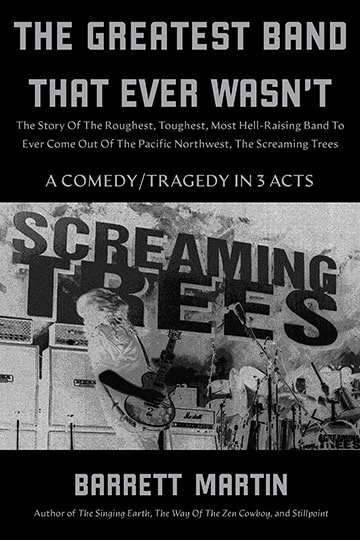

Whether you know him as a much-travelled ethnomusicologist, a capable producer, the pulverising force behind the Screaming Trees, or the multi-talented, multi-instrumentalist behind Mad Season, Barrett Martin has had a truly remarkable career in and around music. His passion for his art is visible in every project he undertakes, and his recent book shows not only his love for the form, but also a rare ability to spin a tale of life in a frenetic rock band, free from the usual name calling, scurrilous detail, and bitterness that so often infects the form.

With such a career, finding questions for Barrett is not a problem so much as curtailing the list of questions to ask. And, as I dial into the Zoom chat, I am very aware that for me, as a lifelong fan of both the Trees and Mad Season, this is a rare opportunity to dig a little into some of the music that has meant a great deal to me over the years.

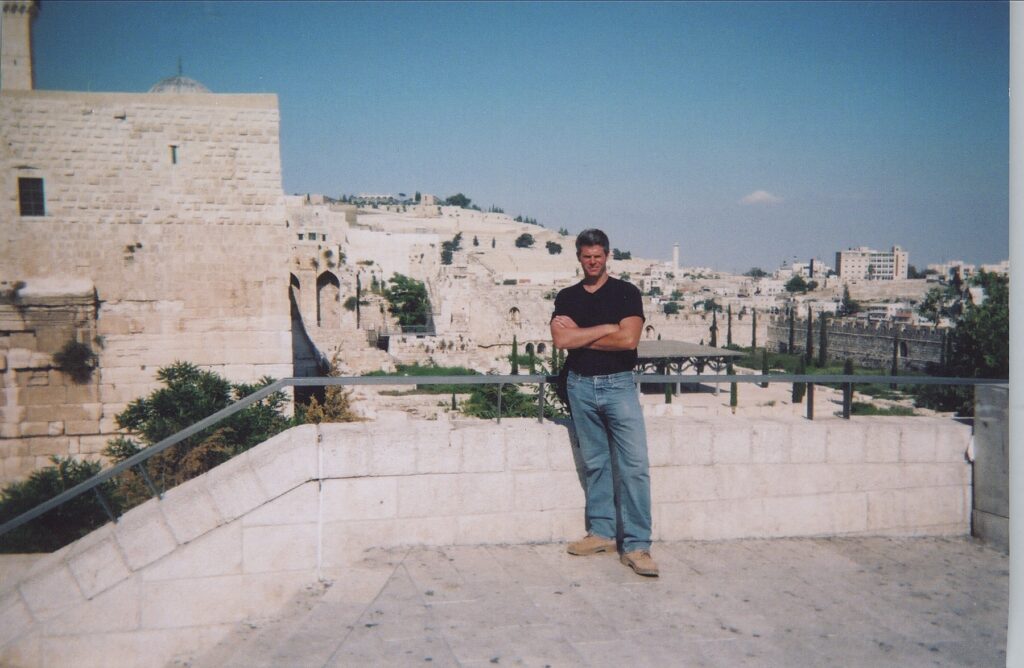

When Barrett comes on camera, he’s in his studio – a remarkable space filled with an array of acoustic instruments. He graciously gives me a tour before we get down to the questions, and then it’s time to pose the first question. Throughout the interview Barrett laughs often. He’s as generous with his time as he is with his praise for the musicians with whom he’s worked and played over the years, and he tells a great story as you shall see. Moreover, you get the sense that this open, honest, and passionate musician would have found a path to ethnomusicology and recording, even if he’d never had a successful record in his life – he exudes a joy for the subject that is truly infectious, something that is equally visible in the trailer for his forthcoming VEVO series.

Hey, how are you doing?

Hi, how are you?

I’m fantastic thank you yeah, it’s a cold and stormy evening here in England.

Yeah, this year it’s… I mean we made it through that Blizzard but now it’s just really cold rain [fiddles with camera]. One minute – I’m going to get this – let me check you can see me?

Yeah, I can see that amazing studio background. I’m suffering all kinds of gear related envy!

Well, you know, most of what’s back here is acoustic stuff. It’s like, you can see Marimbas, vibraphones, there’s an upright bass on the floor. The amps and guitars are mostly in the back, in a room behind the velvet curtain – there’s like another room back there and it’s not exactly an isolation booth, it’s just another room.

Most of the stuff I do here is is my own projects, I don’t really bring bands in here, because it’s not really set up to be a band studio – it’s more like the stuff I do. I just walk around the different instruments and do overdubs. I mean, I can do overdubs on other people’s albums, or stuff that I’m producing, but it’s not isolated enough to do like a rock band.

I don’t even do that much rock stuff anymore. I mean, I’m not opposed to it, it just doesn’t come across my doorstep as often.

It’s really important having that workflow – one of the things I’ve found is, when you’re younger, you tend to have mess everywhere and you clear it up to play or record, but as you get older, it feels like another barrier to getting to work, so it’s important to keep everything ready to go.

It’s actually quite amazing how you can record with very little – you don’t need a huge amount of gear [takes me on a mini tour of his studio].

I’m always excited to see the recording spaces people have, because every environment is unique, and there’s something so cool about being in a recording studio and anticipating making something amazing.

Well, if you’re going to make high quality records, you sort of have to have this in addition to be able to go into a big studio. The budgets I work with – the bands that I produce or the singer/songwriters (I work a lot with singer/songwriters) … even the bands on major labels don’t have very big deals anymore.

The days when we made Screaming Trees records that cost two or three hundred thousand dollars – and that was quite a small budget back then – you could make a good record, for sure, but it wasn’t like a big budget. It was just an average mid-range band budget. It was enough to pay for the studio, enough to hire a good engineer, pay the producer – the band’s not going to make any money, but you could make a good-sounding record.

Nobody now, unless you’re a huge pop star, gets budgets like that. So, everybody, especially if they’re on an indie label, you have to have some sort of studio space where you can do focused work for a good amount of time and not spend tens of thousands of dollars. It’s just the contraction of the music industry. It’s no secret. If you are still in the industry and producing records, this is what you deal with on a daily basis.

That was one of the first things that blew me away reading your book, though. I grew up on alternative rock, particularly the music coming out of Seattle. Screaming Trees was a huge band for me, and, from an outsider perspective, you were huge. You were on Epic! When Dust came out, it was racked from top to bottom in Virgin… and then I open your book and, right at the beginning, you’re talking about recording Sweet Oblivion and not having any food! It’s so eye-opening.

That’s absolutely true. OK, so, I think the budget for Sweet Oblivion was one hundred and fifty thousand dollars. And that gave us a little more money than they gave the band for the first [major label] album. And I didn’t play on that one, but it was called Uncle Anaesthesia, and I don’t know what the budget for that was, but we got a little more for Sweet Oblivion.

So, it paid for the studio, it paid for the producer, it paid for the engineer, and it put us in a pretty grimy hotel. It was the Gramercy Park hotel which, now, is super-fancy; but back then it looked like the same décor as the 1930s, but like sixty years later. So, they gave us car vouchers, so we could take these Lincoln town cars to the studio, or to a meeting or whatever, but they didn’t give us a per diem for food! There was no food budget. I mean, I didn’t have any money back then, and I don’t think those guys did either, because we were all complaining, like “fuck man, we’ve got no money to go to dinner!” We had no money for a restaurant. We could buy slices of pizza form the corner pizza place or get some French fries or whatever. Our A&R guy would take us out once in a while and let us order extra food so we could take it back to the hotel, but like, that was just the mentality of major labels back then. It’s probably not any different today.

It’s such a perfect example of being on the outside looking in. And then there’s the story of where the frustration of all that boiled over, and you pegged a can of beer in the direction of Mark – and I was thinking that it’s such a great story, because it’s in moments like that where – you were relatively new to the band – either friendships are made, or lifelong enemies!

Yeah – Mark and I bonded over that moment. I think we were both hungry. I mean, Sweet Oblivion is a lean-sounding record, right. It’s very well produced, but it doesn’t have a lot of stuff on it. It’s just a four-piece rock band with a little bit of keyboards and we were lean and hungry and the record mirrors how the band was very accurately.

Yeah [laughs] Mark, he wrote the story too – it’s not just my story. And it’s funny because we’d been bragging about our high-school athleticism. And I was actually a pretty good pitcher, but apparently, I can’t throw a beer can. And so, we laughed and yeah, I think in that moment we realised that we were on the same side and maybe more similar than not.

One of the things I found in the book is that you’re very honest about everything really. You’re very clear-eyed about how good the Screaming Trees were musically, but also what went wrong. And I think, very often in this type of memoire, there’s a tendency to point fingers, and that’s something that you managed to avoid with remarkable clarity and I was wondering how much of that came about because, you’ve done a lot of academic study, and I wondered to what extent that helped give you the necessary detachment to write with both passion and clarity?

That’s a good observation because it probably…. OK, let me say it like this. When the Screaming Trees broke up in 2000, I was already doing ethnomusicology around the world. I’d been in Africa and South America, and a few other places, and then I went back to school to study it academically, up to where I got a master’s degree. And, when you write about music in that context, you are supposed to be this detached observer, writing about what you’re seeing and hearing, and you know, the programme that I was on was an anthropology programme, because ethnomusicology is a part of that, so you get a lot of this training to remove yourself as much as possible.

Well, something like the Screaming Trees, I can’t really remove myself because I was in the band [laughs], and I was an observer and a participant at the same time. But I kind of have a couple of personal things about… I definitely tried not to point fingers at anybody. It’s just kind of a general rule: if you’re going to talk about the shit that somebody did, you better be able to talk about the shit that you did, or somebody else will [laughs].

So, what I tried to do, and I think I was fairly successful about it, was to really talk about the great talents of the band and particularly their song writing ability. Because even though the Trees didn’t have the success that the other bands had, everybody knew the quality of our songs. I just read this quote by Cameron Crowe who directed Singles and oversaw the soundtrack. He said, even though the Screaming Trees were not in that movie, and we only made it on to the soundtrack at the last minute, everybody was playing Screaming Trees songs while they were making the movie. So, our music was kind of in everybody’s consciousness in the Northwest, and then it grew beyond that, but I didn’t want to ruin the legacy of the band by saying “he did this” and “he did that” because I did as much shit as everybody else.

And the other side of the story is that, as talented as everybody was; all four guys in the band, each had a really cool talent – here was no weak player in this thing; but each had their own issues. So, the combination of the creative and the destructive aspect – the destructive was as powerful as the creative. It’s the thing that tears down most bands, anyway. It’s not always about alcohol and drug addiction – ego and narcissism can tear a band apart as much as alcohol or drugs. But yeah, I don’t like to point fingers or name call or anything like that. I try to be objective about what happened. That’s why I liked Lanegan’s book because I was there when 90% of that stuff happened. It’s true. He’s accurate about what happened, but his experience is very subjective to him and very different from the rest of us. We each have our own experience you know.

So, I know that’s a long-winded explanation, but the point is, if you start pointing fingers and name-calling, you make it too personal and you’re not able to tell and objective story.

I think it’s a really fine line to walk, because there’s that detachment necessary to tell the story with a degree of objectivity and yet there’s still that need to keep the passion there. Living in England, I could only observe what was happening across the pond and read about it in the Melody Maker and the NME and it was huge to us – the Seattle scene was kind of magical in the way it arose and was portrayed – so I guess, when you were living through it, it was just your life, but from over here, it was like some Hollywood story.

Well, we felt the same way about what was happening in London. When I was coming up in the 1980s, my favourite bands were all British bands – the Clash, Stiff Little Fingers, Buzzcocks, XTC, and Killing Joke – so, yeah, the coolest bands in the world were the British bands… I know they’re not all from London, they’re from different cities. And, when I was a sophomore in college, I did a semester as an exchange student studying technical theatre in London (it’s not what I majored in, but I was interested); so, I spent a few months in London when I was 19, and I was really affected by that.

So, in Seattle, we saw all this stuff happening, and England seems small, physically compared to the US, but it’s got a huge music scene. So, a lot of us were influenced by the punk and new wave – that’s a big part of the Seattle Sound for sure.

That’s another thing I liked in the book was how generous you are and how open you are to the music of the bands you played with; you picked up on the Manic Street Preachers – a fantastic band – and you mentioned Dinosaur Jr and a lot of the Seattle bands – but it’s interesting to read a biography that not only covers its source material, but also opens up these other avenues of musical exploration. Reading the book kind of reminded me of how I grew up reading the liner notes of albums and trying to find other bands through those, and I really enjoyed that aspect of the book – it’s a very cool part of it.

Well, I mean I’m 56 years old, so I grew up with reading liner notes. In the 70s and 80s… yeah MTV started in 1983 or whatever, but aside from that, you really only learned about a band by reading the liner notes on an LP and maybe you’d get a magazine that had a story. But I grew up in Olympia Washington, and it wasn’t even Olympia, it was way out in the woods. We didn’t have stuff like that, and I didn’t even have the money to buy magazines. I would just get the albums.

Another interesting thing in the book was learning that it was you doing the introduction to Gospel Plow and then tying that together with the things you did in Mad Season…

When I started co-writing songs with the Trees – I co-wrote some of the songs on Sweet Oblivion – but yeah, some of the songs were done when I joined the band, in a sense that the essence of the song was done, although we still had to arrange it and tweak them a little bit. I had this background where I was in music school in the 1980s, where I studied arranging. I was a jazz student, I studied arranging and composition, so I would hear one of their songs, and it would just have a verse and a chorus – like the best part of a song, but I’d figure it needed a bridge or an intro, because it was starting too abruptly. So, in that instance, you’d need something to build it up, because that kind of makes it more interesting, and the band were kind of like “well, write something then!” So, I would, and then, as a band, we’d massage it and get it, so it fit.

So, that’s how I started writing songs. It wasn’t coming in with my own songs, but by taking what they had and just basically making it a little more sophisticated – it wasn’t so punk rock, it had a little more depth and a little more arrangement. Then, I did a lot more of that on Dust. Especially on Gospel Plow, because when the drums kick in and the song starts, it’s cool, but it’s a very abrupt… you need something to set up a song like that. I mean, you could start like that, but if you want to make it a little more interesting, then it needs something. So, I’d bought a harmonium, and I was dabbling in Eastern music at that time and Mark… because Mark and I worked on that, I worked on the musical part of it and Mark and sang, and then the song began. So, I mean every song is different, right? I have a pretty good memory of how certain songs came together, others not so much. But that song came together really well, and I remember how that was conceived.

I remember, I think, Pink Floyd giving an interview – probably around the time of Dark Side of the Moon – where they talked about how part of their progression was learning how to use the new instruments (specifically, I think, it was the briefcase synth), and that’s always really interested me. I think, when you’re learning any new instrument, it kind of encourages you to write in different ways, and it strikes me that you’re quite similar and, as you’ve gone through learning about new instruments and styles form your travels, you’ve brought those elements in and that’s what’s kept you moving forward over the years.

Yeah, for sure. It’s funny you mentioned Pink Floyd, because not too long ago I watched a short documentary about them making DSOTM and it shows them playing those old synths, where you have to plug in the patch cable, and it’s really cool because it looks like they’re learning how to play it for the first time, like “oh, what if I turn the knob this way?”

I have some synthesisers I got not too long ago and I’m still figuring out how they work, and a sequencer and I’ve made some demos that may or may not turn into songs that I eventually release.

But to be honest, I generally like acoustic instruments. I like the way acoustic instruments sound. Everything behind me is acoustic and I have a whole bunch of acoustic guitars and stuff I got in the middle east like Arabic instruments and stuff like that. I really love the way they naturally sound. But I’m also not opposed to playing around with Synthesisers, or interesting keyboard sounds or effects. It’s not what I’m known for, but I’m not averse to it either.

I remember I was talking to Mark, and it was not long before he passed away and that was totally unexpected because he and I were in communication about a few projects I was working on and he helped me with – and I was talking about the album that he released when he put out his memoire (Straight Songs Of Sorrow) – it’s very electronic. It has a lot of electronic sequences and I said “man, this is cool”. I really liked it, but I was like “where did that come from, I had no idea you were into this!” and he was going through a phase where he was going back and listening to like, the German bands, like Eisturzende Neubauten and Kraftwerk, and he was revisiting that, and it influenced how he wrote music.

So, I think what’s cool about that is that Mark had that philosophy that, as you go forward as an artist, you always have to be doing something new – something different, so that it pushes you out of your element and you’re reaching for new ground. So, even if it it’s just for yourself, you don’t necessarily have to reinvent the form, but you have to do something that challenges yourself. So, inherently when you do that, some new idea will come from that, and I think he did that really well.

I was inspired by Mark’s ability to reinvent and recreate, and I think every great artist has to do that – you have to always find a new way to express yourself. It can also be different mediums – I read this interview with Joni Mitchell who said, “I’m never not creating, because if I run out of song ideas, I paint”. And she’s a beautiful painter, so you can have a new expression in a different art form to help you get ideas for whatever you’re known for.

Yeah, and that sort of excitement – you mentioned acoustic instruments there and I gave synths as an example – but I think it’s the same with acoustic instruments. I remember picking up a cigar box guitar for the first time, and I got one from some thrift store and it was horribly out of tune, and I had no idea how to use, but it immediately went on to a track – it’s just that sense of trying something out.

I’ve got to try one of those!

They’re fun!

I have a friend in Seattle who makes custom cigar box guitars, but that’s a good example, because that is a sound that you cannot recreate. I mean, someone’s probably made a sample somewhere, but it ain’t going to sound real!

I love it because it’s those happy accidents that you don’t get with samples. Even a weird bit of feedback can change the experience you get on a record, from something that’s maybe a little sterile to something uniquely organic and it’s that kind of thing I find really exciting.

Well, two things. When I was in Africa… five years ago, I was in West Africa studying with drum masters. All the instruments that sounded the coolest were a little bit janky. They’d hammer bottle caps onto the instrument to make it buzz, or pieces of wax paper and cellophane over the resonators of balaphones or things like that, so it has this buzzy, slightly out of tune… but that’s what makes it sound so cool. If it was perfectly in tune and clean sounding, it wouldn’t sound like an African instrument. It would lose its essence.

And then you mentioned feedback. So, Peter Buck from R.E.M. is one of my oldest friends. He and I were adding up the number of albums we’ve worked on together, either in the back-up band, or one of our projects. We’ve worked on thirty-five albums together! Just the stuff that me and Peter have done, you know, backing up singer-songwriters or the couple of R.E.M. records that I played on. We just did a quadruple album in Brazil – that’s what we were working on last year. And, you know, he’ll spend a day in the studio, just making feedback with different amps and guitars. Just making feedback that can be used somewhere in a song. It’s a sound palette.

It’s that kind of hanging off the edge and doing unusual things that make certain sound engineers grind their teeth – it’s the most fun that you can have in the studio.

Yeah – well, if it’s done right and it’s not abrasive sounding – it doesn’t hurt the ears, it’s like “ooh, that’s a cool, spooky sound – let’s sneak that in a little bit”.

It sounds like, right from the beginning, you had a producer mindset, but at what point do you think you moved from more of a musician perspective to having an interest in production?

Well, I think I always had a producer mind. I started as a drummer, but I also played upright bass – like at the same time. In music school, I played drums, upright bass and piano – that’s kind of required. I’m not a very good piano player, but it does help you. And all of that stuff helped me to understand the structure of music. Even if you’re in a band, if you come in with that kind of philosophy, you’ll start to think of things like a producer.

If you only think of yourself as a drummer, and that’s all you do, then you won’t go beyond that. The same thing as if you’re just a guitar player. But if you start thinking about structure and arrangement and how something feels, then you’re inherently in the realm of a producer mind. I think a lot of people could be really good producers. I don’t think it’s a rarefied. I think some are better than others, but I think a lot of people could produce if they put the energy into it. And I got into it because I was starting to do my own projects that were independent. I was producing them out of my home studio – not that studio, but I had a home studio in Seattle and I had one when I lived in New Mexico, and I’d just be producing it on my own anyway and I often didn’t have a budget where I could hire an outside producer, and I don’t know who I would have hired to do that anyway. I was always the best person in the room to do that job.

But I would always hire someone to mix the albums – I’m not really a mixer. I think that’s a high art form. If you can find a really good mixer, it’s worth it to work with them and have them make your album sound as pristine as possible. But, I think, when I stopped being in a rock band and I started just playing on people’s records, and people would ask me to produce a song and that would turn into two songs and that would turn into an album – that’s kind of how it started. But half of the stuff I produced was my own stuff, or a collaboration with another group of musicians; and half of it were people hiring me to come in and produce their album. Most of the time, I’m also playing drums on that stuff too! Not always – sometimes I produce an album where they already have a drummer, but a lot of the time I end up playing the drum tracks as well.

I think you’ve been on hundreds of albums now, so I guess you’re always busy with this stuff.

I think it’s coming up on a couple of hundred albums, but I’m on thousands of individual songs.

It’s fun man!

I like playing on somebody’s song and adding a little bit of sparkle to it. I do it as much as I can, but I also have to allocate my time to do all this other stuff. Like, I wrote the book, but now I’m editing that music series for the VEVO channel – so, now I’m learning how to edit. Like, I have a guy who’s a really a good editor working with me, but I’m the one who still has to put the story together, so now I’m putting the visual media with the music we recorded and it’s an ongoing learning curve. But the technology is amazing – like how much easier it is to do this stuff than it was thirty years ago. You couldn’t do this – it didn’t exist.

[break for dial back in]

Going back to the book, when you’re living a life like you’ve lived, there must be a temptation to compartmentalise what you’ve done so you can move forward when you need to. Was it a challenge, when you started writing the book, to revisit this period of your life? Did you find yourself reaching out to people to fill in blanks, or did it start to come more fluently as you progressed through the writing?

Well, I started writing the stories in… I’m going to say 2014-15, because I was writing my first book, The Singing Earth, which was about music around the world and, of course, I had to have some stories about the Pacific Northwest music scene. But I had way more stories about the Screaming Trees than I did about any other band that I was in. I wrote one story about Skin Yard, which was my first real grunge band. I wrote a story about the Screaming Tress and a story about Mad Season, and then after that I was writing about music around the world.

So, I had all these stories started, and they were saved as Word Documents that I had sketched out. And then I read Mark’s book, and Mark and I had talked. He had called me a couple of times to ask me if I remembered certain things, like the beer throwing incident, you know like that… and a couple of other things.

We were laughing our asses off trying to remember, it was like “god, that’s not what I remember, I remember this other thing!” So, there was this back-and-forth trip down rock ‘n’ roll dementia, you know, trying to piece together this stuff [laughs]. So, after he published his book, I decided I had to finish mine. And Mark had said that he was like: “you’ve got to finish your version, because you obviously had a better experience”. And I said to him “I was only in the band for ten years” – and remember, the band only existed for fifteen years – so, I was in for the last two third of the band, and all the stuff that happened after. So, my perspective on it was that it wasn’t the defining part of my musical career. It might be the band that some people know me for more than other stuff, but in that period of time, I only played on ten or twelve albums in that whole period.

It was after that that I did all this other stuff. So, I thought that I’d like to write that story like we talked about, objectively but with humour. Because humour was a big part of the Trees. Even if people didn’t see that on the outside, I promise you, all that band did was make jokes and laugh and make fun of ourselves, but also the insane situations that we found ourselves in. Mark encouraged me to write that, in the same way that Anthony Bourdain inspired Mark to write his memoir. Do you know that story?

No, no I don’t.

Well, Mark was friends with Anthony Bourdain, and Anthony apparently told him (Mark told me this): “you have to write your story. It’ll help. You’ll feel better, just getting it out there”. And I think that’s what inspired him to write his own book and… I’m not speaking for Mark; this is just what he told me. And Mark encouraged me to write my version of the band, but you know, I’d already written three books at that point, so I was ready to write. Maybe it took me three books to be ready to write about the Screaming Trees, you know?

It wasn’t the first thing I wanted to write about once I started writing, but once I got into it, it was kind of fun. I put it together chronologically, I remember the humour that we had. But I would talk to the others. I talked to Gary Lee, our guitar player, to remind me of some stuff I talked to Jack Endino quite a bit. Peter Buck was there for a lot of it. He played with Mad Season. He played on the final Screaming Trees album – he was in there a lot. I talked to Mark’s sister, Trina Lanegan, because I was friends with her. Duff McKagan of course, as we’re old friends and have worked together on a lot of different things. And Mike McCready, obviously, because he and I did Mad Season. So, I bounced stuff off people, and all those people read the book (or some version of it), so they gave me feedback and I would ask them follow-up questions. But I didn’t write anything that I didn’t remember. I didn’t speculate – I didn’t write about “maybe this happened…” I didn’t touch that stuff. I focused on what I could remember because I was there, and this is how it went down from my perspective.

One of the things that caught me off guard was the level of humour that was in there. But you really avoided anything sensationalist or salacious, even though with so many biographies there’s that temptation to dwell on that side of things. And it seems so fitting to the Trees is that the humour is one of camaraderie – which really fits with how I perceived the band.

Well, yeah. As far as the salacious thing – Mark kind of wrote that book! That’s like the most salacious book ever written, you can’t top that! So, you have to take a different approach and you have to write with a different theme. So, I chose humour, and there’s a lot of historical context stuff, like here we are at Roskilde and technically we’re supposed to open for Nirvana, but now they’re opening for us, and there’s this whole history of Nirvana opening for the Trees. Nirvana opened for Skin Yard; you know!

Things would reverse and inverse, and that was the way Seattle was back then, just this kind of… you have to have the historical context of things to set the mood. I’m not saying I’m a super-funny guy, but apparently, I have the ability to see things through the lens of humour. Let’s put it like this: humour is tragedy plus time! So, it’s now been thirty years. You can look at things a little differently.

I can see how the story of the Samurai bassist, which had me in stitches – I can imagine how it was incredibly stressful and frustrating at the time, but it’s now this incredible anecdote told with humour and love.

[Laughs] Well, Van’s gone too, so we have to talk about him. Van was an incredible musician. He didn’t go to music school, but he had this incredible intuition how to play bass. His music school, like the other guys, was just listening to records his whole life and just learning how to play like the greatest bass players in history. So, even though that story is about him being insanely drunk and doing insane things, that’s how he was –this unpredictably hilarious… he was an amazing guy, I loved Van Conner… he was my roommate, so…

I do want to say one other thing – I’m not going to write another Screaming Trees book.

And I kept it short. Lanegan’s book is over 300 pages, and a lot of memoirs can be really lengthy, and I thought I’d do the sin of storytelling: 33 or 34 stories (if you count the introduction) – concise, to the point. You don’t have to beleaguer people and pull them through this epic. Keep it short and sweet and I feel relieved that I did it like that.

Something else that really comes across within it, and from the outside it was something I very much believed in, but it’s nice to read about it – is the sense of community that existed in Seattle between the bands. And of course, we knew that Alice in Chains had done those tracks with Soundgarden, and Mudhoney, and heart; and there was Mad Season and Temple of the Dog, but again, it’s amazing that that community existed and I think there was a metal band that gave an interview about exactly this, and how they’d noted the community in Seattle, even though (in terms of genre) there’s such a breadth of sound and style.

I was just reading this quote by Werner Herzog, whom I love – he’s an incredible film maker – and he said “this whole thing, as an artist, is not about one album or one movie or one book or one painting. You build a house, and the house is everything you do. It’s the way you live your life, it’s everything you put out to the world”.

And it was the same in Seattle because, aside from all those bands you just listed, who were all amazing bands, there was also all of this incredible music that didn’t become world famous. There was a really great alternative jazz scene in Seattle, and there still is.

Now the biggest jazz scene in the world is East London, and I always hear about this great stuff happening there, but Seattle had all these great jazz players, like Skerik who ended up playing in Mad Season and all these other cool projects. And then there was hip hop, and it was like this early, cool, collaborative hip hop, where a metal band would collaborate with Sir Mix-a-lot, you know. It was like that, there was always a sense of community and collaboration in Seattle.

Just speaking for myself, it was always really exciting and awesome to see such different bands have such success and watch it happen and buy those records and listen to them and go like “wow!” Like Superunknown– they made a huge leap forward with that record. Because Soundgarden was my favourite personal band. I just loved everything they did, and I really followed the trajectory of what they did.

So, that camaraderie thing was always there. Like, even though we did that big world tour with Alice in Chains – and I did not think that was the wisest thing we could have done – but we still loved Alice in Chains and loved the guys in the band. But the tour ended up being detrimental to both bands, so historically, we look back and go “we shouldn’t have done that”. It wasn’t a smart move, but that’s the decision we all made, and we live with that because it happened.

That’s all covered in your book and what came out of the story was the mutual respect and love that you guys had, which led to stuff like Mad Season happening, the douchebag stage manager not withstanding!

That production manager – he was in charge of the stage, and he ran the show itself. Oh my god, that guy was horrible! He was the worst – like every stereotype of buttrock idiot, he was that guy! I can’t even remember his name – I’ve probably blocked it out!

There’s a huge emphasis on the quality of the song writing and that spoke to me because I’ve found as I’ve gotten older, a lot of the stuff that hooked me instantly when I was younger, I still like it, but it hasn’t travelled nearly so well with me as the music that was maybe a little bit more mysterious, required a little more work – and that’s the music that you always, no matter how many times you listen, you always find new stuff in it. And that’s true of Superunknown and, also, I think Dust – and that’s a large part of the song writing aspect you were discussing, I think.

You know, it’s funny because some people like Sweet Oblivion best, and that’s the best-selling record. Lee and I were talking and it’s about to go gold, like finally – after thirty years, it’s about to go gold! Dust still has a ways to go. And some people prefer Dust and I do think the song writing is more realised and, I think it’s a better production.

But Sweet Oblivion has that lean, hungry, swaggery, young song writer sound, while Dust is like mature song writers thinking about how to make an album. I think a lot of that is George Drakoulias, because he’s a great producer, you know. I don’t think he really produces anymore, he’s a music soundtrack supervisor, but he made some of our favourite records back in the day, so a lot of it goes to George.

But also, a lot of us… all of us were sober when we made that record. Mark was clean, I was sober, Van and Lee were fine, like you know, Lee was never really a drinker or a drug user, so all of us were sober, focused, and that’s how we made that album, and I think it’s reflected in the quality of the song writing.

It’s so subjective what people like best, it’s impossible to say. Like The Clash – everyone says London Calling is the greatest Clash album. It’s a pretty fucking amazing record, but my favourite Clash album is Sandinista,you know – the triple album with like really cool songs. So, it’s subjective.

That’s another great example of an album that took a while for me to love – but this is the thing. Growing up with physical media, you’d buy an album and because you’d paid for it – and it was expensive buying a record – it’d sit there and you’d try, and over time you’d find the quality in it.

Yeah, exactly! And that’s the definition of a classic record – it’s whether it holds up after time and how much time. Is it ten years? Twenty? I don’t know – thirty years? I mean, I don’t have that big of a record collection – most of my stuff is digitised but I still have some classic records from Brazil which you can’t anymore, like they don’t exist – and I have pretty much every record I’ve ever played on. But the stuff that I really kind of cherish, I inherited my grandparents’ record collection, so it’s all like 78s of like Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong and the Duke Ellington orchestra. That is classic, no doubt about it – It’s classic music that is part of American history, but that was back in the time when people didn’t make that many records. You really had to be pretty high level to make a record back then because it was so expensive and just not common for everyone to make a record.

So, what is classic in the 21st century? Man, I don’t know. All the pop music we hear on the radio now. I mean, that’s what surprises me now is how much of the music you hear on the radio is just pop music. You hardly hear rock bands on the radio – it’s very, very commercial, and big corporate media music, that’s what it is. Can that even be classic, just by definition? I don’t know.

From a producer mindset – Dust was like 96 – 97 and it was very soon after that that bands started to write more for the CD format, but that feels more like a vinyl album and one of the things I’ve been enjoying (and there are some really amazing double albums), but what I’ve been enjoying is that the vinyl resurgence has led to bands thinking in the way of sequencing for vinyl. You know, where you have the beginning and end of side one and again on side two – rather than the much longer, kind of 70-minute slog. And that sequencing is something I think you were heavily involved in for the Trees?

Yeah, I don’t know why this happened… I guess because Lanegan kind of delegated authority, like: “you guys do this, I’ll do that”. Like, Mark was very involved in the artwork. He really cared what the image on the album looked like, but he kind of left the sequencing to me and Van. But then, he still had… he’d say “yeah, that’s pretty good, but flip those two songs”.

So, that was something I’d not experienced – sitting in a big mastering lab and hearing the mixes Andy Wallace had done (because Andy mixed both Sweet Oblivion and Dust) and sit there and listen to the most pristine sound… like they say: your record never sounds better than the day that you master it. Because you’re listening to it through speakers that cost $50,000 each. They’re like the greatest speakers ever made, the greatest equipment – it’s all the highest level You can’t buy this stuff at guitar centre. And you go “wow, that sounds amazing” and you feel the flow of the songs and the crossfades and the fadeouts.

It’s a very different experience and it’s an artform to doing that, and yeah, one of the last things Mark and I worked on was I had him sequence this double album that I produced for Peter Buck, Rich Robinson and Joseph Arthur, and I’m in the band too – the record hasn’t come out yet, because of endless delays and the Black Crowes are releasing a new album – but someday it’ll come out and that’s Mark’s sequence. Because he loved the album, and none of us could figure out how to sequence it, so he sequenced it in Ireland and sent it back to me and I was like, “that’s perfect”.

Sometimes you just need an objective ear, and I guess he thought I was objective enough that he thought I could sequence the album.

It is an artform, and it’s challenging because you have to deal with not only the order, but also which songs remain on the album or get dropped into B-sides, so I guess ego can get quite involved.

We had a lot of B-sides for sure, because we would do cover songs for B-sides, and sometimes originals too, but it wasn’t hard to work out if something was pretty good, but not enough to be on the album. I don’t remember there ever being any real arguments about that. We usually knew it was those ten songs or eleven songs. It would be obvious and that would be it.

I worked on an R.E.M. record – UP – and I was in the studio with them from the beginning of doing demos to the completed album, and I think we tracked about thirty songs. I’m not kidding, I remember the number 30, like 30 basic tracks. And there’s only 14 on the album. And they’re all great songs, and I love all those songs, but I remember a couple that didn’t make the album, and I was like “man, that was a great song – where did that go?” They’re just sitting in a vault somewhere – some bands are just more prolific than others and R.E.M., man, those guys could write songs.

The last thing I wanted to ask about – how did you start on this journey of exploring world music, and it’s a really interesting but comparatively rare, I think, in the rock world.

You know, I was in music school in the 80s, where we talked about music theory in the West and how it basically all comes from Vienna – it’s the theory all the classical composers used, and it’s what jazz musicians use.

But there were all these other theories about music, like the way Indian music – they have 24 notes in the scale as opposed to the 12 in the Western scale, and they play the ragas that are the equivalent of a scale, at different times in the day, because they have a spiritual component. It’s the same thing with Arabic music– they have the same 24 notes instead of the 12, because of the quarter tones, and there’s more of a religious and spiritual significance to it and that always stuck with me – like music is not just something that you conceive of to be sold as a product. There’s music that you play because it’s part of your spiritual identity and you have to do it because it’s who you are and it’s your culture and it’s been that way for thousands of years.

And I was getting into this stuff in the 80s, and then in the 90s, everything was being reissued on CD, so I was getting Rave Shankar and Fela Kuti, and I just thought it was super cool. Especially drummers – they’re just keen to embrace world music because there are so many rhythms and percussive instruments that you can use. I think it’s more common for a drummer to get into that stuff than a rock guitarist.

But then, you look at the history of great rock bands, like Brian Jones was into the Joujouka musicians in Morocco, and so was Led Zeppelin; and Paul Simon did the South African stuff, and I met Peter Gabriel at a dinner party at the Sundance Film Festival about twenty years ago. We were seated at the same table, so I got to have an extensive discussion with him, because I loved all the stuff that he brought out on the Real World label, I thought that was the coolest. I mean, I love Genesis and his solo albums, but bringing out other people’s music on a label like that, I thought it was one of the coolest things that anybody has done.

And then, I started doing those trips. I went to Africa. I got to go to Cuba as part of that music groups programme. I was recording and touring in Brazil, and just being in those places, it exposed me to so much other music – being physically present in those countries. Suddenly this whole other world of music is open to you than if I’d stayed in Seattle and gone to the local record shop.

I mean, you can learn a lot from a record shop – I’m not tearing that down – but when you go to a place, it’s a totally different experience. And it’s just naturally in me to do that, so when I went back to school, I knew exactly what I was going to do. I wanted to study ethnomusicology and learn about music around the world. And I was on a really good programme with a couple of ethnomusicologists who taught me a lot about that.

But I think it’s just my musical mind to look through different sounds and mix that together. I mean, you have Daman Albarn – I think he’s into world music, or at least African Music, because he’s spent a lot of time in Mali.

That’s the thing about England. When you’re in the US, it’s a long way to go anywhere, so we’re closer to South America than you are, but it’s still a long way to go. But, if you get on a flight to Africa from the UK, it’s just three or four hours – it’s pretty fast. And the Middle East is right there – there’s a lot of incredible music just right there, like to the south of England.

All of this is to say that I was naturally drawn to that and the more I learned about it, the more I was interested in it and most of the music around the world is played by people for the joy of playing it, not because they make any money out of it. In the Western world, it’s kind of automatically conditioned by capitalism to think of it as something to make and sell. And that’s fine – I’ve done that my whole life – as long as you remember that music, at its foundation, is supposed to be a spiritual thing.

I believe very strongly in the ability of music to transcend boundaries, and I think that’s why I was so interested in your study of world music.

One of the first things you learn when you take ethnomusicology 101 – there’s a theory, and it’s very likely true – that music emerged as a survival mechanism. We were probably able to make musical sounds with our vocal cords – essentially early singing – before we had complex language. And the reason they think that is that music is in the entire brain, while language is limited to two areas in the left hemisphere. So, language is very specific, but music encompasses it all.

And the theory is that somehow, we started singing as a tribal collective, an everybody could learn that melody or that series of sounds and participate in it as a collective group, and probably a lot of that happened around a fire and we learned how to create a community with sound. They’ve found like thigh bones of ancestors that were probably used as rhythm sticks – like hit together to make a rhythmic pattern because it’s the spirt of the ancestors speaking through the bones.

I like that theory a lot and it makes sense why music has such power to pull community together for sure, and all over the world you see music uniting people. In the US, the civil Rights movement is still considered the most musical social movement of all time – there are so many songs and collaborations between black and white people that happened during the Civil Rights movement, and which continue to this day. I think it absolutely does have its roots as a survival mechanism for sure, then language evolved and they kind of go side by side.

One last thing I want to add – the series I’m doing for the VEVO channel – we’re editing the first season right now and it’s everything I just said but condensed into ten-minute episodes. Like we start in the Peruvian Amazon, and we go down. And we go to the Mississippi Delta. We go to Seattle, and we go all the way to the Arctic. That’s the first seasons. Season two, we’re mapping out right now. We’re going to do an episode in Iceland for sure, as I’m going to be touring over there in April and May, so we’re going to go to Iceland as well but that’s the overriding theme in the series. It’s called Singing Earth. You can watch the trailer – it’s up right now – VEVO – Singing Earth. It’s a four-minute trailer that sketches out this first season. But the thing that I learned is that most of the time, music is just a thing that people do to hold their identity and their community together, it’s not like “let’s make a record and sell it!” It’s entirely a different approach, and I’m really excited about it actually. I think people will learn a lot and it’s also really beautiful. The Cinematography. I was there – in all these things, I’m the host, but the guy who filmed it just did an amazing job.

Thank you so much for this amazing interview – it’s been such a pleasure to have this opportunity and I’ve enjoyed talking with you very much.

Thank you, I enjoyed it very much, it was a good conversation.