Steve Chandra Savale, AKA Chandrasonic, is on a roll. As guitarist in the remarkably eclectic Asian Dub Foundation, he’s found himself, more often than not, fending off lazy accusations of political activism and all-too-rarely is he given a chance to talk about the magical musical chemistry of ADF. As a result, when I ask about the art-rock influences that I thought I’d picked out in his playing, the floodgates open and it is glorious!

A deeply passionate and knowledgeable musician, Steve practically fizzes over with enthusiasm as he discusses the band with which he’s spent the bulk of his musical career, and it’s obvious that his relationship with ADF is symbiotic, the band as much a part of his consciousness, as his undeniable influence is part of its wider make-up.

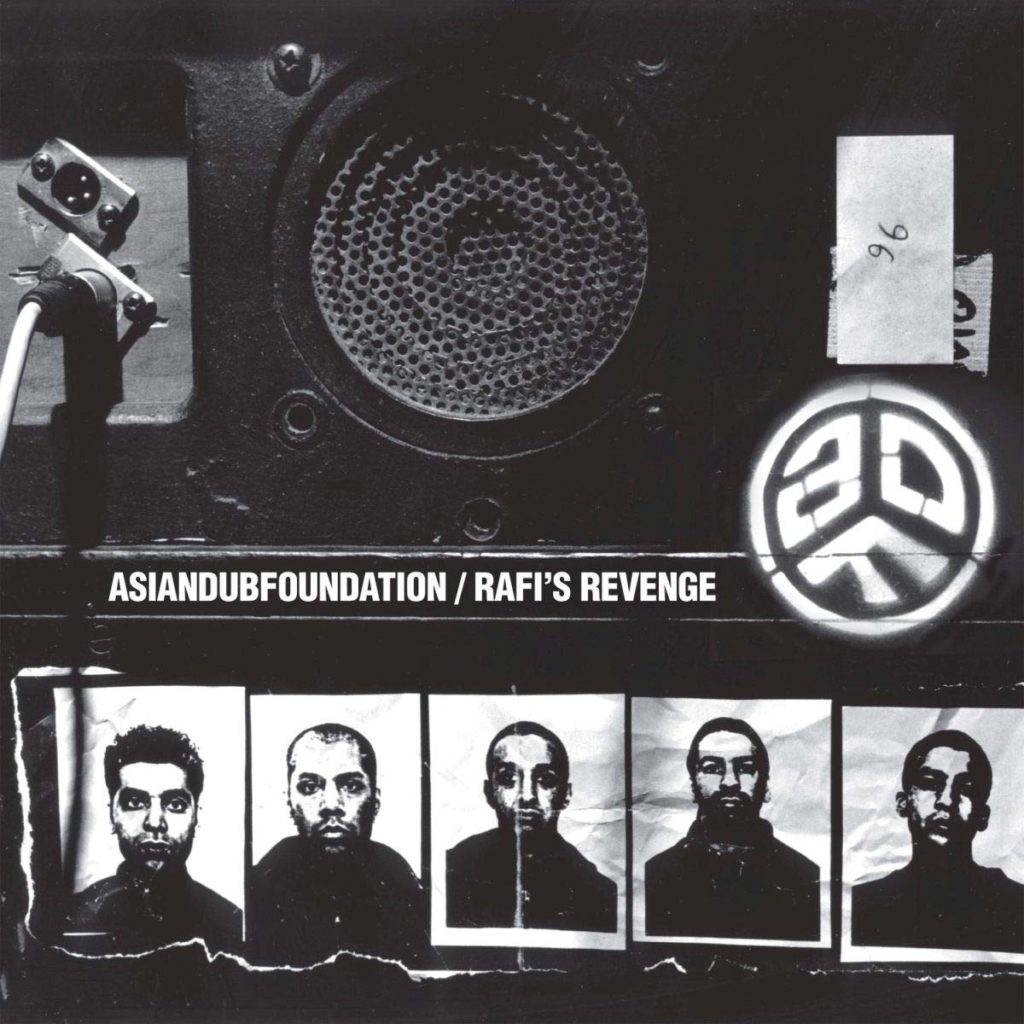

With the two-disc reissue of Rafi’s Revenge the nominal reason for our discussion, Steve does much to put both band and album into the context of the time in which they were created, as well as giving insight into the steady evolution of the band.

First of all, thank you for agreeing to talk to me, I really appreciate it.

That’s cool…

So, I mean really I wanted to start off by asking you a little bit about your guitar influences, because your playing is really unique and listening to some of the tracks on Rafi’s revenge, the influences to me sound like they come from a wide array of things from sonic youth through to jazz, so I was wondering if you could tell me a bit about how you started…

You should be careful! I could talk about Sonic Youth all day…

…At this point our house rabbit, who has already distinguished himself by chewing through the cable that connects the telephone to the recorder, starts loudly chewing on a piece of furniture in order to get some food… like the well-trained servant that I am, I obey before getting back to the interview…

One second, sorry! The rabbit is going nuts – he really is Pavlov’s rabbit… anyways, yeah, so – Sonic Youth…

Right, let’s see… because I very rarely get asked about this. I haven’t been asked about this for about 15 or 16 years, so there has been a lot brewing up!

I’ve learned as I’ve gone on; you know, after you’ve done this for so long, you start to realise what your real influences are. If you had asked me 20 years ago, I would have said:

“Oh yeah, Public Image Ltd and reggae and what have you…”

But, if I’m honest, I grew up with an English working-class mother and an Indian exile father and they’re both massive music nuts. The biggest influence in my house was classical Indian music and 50s rock ‘n’ roll. Now, that tells you a lot, right? In fact, that tells you everything about what I do. My parents’ first 2 dates in the 50s were Ravi Shankar at the Royal Festival Hall and Buddy Holly at the London Palladium, so that’s our starting point. In fact, that’s my starting point for everything now…

When you start playing in a band, you always think about your teenage years, but also, it’s your early stuff. You know, when I was 11 or 12, I started buying singles and it’s very interesting what singles I bought: ‘Space oddity’… the re-released ‘space oddity’ was number one. The bit that really fascinated me was the outro with all that crazy guitar noise – you know it was classic late 1960s “how do you make the guitar sound like it’s from outer space?” So, you know, you put a load of… what’s that echo – the one Syd Barrett used?

Oh, you mean the analogue tape echo? Those things are awesome…

Yeah, you put the tape echo on it right and then you scrape the strings that’s what the outro of ‘space oddity’ is. Also, they re-released ‘Itchycoo Park’ in mid-75/76 (or whenever this was) and I bought that as well because of the drums. Back when I was 11 or 12… I was a space freak – any record that had phasing or loads of echoes or space noises on, I was really into. It’s not dissimilar (and I’m not comparing myself at all) to Jimi Hendrix – one of the things that he used to do with his guitar was to impersonate the Flash Gordon films that he went to see at the cinema. So, when I got a guitar, I wanted the guitar to express the things going on in my head; I wanted that before I even learned to play. I wanted it to sound like space noise, yeah.

So, that’s my starting point really. Now, accidentally, the first influence really was The Who. In fact, it was my brother who was learning the guitar and I started to pick it up. At a jumble sale I got a book called ‘10 years of The Who’ and it had all the chords in it that I didn’t know, although I knew the song ‘Pinball Wizard’, I think.

I started listening to them for 2 reasons… because I had the book, and because I saw a documentary piece on TV. It was already 10 years after the fact, and I saw them smashing the guitars and I loved the sound that made! So, before I even played properly, I didn’t want to play properly! I wanted to make the noise. I wanted space and I wanted destruction and I wanted explosions! It was pure naked expressionism, you know.

So, it was all that and then of course punk and post-punk, particularly, was very good for that. You know, when all of a sudden you had these fantastic guitarists who thought the same way really. They were just using the guitar to express themselves, they weren’t being virtuosos. And there was that reggae influence (not reggae influence for me initially) on the bands. Yeah, Joy Division; Public Image, obviously, where the bass and drums are actually lead instruments and the guitar is colour… it’s colouring in the space around the bass and guitar. That influenced me a lot so, when I started to play in bands, I was already using the guitar with the idea of having the bass and drums as lead. You know, the bass is an important instrument – like Joy Division and The Stranglers even; it’s not about how the guitar influences you, it’s about how the guitar fits in with the other instruments.

So, yeah – there’s the post punk thing. Now, in the mid-to-late up until the late 80s, I was blown away by acid house and the whole ecstasy thing and there was a very interesting period where people were throwing guitars in the bin. People actually thought ‘this is gone’, and I was the same. I left my guitar by the radiator and the back melted! And I learned how to use drum machines and samplers and analogue synths and everything like that. And you know going out every weekend and dropping e’s and stuff. And, you know, this whole thing about the guitarist on stage… it’s a funny thing – the whole experience, because of the rise of the DJ kind of destroyed in a way; the superstar DJ. Initially the DJ was a servant of the people, and guitars and individuals forcing themselves on an ecstasy-created crowd psychologically doesn’t work. But the thing is, I got tired of that very quickly because I just thought I was doing the same thing every weekend and everyone was having the same conversation and listening to the same music, as interesting as it was for a time.

The other interesting thing with our sound, and that’s what’s kept me interested in guitars and bands, was because Adrian Sherwood was doing things to live bands – that electronic thing and it was shifting the sound and he was playing about with the music and using principles, which I got into as well.

Now, when Dr Das asked me to join ADF, I’d already been in a group with him called Headspace – which was a really good hybrid live band: bass, drum machine and electronics… but he wanted me to play guitar. Literally the first gig I bought my guitar to, we were supporting The Shaman and Orbital and, you know, Orbital were amazing right? And they were looking at me like: “what’s that doing there?” It was great really, but I realised then, because I was so into creating soundscapes, that I’m not being a virtuoso. My whole thing from then on… From when I joined Headspace, through to ADF… My whole thing with the guitar was to think how to help the rhythm on the drum and bass like “how do I help that? How do I make that interesting? How do I retain the aggression and the forcefulness that only guitars have?”

It’s only the guitar that has that kind of noise… that physical noise. And, also, I think… my theory on electric guitar… [catches himself]: See? I told you I’d go on about this!

My theory on electric guitar is far bigger than ADF and things like that. Actually, here’s a question for you, and I think you’ll probably find interesting: Why is it that Marshall amps were made in London in 1965? Why is it that Townshend and all them want those bigger amps that were, like, dwarfing the American music market? Why is American Music so quiet and wimpy and why was British music so ******* loud and aggressive? Why was it Hendrix had to come to London to do what he did? Have you got any answer to that? I’d like to hear it…

The only guess that I can make is the is that it was one of the Davies brothers from the Kinks, I think… he started shredding speaker cones to create that distorted sound…

Absolutely right, that’s the historical timeline, but I’m talking about the collective psyche…

I don’t know… um I can’t think why specifically it would be England…

Think big historical events it’s really ******* easy, man – I’m telling you! I have this thing… I’ve got this branch of pseudoscience, right? I call it social psychoacoustics. When were all these guys born?

Just before and during World War 2, I guess.

That’s the reason! What are you talking about? What was the biggest major collective experience in cities in the 1940s?

[Finally dawns on me, what he’s getting at] The blitz!

Bombs! Bombs – the Blitz! Explosions! Volume man! Even if they weren’t born, then they had parents who were. They played in bomb sites. The bomb is in the psychological collective unconsciousness of all the original rock people. Hendrix was able to develop it by coming to London to see the bomb sites. That’s why the electric guitar is so powerful and still is today – because it was forged… it’s a kind of response to; it’s an infant’s response to that huge psychological kind of trauma.

Rock music, and I mean rock as opposed to 50’s rock ‘n’ roll; the Afro-American R&B… it’s the British response, and it is a response, to trauma. I read Pete Townsend saying that this was the way that they could compete with the modern world – by having loud amps and things like that. And all they talk about is playing with bombs amongst bomb sites and things like that. I think that this really is the source of it. My mother talked about how she experienced the ‘doodle bugs’ – those terrible flying bombs, so I had it as well. You know, it’s war!

That makes really good sense. If you look at the bands from Birmingham like Godflesh; Black Sabbath before them… Napalm Death… all these bands developed in response to the society that emerged in that post-war landscape.

Yeah, it’s no accident that Birmingham had that kind of pure heavy metal. Birmingham is the worst of it all really! Yeah, I think that’s a big thing. So, if you ask me about my guitar influence, you’re going to get a whole ******* book mate, you know what I mean?!?

The next stage, right, well that’s why I think the guitar endures. I think maybe it’s at the end now, but that’s why it’s endured for so long.

For me the next stage after that is loving electronic music. Just loving deep bass music and being absolutely blown away by jungle. Not drum ‘n’ bass – jungle. It was, for me, the last gasp of what happened in the 50s – that Afro-American R&B – then punk with distortion – free jazz, even… which is really exciting music! I’m surprised that people didn’t see that more – the original jungle music was really the last breath of rock ‘n’ roll, or whatever you want to call it. To me, when I heard jungle it had everything in it – it had the reggae, it had the high-speed punk energy, it had free jazz… wild free jazz before all the pretentious free jazz – and it was just really instinctive. It had youth and it was also the first music that I notice had this young generation of Asians really responding to it equally in the inner city to the young black youths and the interested white youths.

I was working as a kind of youth worker / teacher (like the other members of ADF), so my task with ADF was to have a guitar that retained what was great about the guitar the sound and everything like that… And to make it work with drum ‘n’ bass and jungle and electronica. You know, people actually compared us to Rage Against the Machine, and I didn’t like that because I didn’t like them so much when I first heard them. I just thought they sounded like some Led Zeppelin thing with a bit of rap, but Tom Morello came from a different plane and he came to the same conclusion, which is that what you’ve got to do is you’ve got to get rid of the virtuosity. Well, I never had it anyway, but he probably does, and you’ve got to sublimate the guitar to the overall form of the music.

The problem is that people started putting guitars over sampled beats and breaks and stuff like that, but they still have this idea that guitars have to be first in the songs, and that’s why you got indie-dance and there’s only one way you can really do that – So, you got that Happy Mondays sound and everyone pretty much sounded the same. Primal Scream were probably the only ones who went a bit further than that; whereas with Tom Morello it’s hip hop. It’s hip hop and he was doing breaks and scratches with his guitar. He was making the guitar fit in with the style of music. So, he could go to the Zeppelin riffs, but then he could stick in this scratching and this whole barrage of effects and he did it so that it basically works with heavy metal and what have you. And I wasn’t a fan when they started comparing us to them – I hadn’t even listened to it. I had heard one track and I didn’t like it – that’s the honest truth; but, we kind of use the same psychological methods.

Anyway, so I started playing to very fast tempos jungle break beats and, basically, I found that I would just dampen the strings and use a wah pedal – no notes. On the first album there’s a track called ‘PKNB’ and what was wonderful was that, playing it, there a group of youths in their teens and they’d heard nothing but jungle. So, they asked me to play a bit of reggae guitar and I played it; and then they said: ‘play jungle guitar’. And I realised that they’d seen me play it and thought that that’s what you did on guitar with jungle! As far as I’m concerned, I was the only person in Britain attempting to play a distorted, punky, post-punk guitar along with jungle… And I put the challenge down to anybody: if you can find any record before 1995 with live bass and that style of guitar over jungle break beats. You will not find it, because it wasn’t there. There were lots of people who started using live bands with what became drum ‘n’ bass, which is a different kind of music… and it was good stuff – like Roni Size and things like that. It was live bands, but it was more jazz oriented… more from a Miles Davis kind of school whereas ours was from real, raw, reggae and punk style. It was quite forceful and in-your-face, and it was on ‘Rafi’s Revenge’ that we really bought that to the fore… [catches breath for a moment] Does that answer your question?

Yeah it does. I mean, I’m more from a rock background generally anyway….

I’ve done all! I can talk to you about any rock from the late 60s through to the 80s…

…but I grew up and I started exploring all this stuff. I was a teenager when ADF came out, and I think you guys played Reading Festival and I saw you there, and bands like Massive Attack and Orbital… Actually, I think orbital might have been the first non-rock band that I saw live and they scared the **** out of us with ‘Satan’!

They were amazing! They were a great live act. The first gig I did with Dr Das was with orbital, and I’d never seen them, but I had heard them. They’d just got chime in the charts and I was going: “wow this is amazing!” I just realised after the gig that I was watching these 2 bald guys looking at each other over a pair of office desks and I couldn’t decide why it was so good! But I think it was because of the tension. They were playing it live and no one else was doing that back then. They were a live band and they went for it, and they said that they were as good as any other live band out there, and they were. They were like a great rock ‘n’ roll, punk band and they had electronics and that was very important for me. As well there was this false opposition between the line ups and formats. It’s all about that exchange; that tension; that need to get stuff out. It doesn’t matter what you use. Sometimes I think the DJ format is against that, but sometimes even a DJ and MC can have that exchange and tension between each other. They’ve developed it and that can be great live as well. Rarely… but it can be.

When you joined ADF was it the case that you were the primary writer in those early days?

No, I wasn’t. No, that’s not true. The first album was mainly Dr Das and Master D, the vocalist. Pandit G, the DJ, did a lot of stuff as well. No, I was never really the primary writer. But, from the fourth album, there were quite a few tracks that I wrote most of. And then Dr Das would have amassed things like the one with Sinead O’Connor (‘1000 mirrors’) and ‘Fortress Europe’. On the first three albums there was a very good balance. A very good balance definitely… you know, the four of us would do lyrics. On the third album we would literally sit, the 5 of us, and we’d sit with a blank piece of paper and come up with stuff. The first three albums were genuinely balanced; very collective.

The first track I suppose I did mainly by myself was a track called ‘box’, or at least I did most of the preparation by myself. I by no means did the performance, but it was a track called ‘box’ and it’s the last track on the first album, then on the second one and the third album I think… yeah there was a lot of really good collective writing.

When you got involved, you mentioned that you got really into synthesis and drum machines and stuff… that must have given you a very good background to get involved in the whole kinda conceptualisation of the band’s sound?

Yeah, that’s true. Yeah, for sure – that’s absolutely right. But then I’ve always been like that. I was like that before I could do any of it. It was always about: “what is this about?” It was about expressing yourself. I never actually aspired to be a musician. My first aspiration was to be a science fiction writer, but I found it very it was much easier to get the vibe that I was getting in stories across with guitar and electronica. So yeah, what’s that word… synaesthesia – where you mix up your senses – I’m like that artistically. I can’t really see a difference between films, books and music. I don’t really see a difference. Only in the methods… in the hardware. Artistically, I see no difference between those different forms. I feel no difference. So, it’s always been like that for me, that’s why I’ve never been a virtuoso. That’s why I’ve never aspired to be a great guitarist. I’ve tried occasionally, but I can’t be bothered. I just have an idea that I want a song to sound a certain way and I want to do something about it – “How do I represent the idea using the tools I have?” That’s the only way I work – I think I’m condemned or blessed!

The reason I asked about Sonic Youth was mainly because they were a huge influence on me and one of the big influences was when I opened the CD booklet on ‘Sister’, I think, and inside they had all the tunings written out…

…It’s Philip K Dick who was my big science fiction influence – that album. It won the Philip K Dick society award and rightly so.

…because you experimented with a lot of tunings, right?

Loads! And they were a big influence. They were a massive influence. They were fantastic. My gosh! ‘Evol’ was the one that really got me – it had things like ‘expressway to yr skull’ and ‘star power’.

In a way, they throw away all the conventions of guitar playing and that’s what I really like. You know, you can do so much with it… I mean it’s amazing that no one had really done that before to such an extent. It’s quite an obvious idea really, isn’t it? I suppose what it did mean is that, the last time I saw them, and I saw them many times – they had 40 guitars on the road. They had like 20 guitars and 20 backups and that’s the only problem with doing things like that: because each song is based around a guitar. And I love that idea. And it could be any guitar. It could be a guitar that doesn’t work properly; it could be a guitar with like 3 strings or the neck hanging off; but if it makes a sound and inspires you then it’s great and I love that approach to guitar, because I really can’t stand guitar-ism. I’m not interested in the make, or if it’s some 50s Les Paul.

There is, if you look online, Chandrasonic’s top tips – and that was very flippant. A guitar magazine asked for it and they got complaints about it, because basically I said: “don’t use Les Paul, use cheap Japanese copies!” and things like that. The guitar, as an instrument, is strangled by its own history. That’s something that I used to say with ADF. My whole idea was to throw out anything other than aggression, noise and rhythm. You know, rhythm. A lot of the time I would try and play like a drum especially with things like jungle and reggae – basically the guitar I’m playing is a rhythmic feature. So, I would think about that a lot and I would think about making the guitar work as a rhythm sound. Not even musical, you know. Unfortunately, a lot of guitarists, when they pick up a guitar, play something that they think they ought to play on guitar. But, right from an early age, I had the idea of not doing that. I wanted to play something that hadn’t been heard before, and I think that’s the only approach really. Now I think it’s even worse, in a way, because with YouTube and things like that you can learn every aspect of the guitar that has ever been really. You shouldn’t watch anything! You should just pick the thing up, not even knowing what it is. When I was doing that documentary for Aljazeera, I was in a village in Mozambique and this guy had a three-string acoustic guitar and a load of girl dancers and he was like [imitates screaming incoherently] and he was singing like that and playing the guitar completely out of tune… but it was brilliant. It’s one of the most original things I’ve ever heard. And, you know, he’s in a village where there’s no electricity, there’s no toilets; and he just got this instrument and he needed to express himself. And it was glorious because there was nothing for him to take from. It was pure, unadulterated… he didn’t know his guitar was out of tune; he didn’t know that it only had 3 strings or that it was supposed to be something else… and he just shouted because he was so hoarse. He was about 13 and he had all these girls dancing in step. It was weird, but to me he’s a better guitarist than Eric Clapton… For me. This young guy playing a battered acoustic guitar player in some village in Mozambique with no electricity and he’s the best guitarist because he’s never heard *** ***** like Eric Clapton and he hasn’t had millions of YouTube videos telling him that this is the way you do something or that this is what 60s casualty so and so does on this song… It’s a problem, I think, especially with guitar. There’s almost too much history.

Which kinda leads me onto one of the other things I really wanted to ask about, which is where ADF moved into film scoring…

We’re in the midst of one of them now…

…Because for the evolution of the band’s sound, working off the cuff like that… particularly for things like thx 1138, which is so dissonant and dark… that must have really pushed you guys to go beyond what you know. In particular beyond the album format, which can be quite regimented…

Yes, that’s right. In fact, the first one we did with ‘la haine’ in 2001 – we learned exactly what you just said. Even a band like ours, when we thought we weren’t being regimented – you start to realise how regimented it is. There’s nothing wrong with regimentation. You know, minimalism and repetition are good, but you can’t do that as such. It’s like the film is a dictator – it’s almost like the lead vocalist, especially if there’s dialogue. So, you have to respond to it, because it’s really obvious when it doesn’t work. So, you have to do like different numbers of bars; you have to pull yourself back with something like THX more than anything else. We used a lot of techniques which we’d never used before; like all of a sudden, I’m suddenly playing on my own and things like that… We never do that at an ADF show, where there’s just one sound every 30 seconds or something. It is a really, really interesting thing to do, but it’s very challenging, and I think we’ve had a good success rate.

‘La haine’ we’re still doing. Pretty much musically we are playing it much better. We’ve got a great drummer now, but we’re still playing basically the same score as we did in 2001, and we’re still getting sell out shows some 10 years later. It’s something that’s pretty unchanged and we did ‘Battle of Algiers’ which is an amazing film if you’ve never seen it. It’s a very important film, I think, and we did that twice in 2004 and we’re doing it again now.

It’s difficult man. The problem isn’t the playing, it’s the technical side of marrying the film itself to the music; what formats you can use; sound; film speed and all this kind of stuff. I just sorted out… I’ve literally just finished, so if you’d done this interview yesterday you would have seen huge bags under my eyes. I would have been [makes wailing crying sound], so you caught me at the right time. I’ve solved a lot of problems, so I’m in a great mood now. It’s quite a challenge to go out of the band format and try to do something where there is no model. Most of the groups that do it, do silent films, which to me is a cop out, having done these ones with dialogue. But I think the fact that we’ve done ‘Le haine’ and we’re still doing it and we’re still selling out shows is a testament to the fact that it does work and, as a band, it fits with one aspect of what we do.

So, working through that, did you find that it opened up new possibilities for the albums that you produced?

Yes, it did. In a lot of ‘Enemy of the Enemy’ (OK, it’s not that recent, that’s 2003) a lot of the ideas from that… well a few of the ideas that went into the album came from ‘Battle of Algiers. A lot of ideas went into the album afterwards and a lot of THX went into ‘signal to noise’. Yep, it’s a good way of writing.

It is really interesting, because I kinda like any band that goes beyond the norm in whatever way that maybe. It’s always interesting to hear bands that step outside of comfort zones and I love the idea of doing something like that. It’s just a great way to combine the visual elements of the films and riff off someone else’s emotional backdrop…

When I think about it, it’s probably… I don’t know, it might sound a bit big headed, but I think we are quite an innovative band. And I think this is perhaps the most innovative thing we’ve done, and it had some repercussions. when Fabien (Riggall) from Secret Cinema… Or he went on to found Secret Cinema… he came out to see us do ‘la haine’ and he rang me up and he was chasing me for a while because they were doing ‘Battle of Algiers’ and I didn’t want to answer his calls because I was ****** off because I didn’t want to see it unless I was doing it. But eventually he came and told me that one of the influences that started Secret Cinema was him seeing us do ‘La haine’ at the Barbican in 2001. So, it is a legacy thing and I’m really, really proud of that. It was quite unusual, it was a bit dangerous and it hasn’t really been done before we did it for ‘La Haine’ and it went onto something else in a different medium that was very cutting edge. The whole Secret Cinema thing, which is now massive, and him and his crew (you know, I’ve been to some amazing events) and the fact that what we had done had some influence on that – I’m very proud of that I must say.

Thinking about the time that ‘Rafi’s revenge’ was released… You know, 1998 was a very odd kind of time, I think, both socially and musically. It was kind of that post-Brit pop, post-Labour-euphoria hangover and, as we emerged there were bands like Massive Attack putting out ‘Mezzanine’ and both your album and theirs, are significant and, I think in slightly different ways, prescient of the storm clouds that were already starting to gather socially.

And I know that you’re not overly keen to be seen as a as a political band, but you did say that it was important for an artist to tell the truth, and I thought that was a very interesting way of putting it and wondered how you feel the socio-political element fed into the album?

That’s a very interesting question, looking back on it, because almost now I look back on that as a much better time! I’m not nostalgic at all, but the Iraq war was such a nightmare. It’s the worst thing that I can imagine that happened in my lifetime in terms of governments being complicit in what was a mass murder for no reason. That had a big effect. I mean, you say storm clouds gathering in 1998 but I think, well, in some ways we weren’t doing that badly compared to where it went. We were moaning and complaining and shouting, but we were… you know that energy that came from us coming together and we realised we could say something about our experiences. Because no one at that time… I mean we weren’t the only ones, there was a big bunch of us, but I think we had a very distinctive musical approach.

And, remember, this is the first time there’d been an articulation of second and third generation Asians. And, you know, that’s why we had the name. And that’s a very problematic term and it’s became increasingly problematic. You wouldn’t call your band Asian Dub Foundation now, no way, but at the time we chose that name… Well, John chose the name – it was just for a local Tower Hamlets benefit gig and it was to do with getting young Asian people involved in music protesting against the BNP, who were very strong in the early 90s (people forget that). So, we were coming at it with that anger and opposition and it was a very local, Grassroots sort of thing. But, the historical experience of being a minority and being treated like that; I mean growing up in the 70s in Britain – it is hard to describe how awful it was, in so many ways, for Asians – no matter what their background. And we all have very different backgrounds, and we’re all different ages. Deeder, our singer, he was 15; I was already in my mid-twenties. And he was a Bangladeshi, or son of Bangladeshi immigrants, who lived in East London; I was a mixed person – son of an electrician from Hyderabad living in west London; and Dr Das was very different; and John Pandit – he was completely different again, as was Sanjit.

We had all different religions in the band, you know… And I’m actually brought up an atheist. A very forgotten tradition is Indian atheism – scepticism actually. And so, one thing we all had in common which we really hated was people… you know, people who see a Brown skin and say “Oh you’re this…” I think when people saw us, they were quite shocked (and people who liked us were pleasantly shocked). We really did have people come up to us and say “I wasn’t expecting that! Where are your Sikh outfits? Where’s your lovely dancing? It’s not like when I went to Goa! Where’s the Shiva?”

And we had people with beads coming up to us and hippy stuff, and we really hated that so much. Listen: Indian history is really violent. Its violence and revolutionaries. Gandhi has been massively overstated because it lets the British Empire off the hook. Gandhi was a pretty unpleasant individual and he became more and more known. So, it’s either Gandhi Hollywood or hippy, you know what I mean? Or it’s a Paki, so let’s push shit through the door… You know there was nothing… there is no overall, honest, holistic representation of these millions of Brown people in your midst. So, we were brought up with that; all of us to different degrees; and we wanted to let off and we bought all our musical backgrounds. We let everything in. Reggae, obviously, the dub bass which transferred to jungle and we had all this other stuff as well. You know, I was psychedelic rock ‘n’ roll, post-punk and then experimental music as well industrial music like Adrian Sherwood and early 80s Cabaret Voltaire type stuff… The three of us were aware of that kind of stuff; that electronic stuff; there’s all kinds of things in there. But then, we also had a 15-year-old who only really knew jungle traditional Bangla music – so we had to make it so he liked it and wanted to sing with it. It was great, and that was the base sound. It was a massive, disciplined cacophony with loads of influences and, consequently, it sounded unique, but it also sounded very ‘of then’. It could not have happened… ADF could not have happened before then. It would have been musically and generationally impossible for us to have happened before that period. So, when you look back, you see the politics of it. I can’t separate that from the music, and I don’t think I ever did. This is one thing that people got wrong about us. They overemphasise the politics and didn’t understand that, if there was politics, it comes from the music. Its musical politics, its inseparable. But unfortunately, the press tended to separate it. So, you know, questions like: “are you activists or musicians? Are you this or that? Are you either or are you or?”

And that was unfortunately the way that a lot of the less thoughtful journalists tended to look at it. Whereas, it’s funny, because the older journalists from the previous generation… they basically wrote the best stuff about us. People like Charles Shaar Murray, Nigel Williamson and all those people. You know, people who now write lots of books and run rock’s back pages and stuff like that. They wrote great stuff about us!

My musical education was very much throughout the 90s and I think it was an innovative time…

It was when you look back on it, wasn’t it? You had jungle, trip-hop… you can reel off a whole load of types. Britpop was like a kind of conservative reaction against it.

Yeah some of that was kind of horrible…

It was really, really bad! I still maintain that it was one of the worst things to happen to British music!

It felt to me, growing up through that period… you know – bands like Massive Attack and Dreadzone – it felt like there was a real opening up and that a community was emerging where you could listen to heavy metal and you could listen to ambient and you could listen to all at once if you wanted…

Yeah, that’s true. Yeah, you’re right you know…

…and then it seemed to get compartmentalised again.

Yeah, it is a bit like that too I suppose…

…but, you know, we were told that the internet was going to open up new vistas. But it just seemed to result in things being put into ever smaller boxes…

Yeah. That’s a great point actually and that’s seen in the bands they always talk about if you want to read music press now (and I don’t very often). If you’re in a band, the ones that are successful are the ones that fit in… like, the middle ground, you know? I don’t want to knock them, but the 2 Door Cinema Club and the 1975… they seem to have a lot of bits from things that are inoffensive and then they have a sort of knowing cleverness about it. And that’s what gets you the brownie points. It’s got to be accessible, middle of the road with a knowing wink. I don’t know if you’d agree with me, but that seems to be the way for bands anyway.

Yeah, I get an awful lot of great music… but the best bands that I seem to get generally have about 10 followers on Facebook and it’s disheartening but, you know, they’re usually the best ones.

Well, you know, you can have your own micro universe and that’s the thing that’s going on with the music scene. We were at the very tail end and you know you were listening to us and the other things that you were listening to… and for us, being an active working band – we were at the end of a system that had probably come about in the late 60s when Bands actually started to get paid for their recordings and when the album started to become a currency… And they were a kind of semi-intellectual, but not really (and thankfully not intellectual) area of popular music that was between pop and classical music or opera or whatever – in between those things and in between pop disposability – and it was always shifting one way or another, but there was no centre except what was represented by the music press; by John Peel… do you see what I mean, there were like these centres of authority and there weren’t many of them.

I remember reading that Joy Division were going to be on TV and just salivating for a week and getting ready for those arguments with my parents – “I must watch this programme… Oh no! It clashes with Coronation Street, what am I going to do?!” You know what I mean? It’s like the centres of where it happened were very small. But with Napster… I suppose everything changed the moment Napster emerged and music then became free to exchange.

And it’s interesting what you’re saying about what people think. People thought the internet would be this great liberating force but, weirdly, it pushes everything back to the middle because it’s so diverse. If you’re going to make any money off it, you’ve got to go to the centre ground. It’s like America really, you always wonder… you probably wondered… why the majority (and you know that early grunge scene was a big exception), but why the majority of the most successful bands in America were the most middle of the road ones, and the reason for that is because you’ve got to appeal to fifty different States. And I think the internet is like the US middle ground on an infinite, global scale. That’s why a lot of music is right in the middle.

I mean, I watched Top of the Pops at Christmas, and I really hate myself for saying this (I was always going to be open… I was never going to say “it was better in the old days”) but literally every act had the same vocal sound. Every female act that you hear on the average pop radio sounds like auto-tuned Rhianna. There’s one setting and British pop has about three or four producers who do it all? That’s the complete opposite of what the internet was supposed to be about…

But, then again, you’re only talking about that kind of mass, popular culture centre. The thing is that, around that now, around that periphery, there is an infinite number of micro-universes that can be self-sustaining. It has some weird effects. Don’t get me wrong – to give you an example I’m not making some inter-sectional point- but our sound man was doing a reggae festival in Peckham and, you know, Peckham has a large Jamaican community. So, it was a reggae festival in the centre of Peckham, in a big park, just off the main drag. There’re no black people there! Is that bizarre or what? It’s because this particular reggae festival has its own Facebook page and things like that and it’s quite old school. There are some good acts on there, it’s a nice vibe! But that is what can happen now. You can have a reggae festival in Peckham and there are no black faces in the audience and, believe me, I’m not making some kind of… that’s juts an example, I don’t want you to think I’m some lunatic… agh “everything’s racist” … I’m not like that at all, but it’s an example of the kind of micro-world that can create contradictions like that… it’s because of the internet.

I’ve only really got one question left – putting together a special edition of an album like Rafi’s Revenge, how involved did the band get with putting this together? Is this something that ADF were keen to do or was it more of a label thing?

I wouldn’t say it’s a label thing. The current members have been doing it for so long that everyone has a very different perspective to everybody else. You’re only getting one side of this from me. If you listen to John Pandit or Dr Das, who are still involved from the time; three out of five still there after twenty-one years is not bad going these days, so, you’ll get different stories from me… very different stories, I think.

We’re all very proud to have this out again and to have someone like yourself talking about it. I wasn’t… I have no idea… to be honest, I keep away from the mechanical side of the music promotion as much as possible. I love doing interviews but, you want to ask me about type set or whatever I don’t want to know. So, in that sense, I wouldn’t have anything to do with the label side of it, but in terms of what’s asked of me, yeah, 110% you know. Want me to talk about it, want to ask me about certain tracks that I can find…. Absolutely I’m very proud of it. It’s a really, really cool sounding record. I think there are some aspects of it that are actually easier for people to listen to than it was in 1998.

We united a lot of people… like yourself, who’s more of a rock fan – who’d come to us and stuff, which is amazing!! I’m so proud of that, I almost wish that I’d embraced that a lot more at the time. You’d get people saying to me “wow, I’ve never heard anything with drum ‘n’ bass or jungle beats or reggae…” and then you’d get the opposite. You’d get the people who’d heard of us a as hardcore, raw jungle act… because a lot of people thought we were; but we were in many ways, but we had bass and guitar and they’d never seen anybody who wasn’t a DJ playing this kind of music. So, it’s a wonderful thing and it’s got that and I’m very proud of it. Also, the vocals, I think, are a lot easier to digest. The more of the indie / rock people who came who’d never heard a vocalist [imitates ADF vocals on speed] in that style. Now, after ten years of grime, it’s pretty normal speed. So, I’m really happy about that because I think it’s a lot more digestible for certain sections of the audience than it was…

It was very different, I think, but remembering back to that time, there were a lot of cool acts breaking down and blurring boundaries – there was you guys, Massive Attack, Leftfield, Orbital (whom you mentioned) and then Senser more on the metal side… I loved all that stuff and I’m so glad I got to grow up at a time when that stuff was uniting audiences, because you never knew who you’d see at one of those shows…

Another thing about it is that we all said we were uniting audiences as well. We were all kind of fired up about doing that, and that’s a good thing as well. We were really fired up about pulling people together. Music brings people together, it’s all connected – thing like that. We were fighting formats and I suppose you could say that it’s harder now because, in a way, you get micro-formats now. I mean I teach a module at the place where we started – community music – I teach a music history module as part of a larger course. And I talk about all the things that I’ve been talking to you about. All those things – social science, the beginning of WWII. I teach that in my class and it’s like, when I hear what a lot of them are into, they come in and they say they’re really into this House music from this particular club and this particular DJ and it’s no different from any other house music at all! But of course, they think it’s radically different to this because they use this type of Hi-hat sound… These worlds are so minute now and the differentiation is so kind of sub-atomic particle level. And it’s almost the opposite of what was going on in the 90s. Having said that, I think people are genuinely open to all kinds of things in a way that they weren’t – a diversity of sounds. But in terms of what they follow and consume – it’s the opposite.

I suppose one thing about us that I haven’t mentioned is the international thing. Our sister bands were usually bands from Brazil or Siberia. Our starting point was Indian stuff from our parents, and Bangladeshi stuff, but we slammed loads of stuff on top of it, so we were interested in live bands with the same approach. So, groups from Brazil – they bunged all this other stuff like drum ‘n’ bass on top, or this group from Siberia who had all this throat singing stuff and then they added this weird, Nick Cave kind of vibe to it. And still, where I am now, that kind of stuff is still the most interesting when you hear bands from South Africa or guitar bands from Mali, I don’t know if you’ve ever checked that stuff out…

I haven’t… a lot of cool bands from Eastern Europe though…

Yeah! There’s a lot of Bulgarian stuff that’s notoriously complicated. Really you should check out Tinariwen and Songhoy blues – that’s the stuff I’ve enjoyed most over the last decade. Literally desert music and I tell you what, if you’re interested in the history of it – probably the real roots of rock music. People think that blues, imported from West African slaves, right? That was the original thing, but then no one could work out why traditional West African music sounded nothing like blues, and I think that it was more complicated than that.

The West African people of the time would collect slaves from the North-West – from Sudan, from Mali and they would be the ones that were transferred to the United States and the Caribbean. Not the West Africans, or the Ghanaians but they were more likely to be Malian or Sudanese and they bought the blues, and if you listen to Tinariwen or Songhoy blues, they’re playing a pre-blues, or the music that became the blues. It all became the version of the blues that became exported to America. So, what’s fascinating, it sounds so fresh, and you’re talking about 2008, you go to a market and all the music they listen to, it’s all electric guitar music and sounds fucking brilliant. It’s all bands – it’s guitar, bass and drums… there’s a scene there. Some days they don’t have water. When I got there, they had no petrol for two weeks and they’re all talking guitars, band rivalries… it’s like being in college! It’s like being in college, but you’re in the middle of the desert and water is in short supply! They’ve got electric guitars with portable amps and batteries and they’re making music that is pre-blues; music that is five hundred years before rock music! That’s where it all comes from, but it’s fresh because it’s young people in North-West Africa playing this music that their grandparents before it got exported to the West. You want rock ‘n’ roll man – check it out!