I still remember when Asian Dub Foundation emerged, back in the early 90s. As a fan of indie, punk, and metal, I simply wasn’t prepared for the remarkable sound clash the band were able to unleash, and my initial fascination was cemented by a gritty performance at Reading Festival in 1998.

Beyond the music, which seems remarkably timeless in its appeal, the thing that made, and makes, ADF special is their ability to not just sing about unity but to actively encourage it. With an overarching message of inclusivity, anyone is welcome at an Asian Dub Foundation show and, for all the interesting places their varied career has taken them, they’ve never forgotten their Community Roots, – as blazing new track Broken Britain clearly shows.

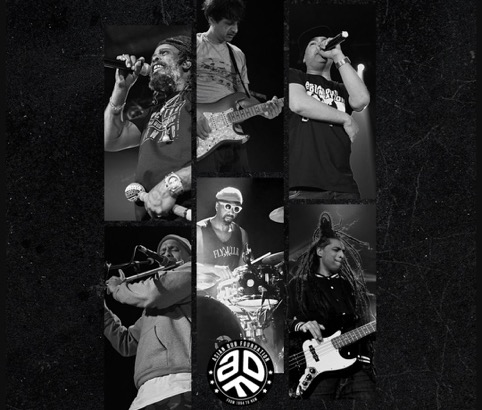

With the band celebrating thirty years, it was my pleasure to catch up with Steve “Chandrasonic” Savale to discuss the band’s enduring legacy. Steve in person reflects Chandrasonic the guitar player. An effervescent interviewee, he runs with any given question, often taking it off on fascinating tangents and, in many cases, all the interviewer can do is to wind him up and watch him go.

Self-effacing, but aware of the Asian Dub Foundation’s legacy and importance, Steve frequently allows his sense of humour to disarm weighty subjects, offering up incisive commentary on the state of things without feeling the need to preach. It means the time flies by and, before we know it, we’ve chalked up over an hour.

Join us, as we dig into the history of a band that remains one of the most crucial acts on the UK scene.

Yeah, thirty years. Insane really, isn’t it? I tell you what. At an early band meeting, six months into it, Dr Das said “right, we’ve all got to face it, this has about six months left to run…” Classic rock ‘n’ roll stuff! [Laughs]

And yet here you are. It’s interesting to see the band’s development because, right from the start, as an entity ADF were a very creative, cross-pollinating experience and you’ve consistently pushed into new areas with film soundtracks and collaborations. So, I guess one of the first things to comment on is how the evolution of the band reflects your own evolution as artists.

I guess so. It’s a creative impatience, I guess. The reason I came up with the La Heine thing originally, was that I’d just gone to see a guy called Scanner doing a crazy, absolutely lunatic, live soundtrack to a Jean Luc Goddard film at the Imax. It was kind of a disaster, but I thought it was brilliant. The audience wanted their money back!

Anyway, we were supposed to be doing something at a festival called Only Connect, and they wanted us to do something with a classical composer, but we didn’t like the idea at all. But I’d just come out of that Scanner thing, so I said, “let’s do a live soundtrack – what film would work?”

The answer was La Heine – and that was it.

We had no idea how to do it. I think everyone was wanting to kill me at one point! [Laughs] But we literally put the film up with our little sequencers and we wrote the music for it, and we’re still doing it twenty-three years later. Not really much has changed.

I think for me, I was actually annoyed at not being asked to do any soundtracks. Because we haven’t really done much film work and we should be doing it. So, that stuff – La Heine, Battle of Algiers, and THX 1138 – that was us doing soundtracks, but only to films that had already been made, live on stage. So, that was the impetus.

I think a lot of ADF changes, and development, and ideas, was feeling like we weren’t allowed to do certain things, you know. That whole thing about going against stereotypes of Asian people either being hippies or, you know, Bollywood film stuff. Which is great, but there are other aspects to our identity as we saw it then. I think it’s all to do with pushing against that. And, of course, it all goes into larger issues – immigration, racism… politics, you know.

Going back to what you said about seeing Scanner do the initial one – it’s really important, I think, to creativity – that sense that you’re teetering on the edge of not only acceptability but also your own ability…

Oh man! [Laughs] We didn’t know about frame speed. We did all the music with the band and we were really happy with it. And we’d done it to DVD, which is 25 frames per second… none of knew that!

So, when we got to the Barbican, we noticed that all our music was finishing too quick, right, because they’d hired in 24mm film stock, and we didn’t know. And I said to the guy “look, everything’s finishing too quickly” and he sped it up a bit. So, he turned the FPS up to 25… and we were panicking, but it worked!

But yeah, I had no idea about frames per second, so what you just said is absolutely more apt than you think, Phil.

It seems, particularly for you – because you were always experimenting and playing with tunings…and, of course, when you’re using different tunings, you have to learn a whole new way of playing, so I guess it’s kind of personified your career throughout.

Well, the retuning stuff was a mixture of two things, really. Being brought up with Indian classical music, the first thing I did was find every note that played E, so you just hit it and let it go. And I would sit there, and still to this day, I’m happy to play a guitar where all the strings are tuned to the same note. I’ll do it for hours. Someone has to stop me, you know?

It really is a sense of being brought up with the drone. And that took me to other musical places. Not the obvious Beatles’ stuff. But Velvet Underground – Heroin. That’s one of the best incorporations of non-Western drone music. Her drumming even sounds like it fits – no one notices that because it’s aggressive, it’s New York–street, it’s about heroin, and the lyrics are dark. But, you know, there’s something there for me. Rather than going to India and doing the guru thing and dressing up and all that stuff, what the Velvet Underground did (and the Doors with The End as well); they brought that music to where they were. So, the Velvet Underground had that very Indian classical vibe on Heroin (for me, anyway), but they brought it into New York – the street, decadence, and darkness. And that’s kind of what we did with ADF We brought our influences – Indian, Bangladeshi, the Indian sub-continent, South Asian influences – to where we were. And, once you do that, you can let all this other stuff like jungle, leftfield rock, dub reggae of course. And it all fits because we all know it, equally.

That kind of idea of bringing people together through music, and bringing disparate elements together – that’s a big part of teaching music history and bridging that divide, right?

Oh man, yeah. That is so important to me. Because we started in Community Music, and we were music technology tutors. Deeder and Aktar – the vocalists in the band, were in our workshops.

And, basically, I was an expert on midi cabling. What on earth use was that? [laughs] My teaching knowledge, as a music technology tutor, basically got deskilled very quickly.

Then they asked me to come back and do something, and there was a course called The Roots of Contemporary Music. So, I took the title, wrote the course myself, and it’s been an absolute joy. Unfortunately, it seems to have finished now. That was basically talking about the common roots of music. I think a lot of people don’t know that things like rock, soul and reggae essentially have the same root. In fact, you can even pull it down to a couple of artists and a couple of records- Fats Domino, basically.

Fats Domino is a common root to rock, soul, and reggae, things like that. And it was a wonderful thing to do, and it was great to play like real hip-hop serious aficionados like funkadelic and parliament, and then you’d play them stuff that Dr Dre and Snoop had sampled, and they’d be like “what?!!” It was a wonderful thing, you know. And of course, the great thing is, I learned about their music too. So, I gave them the tools to conceive about music – history, the political side, the geographical side, the personal biographies of the artist – and then they got me into music that I didn’t know about, like UK drill and trap. So, I got that back from them, and that’s influenced a lot of stuff we’ve been doing over the past few years.

That discussion is really important – there’s a tendency, I think, when you find music that is very genre driven, to kind of hold up the past through a very nostalgic lens, and be quite afraid of new material coming in. You see quite a lot of that in metal, which is a shame because music moves forward when people are exploring different things – like Sepultura mixing western heavy metal with Brazilian rhythms. That was something, but it’s rare, and can encourage a backlash, especially in the era of the internet.

Yeah, I think so. It’s funny, there are quite a few things that are damaging music in my view – certain trends that are very unhealthy. They’re not the trends most people imagine. Moving to a completely electronic medium… Spotify. I mean Spotify’s unhealthy financially, but not necessarily the format. Whereas there are things that I think…. One of the dangers coming from the internet is what I call hyper-formalism.

There’s that guy, Rick Beato. He does this “what makes this song great”. He did Stevie Wonder – Living for The City – and he doesn’t mention the political element of it, the civil rights aspect. Instead, it’s all this [employs very “media” tone of voice] “well, it goes to this C diminished 3rd…” [Laughs]

And I watched another one of his where he was complaining about his students saying, “they don’t have any original ideas – they keep trying to be like X”. And I thought, it’s your fault mate! You’re totally reducing music to formalism… to notes and whatever, particular rhythms. You know, write it down and formalise. This is how you do it.

That stuff is all over the internet and, to me, that’s a far worse for thing for music then some of the things that someone like him is criticising. Because people like him are completely compartmentalising music. Crushing creativity and also taking out the important social aspect of music.

What’s music for? It’s not just about writing dots on a page or doing a Pink Floyd chord sequence perfectly. It’s never been about that and yet now, it’s worse than ever. And that’s something that punk sought to overthrow.

It’s the opposite of what we did with our emphasis on mixing genres and loving technology, as long as it was simple technology that people could just get and learn. But it’s all over the internet now, and it’s a far greater danger to creativity. So, when people are learning guitar from the internet, or learning their instruments, they’re just learning to copy in such fine detail, they’re losing creativity. So, I think, on the whole, electronic-based music is far more creative than music based on conventional instruments, and I think that’s partly why.

I agree, and I think part of the thing with the internet is whenever you get an artist trying to do something different, the level of backlash levelled at them by their “fans”, it’s not surprising that the people coming up underneath that are thinking, “well, I don’t want to deal with that”. And one example was Suicide Silence, who tried something very different on their self-titled album, and there was uproar – the level of abuse was really ugly.

You know, that happens with every artist that’s been around for a while and tried to push. But it’s a very difficult balance that.

On our next album, I mean a lot of it is going to be recognisably Asian Dub Foundation, but we have gone into other areas that we, perhaps, haven’t gone into before. And, I think, we’re doing it quite successfully, but still, it needs a bit of work. And there has been a reaction at close quarters, you know, of “that’s this, you should be this; you should do this”.

And it’s true, an identity of a group as an entity – whether a band, or whatever – it’s as much about what you don’t do. There will never be an Asian Dub Foundation with a slap bass. You know. I used to… because I’ve been there from the beginning, the whole thirty years, I used to have this notion of an abstract ADF constitution – “thou shalt not use slap bass”. [Laughs] “Thou shalt not do, I don’t know, some sort of pumping sex song”!

So, you can go out of the area where your identity is defined. But I think we’re luckier than most, as we’re able to incorporate stuff and try stuff. Like the track Can’t Pay, Won’t Pay on the last album, the basis of that was writing a trap song. It doesn’t sound like a trap track at all. But we’ve done the stuff with newer material and contemporary genres, and it doesn’t sound like the genre we’re basing it on. I think that the band is flexible enough to contain that and that’s what makes it exciting.

And I think that might be why it’s lasted thirty years- that’s probably the secret to it. Being flexible. The new album shows how we can work with an incredibly diverse range of artists, and it still sounds like ADF.

The Iggy Pop is probably the most far out. But I knew that we could do it – that No Fun would work with a Bhangra rhythm. It’s like yeah, we can do that. Or a real down tempo kind of torch song, bossa nova thing, like 1000 Mirrors. And it still sounds like us, I think. And then we can do something with Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, who was a huge inspiration to us growing up. You know, but where would you find Nusrat and Iggy Pop on the same album? There can’t be many. I haven’t heard any others.

But I guess the fact that you are poly-genre… I think whenever I speak to the artists that I personally enjoy the most, they’ll talk about their love of blues, and heavy metal, and hip hop – I guess when you’re mono-genre, you’re more likely to be led, whereas when you’re open to the idea of music as a whole, you’re more open to change… I think.

Yeah, it’s an interesting point. On Culture Move, which was the closest we ever got to pure jungle, at the same time I had a lot of fun with the bassline, and I put the old devil’s interval on there – which is something… I mean all of us in the group, we all saw how music connected people.

We talk about poly-genre, understandably, but it sounds a bit naff and we always thought about what music had in common. I heard lots of things in different genres that maybe others didn’t. Perhaps because I came… I mean it was Syd Barrett and the opening track on Pink Floyd’s first album that made me want to play guitar, before I discovered things like reggae and hip hop and what have you. So, I had that, and I could hear things in other genres that maybe others didn’t, and ways to connect them.

So, here’s another story and I learnt quite a bit about how people interpret us. This is weird actually. It was Italy’s version of Britain’s Got Talent – Italy’s Got Talent, right? Really, you know, nightmarish [laughs]. Someone came on and did Flyover, one of our tracks, on Italy’s Got Talent. And it was really because the judges… one of the judges (it was translated for me), said “well, I think it’s very brave for you to do an Asian Dub Foundation song, because their music is so difficult, it puts all these different style together. Really, really difficult, so well done for trying such a challenging track!”

I thought, really? It’s like… I don’t think Flyover’s a difficult track. To me, it’s pretty straightforward, it’s a straightforward bit of punky jungle. Which is something that I’d like to say we invented. But, these Italian judges, they’re all like “oh, really difficult! Complicated music!”

It is quite strange to be in a group that absorbs different things, right form the start. Jungle, Dub, Reggae, Leftfield, Post Punk, and Indian music all at once, and for it to feel natural. It’s normal. It’s not that unusual for any of us to do it.

I mean there were great moments – one of my favourite moments ever, when I first joined, they’d written this track – PKNB – Ani and Deeder on the first album – brilliant track, one of the best, real militant, anti-racist jungle… classic ADF. And it goes from half-speed table and then into jungle. And Deeder was there with a couple of his mates, fifteen years old, and they wanted me to play guitar. They said “oh, can you play some reggae?”

I said, yeah.

They asked if I could play funky stuff, and I said yeah, and then they said “can you play jungle guitar?”

As if it was just another way to play guitar! [Laughs]

And I just worked out a way of playing along with this jungle punk track, where I just dampened all the strings, put this really heavy phaser on and [impersonates the sound] – totally abstract, right? And I played that, and they said, “oh yeah, that’s jungle guitar!”

That’s one of my favourite moments as a musician – these teenagers realising, on an instrument that even in the 90s… the guitar was totally alien to rave and dance music, but they felt that I’d made a jungle style guitar, and it just came about because I was playing with the guys, trying to find guitar parts for the jungle parts they’d written, you know?! It wasn’t that difficult, you know.

I think it’s because I’d given up guitar for a couple of years. I always played guitar, but I gave it up for a couple of years, while I learned to play drum machines and learned to programme. Guitar was very much out of fashion. It was Dr Das who asked me to come and play guitar again. I’d left it against the radiator, it was all melted. So, I came back with a different sensibility.

So, yeah, poly-genre… I don’t know. To me, the connections make it less than poly-genre. I don’t know what the word should be. I understand why people say it, though.

I suppose it’s the easiest way to navigate it, but you’re right, it’s about what feels natural to you based on your own interests and experiences.

I grew up in a household and, when people used to ask me about influences, I’d reel them off, but my parents first two dates in the fifties were Ravi Shankar at the Royal Festival Hall and Buddy Holly at the London Palladium – what more do you need to say. The original rock ‘n’ roll and Indian Classical music. And there you go, that’s my background. And those two forms of music meeting really underlay everything else that came on top, so that was a great advantage of having that mixed parentage.

Looking over your career, one of those things that hit me quite hard was that – when you emerged on the scene in the early 90s society was really quite fractured and fragmented and, as we got towards the end of the 90s, it felt as if there was a lot more hope – you had people like Francis Fukuyama talking about the “end of history” and the phrase “melting pot” was in common usage; but it really felt like we’ve taken a lot of steps back, to the point that Comin’ Over Here really reflected the same sensibilities that existed back when you started – and, of course, that was reflected in the recent riots. So, I was really interested reading about your response to the riots, because I think it was you on stage who said: the riots happened, but less talked about were the sheer number of anti-fascists. And I was really happy to hear that kind of positive take on something that felt intrinsically negative.

That was a warmup gig in Brixton before we did Boomtown. And it was the day after the response came out, you know – where the fascists were meeting was distributed and everyone came out. And there were only a few of them, which is usually the way that happens with the far-right thugs. They back off, they run away, they run a mile every time. And, maybe it won’t last, but it threw a little bit of a cultural bomb.

There’s been this unholy alliance of incredibly posh, privately educated (nothing against privately educated people, but against this lot) people from financial hedge fund backgrounds – like Nigel Farage… all of the MPs, they all go on about being men of the people, but four out of five of them are Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank… Nigel Farage himself is privately educated: Dulwich College, international financial trader – it’s a joke.

And it’s all these people on Talk TV, like Isabel Oakeshott – they’re all super-posh, and they all go on about “the white working class” as if they’ve got anything to do with anything remotely working class. It’s a really sick and twisted game. Because they don’t have to bear the consequences of the incitement.

But they saw what their words can lead to and what they’re enabling, and it’s knocked them off their perch a bit. They’ve seen the Frankenstein’s monster they’ve partially created, or wholly created. So, they’ve given an expression from way up above in the ivory tower to a lot of violence at the bottom, and it was good to see when… you know, who are the people who do this? The Daily Telegraph, the Express with their anti-immigrant, blah blah blah headlines; and, literally, the day of the gig… I mean, I don’t look at those rags, but they’re in the supermarket; I was absolutely shocked to see in the Daily Mail and Daily Express all these anti-fascist protesters. They were on the front page of the Daily Mail and the Daily Express!

So, it really broke up, I think, psychologically, the forward march of the right wing and their posh, intellectual backers. It may not last, because I think maybe the material conditions for it are still here, unfortunately, but it just shows you that it’s not unstoppable.

And to do an Asian Dub Foundation gig, the day after all that with this small London Crowd – it’s just so great to play London because we don’t do it enough – and it really was quite emotional, because the band’s whole ethos, our whole reason for being was restated. Not by choice, but by circumstance. Just naturally, people got it. Same at Boomtown, and it really made me realise that what we’ve been saying is still relevant and it can still help people. There’s still something musically, in entertainment, that can merge with their own need to fight what’s going on. I’m very proud of that.

I’m very happy with Comin’ Over Here. I was feeling quite guilty, actually, when that went mad on Twitter. It was like the best thing we’d done for years, and everyone was sat at home and isolated, and I didn’t feel I could be happy, it felt wrong! It was like, I can’t have success the day we leave Europe, and everyone was isolated with COVID. But I spoke to a few people and told them I was feeling bad, and they said “no, no, no! You brought a smile to our faces, it’s what we need!”

Someone said to me “we can shake our fist and laugh at the same time!”

And yeah, I mean, I would rather there didn’t need to be a group like this; I would rather that the lyrics that I wrote for Fortress Europe were not relevant. I think I might have mentioned that before. I don’t want to be the prophet of cybernetic terror dogs. I don’t want our music to be relevant. I don’t want what we’re saying to be relevant.

But, if this crap is going on, if we can lighten the load, or say yeah, there’s a musical element that can propel you, that can make you feel confident about fighting this stuff then yeah, I’m glad we’re there.

And I think one of the most important things about the Collaborations album is Broken Britain. Now that – OK, 30th anniversary, yes. We can get nostalgic. It’s the 30th anniversary. We can celebrate 30 years, but we’re not complacent. That track, Broken Britain, it was written about now. It was written now; it was written back at Community Music where it started in exactly the same way as we did 30 years ago. A studio facilitated by Community Music, a young MC talking about the state of the world. He’s a great hip hop artist, and he’s very witty, but on this one, with Asian Dub Foundation, he decided to talk about Britain as it is. And that was so important, I think, because it just shows that that model is still transferrable and still, and old fogey like me can still get a vibe with a young MC like Chowerman, and Nathan on the flute of course. It’s got some big jungle beats, some big guitars, and a very aggressive, powerful vocal. And I think that’s one of the best lines – one of the best lines we’ve had for years – he goes, “it’s broken, but it’s part of me”.

Yeah, he’s a Bengali guy, half Bengali, half British – “it’s broken but it’s part of me”. It’s powerful.

I’m hugely interested in the intersection of politics and music, and I always have been – there was a lot of research into the power of words and the power of naming things – Edward Said and his ideas of orientalism – and that’s something that I’ve seen… you mentioned the tabloids and Nigel Farage as well, and their thing is to attach these pithy phrases to groups of people, as if they don’t matter. So, you know, it’s a person; not, it’s an immigrant… no, it’s an illegal immigrant. And you don’t see people anymore, just these groups. So, the counterforce of Asian Dub Foundation is to provide a cultural counterpoint, and it’s more important now than ever, I guess.

As I said, our stuff seems more apt to the past ten years or so rather than when we were writing some of it, that’s the irony. No, you’re absolutely right. I mean, the worst thing for the far right is to put a human face on people that are being othered. I noticed that big time (and this is not a new problem, you know), with David Cameron, and there were (I think) Turkish immigrants coming over, and he talked about “swarming” British people. And they’ve all done it, they’ve used that term – “swarm” and that why we wrote that track, to reclaim the term. And, you know, then he found out that a little boy drowned, and a name and a face was given to the little kid that drowned, and all of a sudden, he changes, and all of a sudden, he’s talking about being really sad. So, when you give a person a name and a personality, that is the worst thing you can do for the right and the tabloid press. So, you know, a lot of people… I mean it’s interesting that the largest vote for parties like Reform UK are the places that have no immigrants. It’s because that othering is writ large.

Yeah, there are a lot of interesting studies about that. I live in Leicester and it’s interesting to see that we’ve had the EDL try to swing by on a few occasions, and they’ve always been sent packing. And you’d think the converse would be true in a city with huge diversity – and it’s one of the few cities that voted against Brexit as well. So, yeah, it is that kind of out of sight, out of mind mentality – which is why bands and the media putting a face on it, and reclaiming terms as well, as you said – much as the LGBQT+ community did with words like “queer” … the impact can be profound. But, of course, it can take years.

Yeah, and what we did with swarm was basically… I saw a program about what a swarm is – it’s the most advanced form of collective intelligence in nature. Like a swarm of bees, they collectively think 10X faster than the speed of human thought. So, you try to find depth to these words. “Alien” is a good one – the science fiction aspect to alien, when actually alien was an old term for immigrant. It’s just that the depths to these pejorative words are worth exploring.

Having said that, it doesn’t always work. I remember when I first joined ADF, a lot of hip hop (and still today) used the n word. It’s all over it and personally I don’t think that reclamation has worked in terms of a wider absorption of the word. Maybe in the communities that hip hop came from, but I don’t think it’s that constant – who can say the n word and who can’t. We did a little bit about the P-A-K-I word, as well. We thought we’d reclaim that, but some words you just can’t reclaim. It’s complicated that one.

Of course, and the other thing that you did very successfully with Comin’ Over Here was to juxtapose comedy and politics and that’s not an easy path to walk. Because, if you think about how Brexiters in the UK and Trump supporters in America kind of were lampooned, it didn’t serve to pull away the middle ground. If anything, it retrenched certain views. So, comedy can be a really powerful tool to open people’s eyes, but if it’s employed in the wrong way, it can come across as condescending and push people down a path that perhaps is not what you intended.

I think there are certain things that we have, and we’re talking… let’s other the far right, shall we? [laughs]There are quite a few instinctive weapons that we have in Britain, actually. Artistically the far right is pretty damn awful. There aren’t many openly far right artists in music and in arts, or even in comedy. There are comics that rail against the left and censorship and all that kind of stuff, but I don’t think they really embrace a far-right agenda. I don’t think Ricky Gervais embraces a far-right agenda, whatever you may think of him, do you know that I mean? So, I think, we have the more imaginative culture. It does work against the far-right, because they hate it but they’re unable to put anything in its place. Which is good. And also, I think, in this country, people start absorbing far-right ideas – the middle ground of Britain, if you like – but if they actually see the Frankenstein’s monster of it, they back away, and we saw that. That might not happen in some other cultures. There is a certain moderation in British culture that doesn’t like being associated with far-right thugs. That’s not to… I’m not sure how strong a weapon that is, but it’s a little guard But I think we might have reached peak far-right on the streets.

The problem, as you kind of mentioned, is there have been a lot of TV shows, and tabloids, and wealthy, privileged people giving it a veneer of civility and sort of burying the violence…

A veneer of intellect!

And sometimes it goes the other way. Nigel Farage – it’s an amazing con trick that he’s some kind of man of the people. Same as Trump, you know. They’re the most privileged people to walk the earth! You can’t get a more privileged person than that. It’s very cynical, and they know that they’re doing it. It’s like Chowerman, the MC – “why are they doing this? Money and attention”.

Ego, and billionaire trust fund think tanks, blah blah blah, and that whole system. That’s what it’s about. The irony is that none of these people will do anything about immigration. All they do, and this is the scary bit, all they do is performative. God forbid Reform UK get into power, what they’ll do is a whole load of stuff like they did in Peckham – or tried to do in Peckham but failed – which is to have a load of police vans come and bash heads of asylum seekers. It’ll be all over TV – “look, we’ve done it”. But if their backers then say “well, hold on one minute, we like this cheap labour”, then they’ll just camouflage / massage / divert… that’s why the Tories had all these horrible, complete sell-out, neo-fascists like Patel and Braverman, and they’ve done nothing about immigration. It’s increased. Why? Because 25% of the Conservatives’ money comes from the construction industry. They don’t want to stop cheap labour. The great irony is that the only leader who would have prevented or slowed immigration is Jeremy Corbyn who would have increased wages at the bottom of society. That’s the great irony – the only thing that will reduce immigration is a socialist economy. But Nigel Farage isn’t going to tell you that, is he?!

But there’s a larger problem, and I’m not a person who normally blames the advance of technology for problems. But the runaway information society that we have now, where you’re basically machine-gunned with so much information, and It’s all; based one way or another, and you’ve got confirmation bias, and it leaves most people overwhelmed. And all they’ve got left is an emotional response. That is the big problem now, I think. The internet has created a knee-jerk emotional response because it’s really fucking difficult to take it all in. even Farage himself said that the Brexit vote was an “emotional decision” when he was interviewed. I mean God almighty! You take a decision like that on an emotional basis and then you lord it! We really are in fascism, because the whole thing about fascism is the rejection of reason> That defines fascism more than any other factor 0 the rejection of reason. The rejection of rational debate. The rejection of weighing things up objectively. Fascism is about irrationality. That’s what it feeds on and unfortunately that’s why the internet has allowed irrationality to grow- conspiracy theories. Some of the most absurd things now drive mainstream sections of the media.

And it’s really challenging to address these things in music, because it’s fundamentally an emotional art form, and it’s very difficult to craft nuanced lyrics. Any anyway, it’s very easy for people who don’t like those lyrics to overlook them to the point that we’re seeing people surprised that Rage Against the Machine are against the right…

Yeah, that’s a funny thing that. When we opened for Rage, and we weren’t advertised on a couple of shows, and we played in Barcelona and the first two or three rows all had these kind of fascist t shirts. Far right Spain, and they looked at us and all turned their backs. At a Rage show. The thing is you can’t control how people interpret your music. You don’t have that control. That can be a wonderful thing. But once your music’s out there it belongs to the world, it doesn’t belong to you. You have no franchise power over what it means to people. So, some people on the far right, you know (where English isn’t the first language perhaps) they like the aggression and power of the music and they think that Rage is singing for them. I mean, we’ve had all kinds of crazy interpretations of our music. On the great side, one of my greatest pleasures is when someone says, “your song means this” or “it made me feel that”, and I’m like, oh right, I never thought of that. That’s great. You don’t own music. Art generally is about the relationship with the person who receives it. So, one person’s interpretation is just as valid as yours. OK, if it takes a meaning that’s really horrific, maybe you correct them, but on the whole, I mean… I remember John Pandit was DJing in Bosnia and they wanted them to play a very aggressive track from the first album, and they kept asking him and he said he didn’t have it, and they told him it’s what they played to get going to fight against the Serbs. It was used to rile them up for war and we didn’t intend that. But it’s an aggressive song, and it does mention violence, no doubt. But how would you ever know, when you’re sitting in Farringdon in 1994, and you’re playing to thirty people in the local pub that, in a year’s time, people in Bosnia would be using your track to rile them up to start shooting.

I suppose that’s the difference between catharsis and incitement.

Yeah, people have tried to blame music for all kinds of things. It’s one of the classes I do, actually, music as threat. I play them a grime track – Pow (Lethal Bizzle); and I also play them Link Wray – Rumble. Some people say it’s the first heavy metal record – 1956. I ask the class what they have in common, and no one gets it, normally. But they were both banned by the authorities for sparking violence. Pow – they created new police legislation, order 303 I think, but police would go into raves and tell them they couldn’t play the record because it supposedly incites people to let their guns off. And Link Wray’s record was banned because it apparently started fights in bars. And the interesting thing is, it was designed to star fights in bars. It’s about a bar fight, and it sounds like one. That’s another aspect of music.

But then, sometimes, music that sounds like it should start rebellions is written by conservatives. The Ramones – it was revolutionary music, but some of them were real right wing, Reaganite types. So, the link between music and politics is not what you think. It’s not just writing political lyrics. Sometimes we used to get tapes of people saying, “you’ll like this, it’s political”, but the music’s boring. The music has to sound revolutionary. Jungle doesn’t have lyrics half the time, but it sounds like a riot! Our instrumentals, I think, are just as challenging as a track with lyrics. It’s like Public Enemy – their music sounds like an uprising. It sounded like the next stage. Whereas you want to get an acoustic guitar and sing anti-government songs, it’s impotent. I’m not writing it off entirely, but generally it’s the most boring way to make a statement – the old Dylan style. It’s not going to turn anybody’s head. It’s got to be challenging, exciting – you’ve got to sound like the next step. That’s what we always thought. Obviously, after thirty years, I’m not so sure I’d be so arrogant as to say we sound like the next stage. But I think we can say it’s pretty good to have tried to sound like the next stage after thirty years.

Looking at the compilation album, one of the tracks that I thought really stood out was your cover of a Stooges song. You tend to think of them as a punk band, but it really underscores how unique they were, because it’s totally different from say, the Pistols or the Clash. They were very diverse – something that also showed when Bowie produced the Raw Power album.

I actually think they’re the most radical of those bands. I mean, Fun House – the second side is basically jazz-punk. All that wild free jazz sax. Yeah, they definitely had their own thing going on. I finally understood it, actually, when I saw an interview and they worked the same way James Brown worked. And obviously they don’t sound anything like him. But we all know that Iggy Pop is a wild performer, but actually it was his performance and movements that made the band play like that. The band literally watched Iggy and then played music to match his movements. And that’s what the James Brown band did. He had every instrument play a rhythm he could dance to – the same with the Stooges. I found that out and that was incredible.

That makes so much sense. I’ve never heard that.

The first two Stooges album have these very simple, hypnotic rhythms and, when they got to the studio, their songs were ten/fifteen minutes’ long. They had to cut them down. So, basically, it’s all really cyclical riffs, which is kind of what post-punk was like – like Joy Division. You had these bass, guitar, drum cycles. The drummer of the Stooges, he was playing totally against the drumming style of other rock music of the time, with big drum solos and what have you. He was like a robot, and the reason was that he was watching Iggy dance, and he was hypnotised. So, that’s why, when we were talking to Iggy, he was such a fan. I was amazed, he’d seen us a few times. I was amazed. And he said, “you’re a very difficult act to follow!” You’ve got to be kidding me, man! I’m going to have that engraved on my gravestone! [Laughs] The ultimate performer, someone who set new depraved standards in performance, said that were a difficult act to follow. What the hell?! So, I realised… not many people in the band knew him. Maybe they knew The Passenger, but I don’t think that’s a song that ADF could have got behind. It would sound pedestrian. But the Stooges one, you could put Bhangra in No Fun. There’s a lot of alcohol, a lot of madness in Bhangra. It’s a direct, people’s music. It’s vibrant, and mad. And I thought that would be really good. The subtitle of it was No Fun (Punch Up at An Indian Wedding Mix) – that was the original title, a sort of joke. We didn’t use it, but that’s what I had in mind – the drunken lunacy of a crazed, drunken Bhangra wedding night. So, yeah, it’s a kind of weird connection, but it worked.

Of course, we had none of the original instrumentation from the Stooges, so we sent a demo, and Iggy sang over it, and then when we got the vocals back, we built it up. I’m glad we got a second chance to look at it again, because the guy who did it, a guy called Bernie Gardner, I think he did a good job. So, basically, he took the original mix that we did, and took it apart a bit, and I think he made it a bit more guitar oriented than the first version, and it seems to work.

I like the idea of collaborative albums because it sits at the heart of the idea of music as a community, and the fact that you’ve got people from such different musical backgrounds – it’s created something that stands really well, and it flows beautifully as well – it doesn’t feel like a compilation if that makes sense.

No, I know! I’m really, really happy with it. We’ve had a couple of compilations before, but this is more than a compilation. It’s more of a statement of what’s possible, I guess. That’s what it feels like to me. I mean, Sinead, Iggy, and Nusrat all on the same album, and then these Japanese future-dub acts. And you’re right, it does seem to flow> I thought it wouldn’t, but it does.

It’s a huge part of making an album is to create the flow that keeps people hooked. It’s such an underrated skill and especially here, pulling together a compilation and getting the mastering right and the sound right so that you’ve got that journey… it’s worked really well here.

I really like it a lot. I think it is some of the best moments of the band, I think. I really do. I mean we’d never done anything like 1000 Mirrors before or since – I mean how could you, with anyone but Sinead.

That one was like, yeah, I was writing about the origins of that song, and what was amazing was that I was listening… it was based on a loop that Pandit G put up, and I basically played all the chords and the guitar line just on the spot, but I had no idea that Sinead was going to sing on it. And I was listening and thinking how to develop the song, and I discovered this tradition – the Bhajan – which is Hindu devotional music, often sung by a woman. It’s really beautiful music, and I found this album, which was a whole load of songs devoted to a female rebel saint in the 16th century in India. Remember that I had no idea that Sinead was going to sing on this song, but I went through making this track like a devotional song to a female rebel saint. And, of course, if you’re going to talk about a female rebel saint, that’s Sinead O’Connor, isn’t it. So, that was a bit of magic, and I woke up one morning with the title Land Of 1000 Mirrors on my lips. No idea why. I found out later it was something from Indian folklore that had been in my head. And it was after all that, I went to a meeting about the case of Zoora Shah and heard her daughter (who’s now a labour MP), talk about the situation and so The Land of 1000 Mirrors became 1000 Broken Mirrors. Then I did a demo with Sonja who sings on a lot of our albums – she sings on Fortress Europe. Then, Adrian Sherwood played it to Sinead, and that’s how that happened. And, then Ed O’Brian came in on second guitar – happy times! It’s the only time ever I’ve been in the studio with a second guitarist.

Other songs that stood out – obviously, it’s such an important track – but Black Steel in The Hour of Chaos. It’s a song that’s been picked up by a lot of different artists from Tricky to Sepultura

Sepultura did a version, really?

Yeah, it’s on a great EP called Revolusongs. They also covered Massive Attack on it.

I didn’t know that. I met Max a couple of times. But this was after he left, right? He was a big fan of ADF. I think he did talk to me about a possible collaboration, but I couldn’t find a way in to do something with that kind of sensibility at the time. I have to work on instinct with collaborations. Sometimes, if someone rings me up and says “yeah, we should do a track together”, it’s not the best way of doing things. It’s very much record company vibes – “you should do a track because…” I tend not to… I almost shy away from that. All the collaborations on this album were spur of the moment. Like me and Iggy Pop had a laugh about it. And we ended up doing it. Sinead heard the track and when I heard she was going to sing on it, I was stunned. I didn’t know Adrian was going to play it to her. MC Navigator, that wasn’t even meant to be an ADF track. And that had a really long gestation. It doesn’t sound like it, but it’s probably the least spontaneous of all the tracks. And the Chuck D, again, was a… we hadn’t rehearsed that. That was totally on the spot. What you hear there, on the spot. We put together a backing track that followed the lyric. God knows how it worked. We hadn’t rehearsed it with Chuck at all. He literally just walked on, and we stuck it on. And it worked out correctly, so all the changes were bang on. But it was really fantastic. It was just a kind of weird, left field version of Black Steel – which is probably my favourite Public Enemy Track – nothing had ever sounded like that.

Collaborations are interesting because it can be quite vulnerable. It’s hard enough putting your tracks in front of people you work with on a regular basis, and I think you can feel it when it’s been done for, shall we say, commercial rather than artistic reasons. But yeah, collaboration is a difficult thing to get right.

It is. And it has to have an element of spontaneity and enthusiasm. If someone just say you should do it, it doesn’t even matter who it is. It could be anyone, even someone I really like; but if it’s a scheduling thing, it just doesn’t work; I instinctively shy away. I mean, yeah, I’m trying to think how the other tracks came together, and I think pretty much all of them had some kind of surprising element to it.

How about Broken Britian? How did that come about as the new track on this album?

That one came through Nathan. We just wanted to work with some younger MCs. I actually wanted to stop writing lyrics. I didn’t think I should be writing lyrics for other people to do. But what I wanted to do was set themes for what other people might not otherwise have said. Chowerman normally does comedy diss tracks. He’s never done a track that talks about his life in Britian and the struggles. But yeah, he comes at it with a really 2020s style and it works, and I think it’s an interesting thing for him. So, we’ve written quite a few more with Chower, and with another guy called Blackk Chronicle. And I kind of subtly made suggestions, right. I didn’t want to stop them from writing anything, but you know p why don’t you write about “we” rather than “me”? Or why don’t you write about how crap it is now as we approach the election? And he came back with Broken Britian – a really terrific set of lyrics that are, perhaps, more ADF than ADF! It’s a jungle punk thing with 2024 energy. That’s the one. That felt the most ADF of the new stuff we’ve done, but at the same time it’s about now, and that’s how it made it through to this album. I think it’s really important, just to say that we can work with much younger MCs, and we’ve still got something to say now. It’s not a nostalgia trip. It’s an exercise in the development of a methodology and purpose, if that makes sense and doesn’t sound too pompous[laughs].

And that’s the thing – it’s about what feels right to drive the song. It’s like we were discussing earlier – the hip hop acts like Cypress Hill were digging into all kinds of music to create their sounds, and they didn’t care about genre, they just knew what sounded right.

Yeah, the guys at Def Jam. The one that blew me away. The first one I heard like that, it wasn’t Public Enemy or Beastie Boys, it was LL Cool J and Go Cut Creator Go, I couldn’t believe it when I heard that record. It samples Chuck Berry and Jimmi Hendrix, all on the same track and it was the first time I heard that, it gave a new lease of life to a guitar sound, as far as I’m concerned. And I think that’s what happens when music moves on. Rock, now, is a palette you can draw from. It’s not a happening, era-defining musical form, but it’s something you can draw from. And that’s what happened to jazz. By the end of the sixties, you’d got to free jazz, there was nowhere else for it to go unless it started merging with newer forms of music. And that’s where Miles Davis took it. That’s when the time of a genre has ended – it starts featuring newer forms of music, and that’s what I’m interested in. There’s always going to be a place for an aggressive guitar, but in different forms. Interestingly, some of thew UK drill music is guitar, bass and drums. Samples, for sure, but it’s often some melancholy, arpeggiated guitar. It’s amazing, you know, but it’s guitar, bass, and drums.

And you’d be surprised. A lot of people in my class into absolute now music like trap and drill – they’re so open to listening to other music. They love it. The prejudice is more from older people criticising young people’s music. Whereas the young people are open to all kinds of stuff. The stuff that Blackk Chronicle and Chowerman know is amazing, so it really annoys me when people say “oh music’s terrible now, it’s destroyed” when younger people are really open to all kinds of music.