience.

Yeah, and the other thing is, and I’ve done this before – once you start moving stuff (and I do everything by hand, I don’t even know how to grid up a piece that’s not been made to a click) – what I know is that, once you move one thing, you then have to move everything else. It might be something that’s out of time in four bars, and then you move that, and then you decide to do the whole song. Then, all off a sudden, everything else is out, so you move everything else, and it takes three days, and then you listen back and it’s soulless shit!

If you isolate the playing on a Stones record to the two guitars, they’re just out of time. They’re all over the place. Put the drums in and they make a little more sense. But it doesn’t make sense until you’ve got all the instruments in. And all the soul records are like that. I’ve seen when they’ve stripped stems out of Otis Reading, Marvin Gaye, and Stevie Wonder, and if you just put the drums with the shaker and the guitars, it’s a fucking mess. But when it all comes, there’s a coherent feel, where nothing sounds out of time with anything else. But, actually, they’re all slightly out of time.

But, again, that’s the human thing.

Yeah, it’s that swing, and it makes a huge difference to how you experience an album.

Yeah, and effects and things. Going back to the album. When I mix live, I’m pretty much two reverbs and a delay, and I didn’t do too much more on this. There’s a snare reverb – a short snare reverb. And then, I’ll put a big reverb, like 2.5 seconds, and anything that needs a big reverb on it, it goes in that. I didn’t spend a lot of time on anything. There are a few delays I spent a bit of time on, but that’s kind of one of my things.

It’s basically just them playing, with a little bit of the room in and a little bit of the desk, as well. And that’s it really.

So, how did the band get involved with Trapped Animal?

By the time I got involved in this live thing, they were already involved with Trapped Animal and, as I understand it, but I can’t speak for them, Joel (who runs Trapped Animal) was a fan, and he started a Headswim Page on Facebook. This is what I understand, but you’d have to talk to Clovis to find out. But, I think, what happened is that Joel started the page as a fan, to see if anyone else remembered them, and it just seemed to happen at the same time as Headswim got their masters back. And then Joel approached them, I think. But this all happened before I got involved.

And, of course, back in the day your tenure started after Flood – because they went on hiatus, and then came back with Despite Yourself.

Yeah, they’d been on a break – are you aware of why –

Yes, their younger brother tragically passed away.

Yes, that happened, and I wasn’t around then, but that had happened.

I got involved just before Despite Yourself came out, via Sony. So, the first thing I did was the EPK of them at London Bridge. It’s kind of a studio set up, but they’re playing live. They did Wishing I Was Naïve, Tourniquet and something else- there were about four songs, I think. So, that was my reintroduction to them – I went down and set up the monitors for the live room. I didn’t have anything to do with the recording or mixing, somebody else did that.

Then, I went on to work with them because we got on, I suppose. I liked them and the guy at Sony, and the manager at the time, asked if I wanted to do some gigs. So, we did that, and it was a year-and-a-half of mainly touring in America with Kula Shaker, I think. Then Brad. Then Catherine Wheel. We did a couple of tours where they were headlining smaller places. Then we did a run of festivals in the UK.

Yeah, you did Reading – I saw them there!

Ah right, OK. I remember getting a call towards the end of the summer from the SKan PA people. I lived in Reading at that point and they’re now a massive company, but they used to stuff at Glastonbury at the B stage, which I think was the John Peel stage back then, and they got in touch to say they were really looking forward to us coming, because they’d heard down the grapevine that Headswim were one of the best bands at the festivals that year. We were opening nearly all of them, I think. I remember doing V festival, Glastonbury, Reading. I can’t remember what else was going on then, but we did a lot of them.

Was Phoenix still going on then?

Hmmm, maybe, they were opposed to Reading, weren’t they?

Yeah, it didn’t last long. I remember they crashed in ’98, because some of their acts ended up at Reading – it was the year Beastie Boys and Prodigy clashed over Smack My Bitch Up. Maybe ‘97 was the last Phoenix…

Yeah, Phoenix got set up by Will Power when the guy who owned the farmland gave Reading Festival to someone else because they offered him more money. I think it was Will Power set up Phoenix, because it was logistically as close as a band could be (because there’s always a rider about not playing within a set radius before or after the festival), so he picked this place that was just outside their radius, and it was his idea to starve out the Reading Festival, because Mean Fiddler would have access to all the bands and the new guy would just get fucked. Which didn’t happen. I don’t think you could play both festivals because they were rivals.

I remember Headswim being fantastic on that run – I think it was ’98. And I was speaking to another artist about this, but it’s one of the strange vagaries of the industry that from the outside it looked like everything was great – there were TV spots and magazine spreads – it really looked like they were going to blow up.

Yeah, we did a fair bit of TV – we did TFI Friday. I remember doing that. And we did all the other ones – all the ones you would do in those days (I can’t remember the names of any of them now).

But, by the time we did that, we’d done a year in America, and a year in America for a band would galvanise you. By the time we got to England to do those shows, we were a well-oiled machine, and they were impressive shows, and it was a shock that it didn’t work really. But it’s what happened in those days. Sony had spent a lot of money, they had a bit of a clear out at Sony, and the accountants just looked at the books and dropped a bunch of bands who weren’t recouping, and it was bad for business. So, that’s what happened. And, I think by then, everyone in the band were a bit washed out with it all.

I think, recently, they said they were recording at Real World, and it stretched into infinity really.

Yeah, it took a long time. I remember going down to see them. There’s a B-side of Dead, like a stark version, which is fantastic. And it’s got a song called No Ticket, which was also great. They were in doing B-sides, but it took a long time, that.

They were at it for a good year or so, and there were no gigs. They didn’t do any, and then I went off on tour with someone, and by the time I came back, it was all gone. They were dropped, and that album never saw the light of day.

And it was good. It was good. Who knows, we might get to hear it. But… Dan’s done versions of some of those songs, and he prefers those versions and doesn’t want the old ones coming out. And then there’s some stuff on that album that has never been heard by anybody – that should come out. But we’ll see. We’ll see what happens.

Coming back to it after twenty-odd years, for you must have been a powerful thing; because the buzz around the show and the reissue of Flood… I almost feel like there was more buzz around the reissue than the original album – so, it must have been special coming back to this.

It was very special. It was one of the most special things in my career, I’d say. Probably the most special thing.

After twenty years, actually seeing them come back and, I didn’t work on Flood, and they didn’t do many songs – I think they only did Dead when I was working with them – so, I didn’t know those songs. I’d never really heard that album. So, it was… yeah. Getting down to mixing them was very exciting. It was almost like hearing a new album by a band that I loved, who hadn’t done anything for twenty years. And I got to do something with it.

And I got a lovely message on our group chat, after I finished it and band members were saying they liked it or loved it, and Dan said, “second best Headswim album ever made!” And I was like “wow! I can die happy!”

It meant a lot to me – I shed a tear during the gig, because it was emotional. And I think it was emotional for a lot of the audience. It was a really special night, I mean, it was really – some of those fans… I found out after the gig that some of those fans had been through things in their lives back in the 90s that Flood had helped them through, or they associated with it in a very significant way. So, yeah, there was a lot of emotion in the room, there was a lot of excitement.

It was the kind of… I’ve done a lot of gigs in my life, and there are certain times, like the first year of the Darkness, where there’s a certain sound to the cheering when a band walk on stage, and you don’t get it that often, but it was there that night. It was a really special night. My kids came. It was a big deal. It was a really big deal and something that I felt really fulfilled after having done. And I’m really grateful that I’d been available to do it, and that they’d asked me to do it. And that we got to make a record after. It was a massive thing.

Yeah. Massive.

Especially when you don’t ever think you’re going to see it happen. I didn’t think I’d even see them all in a room together at once. When I went to see them rehearse and they were in this tiny little rehearsal room – it was lovely just to see them all there and sitting around the table having a couple of beers like they used to back in the day. It was great, it’s a really major part of this part of my life – a massive part.

Well, thank you so much for that – it was such an interesting discussion. It’s been so interesting and getting into detail on the recording was so interesting.

Thanks for asking me.