Always a chameleon, Beck has evolved and matured over the last three decades to emerge as one of the most original song writers of his generation. From the early lo-fi sound clashes of Mellow Gold and Stereopathetic Soulmanure, via the sophisticated eclecticism of Odelay and Guero, to the gorgeous, sun-dappled work of Morning Phase, he is an artist more suited than most to an orchestral overview. Even so, this – the first of a two-night residency at the famed Royal Albert Hall – offers a chance to see this most versatile of performers in a different light, with the bulk of the material drawn from his more understated albums, Sea Change, Mutations, and Morning Phase. It not only makes for a lush, enjoyable evening, but it also quietly reminds the us that, for all the digressions, the core of Beck’s long-standing success is his ability to pen genuine, heartfelt pieces of music that resonate with audiences the world over.

He’s picked the perfect time for it. Despite the Easter weekend traditionally being a washout, it proves to be a glorious evening in London and, as we walk to one of the country’s most famed venues, it is awash in golden sunlight, the building strangely serene despite the bustling city that surrounds it. It seems strangely apt, providing a calm visual companion to the lush soundscapes that Beck has in mind.

Once inside, we take our seats in time for Molly Lewis, who arrives on stage in a striking ball gown. Molly, as she shakily informs us, whistles. It is an unusual performance to say the least, with each piece of music finding Molly whistling over a fairly synthetic backdrop. Despite the applause which ripples across the venue, many seem to be a little nonplussed, and it all begins to wear a little thin some time before the final song.

Not that it’s without its merits for those who enjoy the approach. It takes considerable bravery to step up onto so vast a stage alone, and Molly has a certain charisma and good nature that offsets initial reservations. Nevertheless, with the backing somewhat reminiscent of the canned music one finds in lifts, it feels just a little too much like a novelty act, briefly in focus due to a number of high-profile engagements (not least the Barbie soundtrack), but unlikely to last.

Following an interval and the obligatory period of tuning, it’s time for Beck. With the orchestra providing a brief prelude in the form of Cycle, he affects a surprisingly low-key entrance, strumming the sublime opening chords to The Golden Age as the venue erupts with applause. It’s a beautiful opening gambit, and it neatly sets the mood for an unpredictable night that finds Beck delving into his catalogue to offer up a mix of deep cuts and covers, as well as a few hits – sprinkled like fairy dust across the set. Keeping things mellow, Everybody’s Got To Learn Sometime (a Korgis’ cover from Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind) has wonderful depth, as does Lonesome Tears (from Sea Change). However, clearly aware that the sedate pace of the opening section, which concludes with Wave, cannot be sustained, Beck suddenly laughs “it’s time to lighten the mood”, before launching into the glorious, Latin-tinged Tropicalia – the first sign that, for all his obvious respect for the orchestral form, anything goes this evening.

Following two calmer numbers – a dreamy Blue Moon and a ramshackle Lost Cause – we get another surprise in the form of The New Pollution, complete with grungy guitar and bursts of feedback. Sensibly, during moments like this, the orchestra hangs back a little, allowing a little more space for the band to roam free which, propelled by long-time Beck companion Joey Waronker, they do with obvious glee. Better still, we get a breezy Missing from the glorious Guero (which comes complete with free pronunciation lesson from Beck), which ports the strings across from the album wholesale and has the audience tapping their feet appreciatively.

As promised, the set not only features deep cuts, but also a number of covers, and the next portion of the set finds Beck bringing out This Mortal Coil (“I’m a secret goth,” he laughs) and Scott Walker. For the latter, Beck asks that we indulge him (“think of it as £100,0000 karaoke”), before calmly demonstrating his ability to inhabit the personality of the music he performs. It’s the first of two Walker covers this evening, with both showcasing Beck’s deep and obvious connection to the source material.

Then, at the core of the set, lies the almost unbearably beautiful Round The Bend, which finds the orchestra swelling up to meet Beck’s fragile vocal. A poignant testament to his remarkable song writing skills, it’s a heartbreaking, psychedelic masterpiece that nods to his love of the Beatles without explicitly aping their style.

With so stunning a moment needing space and time to absorb, Beck wisely follows it up with the jazzy, lo-fi Paper Tiger, which meanders gently in Round The Bend’s poignant wake. A necessary palette cleanser, it paves the way for the fifties-style balladeering of We Live Again and, with a further request for indulgence, a cover of Montague Terrace which fits right alongside Beck’s own material as if written for this moment.

With the set nearing its end, Beck returns to Morning Phase for the lush instrumental, Phase, and the life-affirming Morning. Between this and the gorgeous Waking Light, it’s an airy finale that leads to a richly deserved standing ovation right across the auditorium.

However, the orchestra are not quite done, and, with a cheeky grin, they launch into a rousing Where It’s At. Arguably the weakest of the collaborative tracks, it’s the only piece of the night where the strings feel like an embellishment rather than an essential ingredient of the song, and while it’s easy to understand that they’d want to close things out with one of Beck’s heaviest hitters, it’s also interesting to see just how easily such a collaboration could have gone wrong had it not been handled with the rare sensitivity Beck displayed in choosing the rest of the set. Which is not to say this rendition of Where It’s At is not a joy to behold – it is an evergreen classic after all – and it closes out the main set with the audience barely able to restrain their delight.

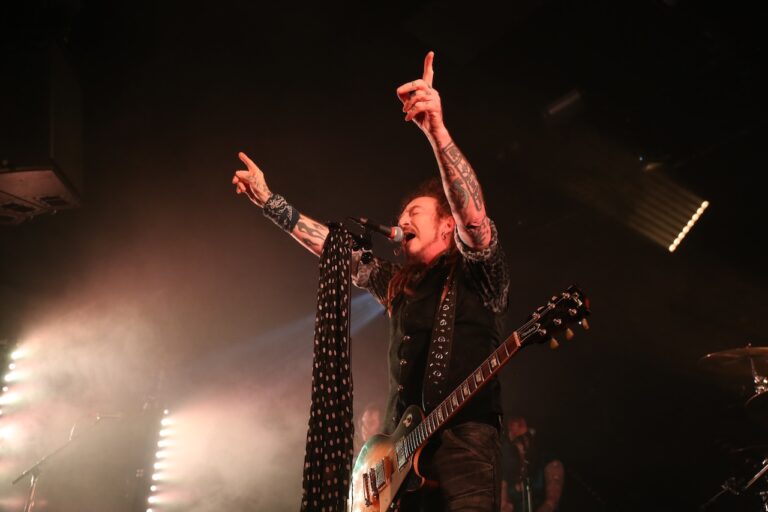

After a short pause which sees the orchestra leave the stage (“an American orchestra takes like 20-minutes to pack up,” Beck marvels), we get a short, sharp band set, bringing the night to a blistering conclusion. As if pleased to be unshackled from his orchestral tether, Beck roams amidst the orchestra’s various instruments (wherein he gives every impression of being a child in a sweetshop), before whipping out an electric guitar to unleash ferocious versions of Devil’s Haircut and the seriously funky Mixed Bizness. Following a solo One Foot In The Grave, all toe-tapping harmonica and impromptu singalongs, a slide guitar is produced for an explosive Loser. With the crowd singing along (and continuing to sing as they exit the building), it provides the night with a gloriously ebullient conclusion.

Orchestral collaborations, when done well, can really bring the best out of a band’s material. Conversely, a poorly thought-out set can result in the orchestra feeling like an embellishment at best and an active impediment to the band’s sound at worst. Fortunately, Beck is savvy enough to focus on those songs that, while not necessarily his biggest hits, have strings in the original arrangement, ensuring that the various elements remain perfectly aligned across the night. Offering up a set that focuses on his mellower material, with just enough curveballs to keep things dynamic, it’s a masterclass that underscores at every moment Beck’s strengths as a songwriter. The hard-rocking band set, meanwhile, provided an adrenaline-packed coda that wrapped the evening up perfectly.

Performances like this are a rare joy and to be treasured. From heart breaking to life affirming, this stunning, 2-hour performance had it all, and we can only hope that a live record of these special shows will follow in due course.