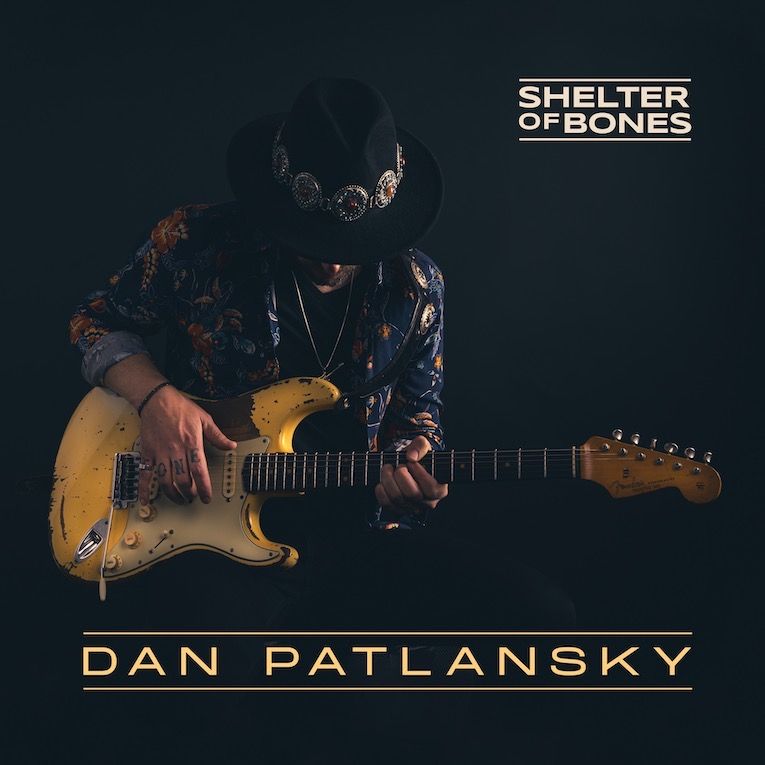

Dear Silence Thieves. That’s where it all started for me. It was the first album I’d encountered from South African artist Dan Patlansky (although it was, in fact, his seventh) and, with its tongue-in-cheek title directly taking aim at audience members who gabble away throughout an artist’s set, I was intrigued before I heard a note.

Then I heard storming single Back Bite, and I was utterly hooked. With Dan playing his Strat fast and loose, the single has a taut, funky vibe to it that, even some eight years later, sounds like nothing else out there. It is a massive single, possessed of an unstoppable hook that lodges itself in your brain, refusing to move no matter what else you throw at it. Yet, dig deeper, and you’ll find that for every track of guitar-driven hard blues, there’s a deeper cut, fuelled by emotion, and showcasing a very different side to the pyrotechnics of the lead single. It is something you notice in Dan’s work, refined on 2018’s Perfection Kills and arguably reaching its peak on Shelter of Bones, a record that saw Dan explore his most personal set of lyrics yet. We caught up with Dan on the eve of his recent UK tour and, as ever, he proved a genial host, taking the time to discuss Shelter of Bones, the impact of the pandemic and his interest in acquiring all things guitar related, demonstrating once again that, for all his remarkable skill, Dan is an artist who plays music entirely for the love of it. His enthusiasm, both on and off record, is infectious – a rare commodity in a cynical era – making any opportunity to catch up special indeed.

Hey how you doing?

I’m good – yourself brother?

I’m good, thanks! it is wonderful to speak with you again after so long. First of all, thank you so much for agreeing to have a chat – it’s great to catch up, especially as you’re back in the UK, and of course you’re supporting a great album.

It’s been a wild ride, yeah! Lots of albums and a pandemic in the middle of it and yeah, I’m super, super excited to be coming back, so thank you for your time, man.

No worries at all. It’s an exciting tour, because you’re focusing on intimate venues and towns where you already have that history, which is really cool. So, how did you land on taking this approach in the first place?

Well, you know, we toured the UK a lot – pretty much this time last year, promoting Shelter of Bones and, obviously I want to come back and spend as much time as I can touring the UK. As an annual thing, at the very, very least. So, when it came to looking at which cities and towns and types of venues, I have very, very fond memories of certain venues, and they tend to be venues that are slightly smaller sized. I believe that the stuff that I’m doing, it’s really built for venues that are intimate, where you can feel the energy from an audience and, it’s like this give and take thing between an audience member and the musicians – 50/50 – and there’s no better place to feel that than in a tight, intimate venue. There really isn’t a better place, and a lot of these towns and venues, I’ve only got fond memories of playing there, so it was almost a no brainer deciding where I wanted to play again and which venues I wanted to return to.

I get that, and yeah, when I think back to the gigs that I remember from being a teenager, where there was no money to go to those huge stadium gigs – I can just remember those sticky-floored, black-walled venues, and they were some of the best gigs of my life!

Yeah! Exactly! You know, don’t get me wrong, as musicians we all want to be playing the Albert Hall or some arena, and that’s awesome. But, when I’ve had the opportunity to play venues like that, and it’s mostly (if I’m honest) as a support – I don‘t really pull arena-sized audiences; it’s a very, very different way of playing and thinking. It almost feels like a rehearsal, with a bunch of energy in the corner of the room. It’s quite difficult to connect in a sense. Whereas, if you’re playing smaller venues, oh man, even if it’s a tough show, it’s OK, because you can see the whites of people’s eyes!

It’s just like you said – some of the best gigs are in small, dingy kind of rooms. There’s just that magic that seems to happen, and I’m a firm believer in the idea that it’s 50 % the band and 50% the audience – that’s what creates a great night of music. It’s that energy snowballing between the audience and band – they shout and give you a boost of confidence, and that makes you play better, it makes you sing better, and it makes you perform better, and, in turn, you get a better reaction from the audience. That sort of music is just born to be in small venues.

Completely, yeah. You did a lot of albums back-to-back – you did two years, two years, two years and then it was four years to do the last one. Obviously, the pandemic was slap bang in the middle of that, so were you, like so many, pushed into having to do things remotely?

Yeah, it’s quite interesting. That album was pretty much ready – we had finished recording by the end of 2019, and the plan was to launch it in the March of 2020 and, honestly, we couldn’t have picked a worst month in the history of the music industry to release an album!

So, we decided not to do that then, and then everyone said the pandemic was going to be a two-month affair, and obviously that was not the case at all. And, because it dragged on so long, you kind of open up a can of worms with the album, because you’ve got this opportunity to listen to it like every day and some days you wake up and think yeah, this is a great album! And the very next day, you’re like “this is the biggest pile of crap that’s ever been put down on tape, and I think we need to start from scratch”. Like we needed new songs and everything.

It’s unnatural to have that much time to ponder upon a record. A record is supposed to be, in my opinion, a little timestamp of a particular time of your life – your musical influences, your song-writing style, your particular direction. That little time capsule of where you are. But, when you’ve got almost three years to mess around with the album, it can get very tedious, and it did. I rewrote a bunch of songs. We re-recorded a bunch of songs. Most of them went back to the way they were – they were fine the way they were, we were just overthinking it.

But some of the changes were good, they were like changes for the good, but I must say, I would never, ever want a four-year period to do an album ever again. Ever. It’s just way, way too long.

You can have way too much time and, when you’re an artist, you can be your own most damning critic and you’re picking up on stuff that, probably 90% of the audience will never hear – for you it’s a catastrophe, for them it’s invisible!

It’s crazy man, so – I’m glad that the world has somewhat returned to something of a normality. It’s kind of back to… almost the other way. I’m not in a rush to say: “every two years, I must release an album”, but it does really feel like it’s time to release something new, because this album has been pretty much ready since 2019 and I’ve been listening to it since 2019, so I feel it’s time for fresh music and a fresh kind of vibe.

As an album, it’s a very personal album, because you’ve got songs on there like Selfish Lover, which deals with addiction and smoking, and there’s a song about your wife being ill, and I was happy to read that she’s recovered now.

Yeah, she’s 100% now, thank goodness, yeah.

So, you have these personal songs, but at the same time, the challenge is to make these things that are very personal to you, universal to the audience, and I think that can be quite difficult.

It is a challenging thing, it really, really is. You know, I had a lot of time… songs like that came about during that lockdown period, right, where I was kind of sitting here in my studio and writing and thinking maybe it would be a better thing to have on the record. Or maybe just refining a set of lyrics. So, it did get more into a personal thing and it’s kind of cool, because I think being a blues-based artist, even if it’s a blues-rock thing, or whatever it is, I think there’s a tendency to go into those cliché kind of lyrical moments of “whiskey and women”.

For me, the guys that wrote that stuff back in the day, that was like honest truth – like them talking about the way they lived their lives. I mean I’d be lying if I said, you know, I lived the lifestyle of, like, Howling Wolf or one of those old guys. I mean those guys were seriously hardcore dudes and I would just feel like a phoney if I got too kind of “whiskey and womanish”!

You know, I still love the blues, and I love the platform of the blues, and how you can mix so many different genres and so many different influences into the blues, and it kind of works. I just got to the point where I felt I really needed to write honestly about where I am and stuff that’s happening in my life. And it’s quite a scary thing because you’re putting your, you know, real personal matters on a record, and there’s a story in the text of the record and all that sort of stuff, and it’s a peculiar feeling, it really, really is. It’s quite strange, but it’s also liberating. I see it as more of a blues-based thing, but maybe the lyrics take it into other areas and, if so (and people feel that), it’s OK, it is what it is. But it’s very, very liberating to do.

I always thought the blues was, as much as anything else, about authenticity to you – having your own voice and considering whatever has given you the blues and whatever will provide catharsis – otherwise, it just becomes pastiche.

Completely.

So, you have the vulnerability that comes from writing personal lyrics and then, the other side of it is that you are an exceptional guitarist, but what I really enjoy about your music is that the skill is not necessarily visible, which is important. You don’t want virtuosity to overshadow the soul.

You know what, the way you put it is the first time I’ve heard it put that way and it’s a brilliant way to put it – you don’t want virtuosity to overshadow the soul of the song.

Yes, as a guitar player, it’s… it’s the first love, it’s the seed of music – it’s the guitar, the tones, and the pedals and all the stuff that goes along with that. So, there is that fine line of going “right, I’ve written the song now, and the feel of the song and the vibe of the song that I want to come across is this…” But there’s always that guitar player that comes out – the guitar player that just wants to play every little gap and make sure that every little nook and cranny in the song is filled with some cool stuff.

But, you know, it was the Dear Silence Thieves album… I worked with a producer who wasn’t a blues producer at all. He didn’t really listen to the blues, or he listened to it, but it wasn’t really his thing. He definitely hadn’t produced blues albums before. He was a rock producer by trade, and more of a commercial rock producer actually back here in South Africa.

On that whole album, we spent most of the album butting heads, especially at the beginning because I felt he was taking the music way too far in that direction, and I wanted to take it all the way in this direction, so we ended up finding this middle ground that we didn’t feel was a compromise, and we were like “OK cool, we’re both happy with the song now and everything”. So, he always said (and it made sense at the time), with the guitar playing thing, it’s the same as singing and the same as anything, it’s got to serve the song, always. It’s not necessarily about whether you can do better licks, or faster licks, but it’s not going to necessarily make sense in the song, and it might overshadow parts of the song, the vulnerability of the song, or whatever the case is.

So, you know, through trial and error, I kind of worked that out first hand. So, when I’m pre-producing stuff in the studio, and I’m putting down solo ideas – killer stuff, like from a guitar player’s point of view, when you listen to it in the context of the song and put almost a producer hat on, you realise it makes zero sense to what’s happening. It’s just making things bleak and worse, and it’s always that realisation for me, and it kind of stuck with me and because when I’m producing the album too, I’m always very conscious of wearing that producer hat and not wearing that guitar player hat in the wrong instances – in the big decision making in where a song’s going.

It’s that David Gilmour thing – you can do so much with surprisingly little. And if you look, even at a solo like Comfortably numb, it’s a masterpiece, but it’s not particularly fast and it doesn’t have that much packed into it, but it still raises goose bumps every time I hear it.

Well, me too. Gilmour is a massive influence, and he was when I was growing up. He was the guy who really got me into playing guitar. When I started getting into Floyd, I remember hearing Shine on You Crazy Diamond and going “damn!” Like, I wanted to be able to do that. It just sounds… it just ticks all the boxes for me. And you’re right, even that solo – all of his solos – none of them are these technical marvels, or anything that probably most guitar players couldn’t play. But it’s the way he plays it, and he wrote the thing! And that, for me, I always say, you get guitar players more like me who improvise on stage, but it would be so bleak if Pink Floyd had a reunion, and I bought tickets and David Gilmour improvised the solo for Comfortably Numb, right? If he did it differently, you’d feel short changed because, as you said, it’s a masterpiece, it’s like a song in itself, that solo. And, you know, that’s why I take so much inspiration from a guy like David Gilmour, even though he doesn’t necessarily improvise, it just serves the song, it creates a feeling. It’s not just a guitar thing. It makes the listener go somewhere, even if you have no idea what’s happening on the guitar. That, for me, that’s the mastery and wisdom that a guy like David Gilmour has always had. It’s not about being a guitar hero, it’s about serving the song. I guess that’s what made him a guitar hero.

That was really interesting, what you were saying about you and the producer on Dear Silence Thieves. I really like that idea of working with people outside of your comfort zone, because it forces you to do things a bit differently. If you’re working with people who dig the same things as you, that’s really great, but it sometimes lets you float in the middle of your range, but if you’re forced to one side, that’s where the cool stuff happens.

Well, without a doubt man! And that was the first time that I experienced that, you know? I remember I would come with a song idea – I’d have lyrics, I’d have a melody, I’d have a riff and, before we even recorded it, like in the pre-production stage, we’d experiment with like a zillion different things within that riff, right? We’d make it super-fast; we’d make it super-slow, we’d change it to disco beat, we’d change it to 6/8 and we’d have all these different feels. And, if you haven’t experienced it before, you get a bit of heart failure, like “what is this guy doing to my song! I’m not a disco guy!”

I remember on that song Back Bite; we had like an ABBA version of it, and I was like “is this guy smoking crack? Surely, we’re not going… has he heard me?” And all it was, and he explained it to me at the end was that well, the chances of us using the ABBA version of the song were almost nothing, but by going there, you collect little gems. Like, “now I’m hearing this at this tempo, I can hear how this would fit”.

So, when you take it back to the original tempo, you come home with this gem that you would never have even thought about before, and I must say, after working with them for two albums, and then taking up the production myself again, it’s one of the things that I’ve always done in the pre-production. It’s so valuable, to really push the boundaries of it to places that you hate! To places where you utterly despise the way it sounds. Sometimes you get nothing, but very often you come up with these great melody ideas, and they really work, and you end up with something unique that you would never have thought about before. So, yes, that butting heads was, as frustrating as it was, it was a fantastic experience.

When I was writing this interview this morning, one of the questions I wanted to ask was about how you focus on Strats because, given how heavy your music can be, I would have thought you might dig some Les Paul chunkiness – that was originally the question, and then when I was listening to Back Bite, I realised that, while at the start you get the heaviness, you get that weird, flintiness that sits between the riffs, whereas with the Les Paul you get a kind of grunt that captures a very different vibe –

Yeah! It’s a good question and it’s the strangest thing. I love Les Pauls, I love it when I hear other people playing them, right? When a Les Paul player plays a Les Paul, it’s like damn! That sounds so good. If it’s in a blues sense or a rock sense or whatever the case is, you’re right, it’s got the girth and that thickness. I see it, in my weird mind; I hear the Les Paul tone as, you know like those bathroom windows that are frosted so no one can see in; it’s opaque, but thick and sturdy and gritty and powerful. Whereas Strats are clear glass – slightly more open and a lot thinner and weaker in a sense.

And you’re right, on certain things, it would make sense to have this humbucking kind of sound just to grind, but you’re right, the Strat, when played with a certain technique, it can sound big, but it’s a different kind of big. It’s in-between the lines, like you just said. It’s got that naturally scooped mid-range, whereas the Les Paul is more kind of even. It’s got a lot more mid-range in it and that mid-range, especially for roots stuff, and especially if you have a Fuzz Face type of pedal, which is also scooped in the mid-range, it really works well, especially in a trip type of thing because it just leaves this place for the voice to sit, or an organ solo, or whatever’s being featured at that point of the song.

But, yeah, I have tried! I promise you, Phil, because I love so many Les Paul Players, so many of them and every time I’ve been in a guitar store, and I’m talking like top quality Les Pauls. I’ve even had the opportunity to play a real ’59 and a real 1960… not at gigs, but just other people’s guitars – but, as awesome as they are, it just so doesn’t make sense to my style of playing.

As a kid, it used to bother me, but the older you get, the more you realise you play in the style you play and it’s different to the style the next guy plays, and you kind of favour a certain instrument, because you know it and it just becomes part of your writing and everything. So, if I write a riff on a Les Paul, it’ll come out way differently to how I write a riff on a Strat, because you have to attack the Strat harder to get that percussive noise, where on a Les Paul, you don’t need to, and it can be a cleaner, more clinical kind of playing of the riff if that makes sense.

I don’t know, it’s got that slightly funky quality to it – especially on the Dear Silence Thieves album, the way the distortion is, it skips over the beat, whereas with a Les Paul, there’s that thick hum that comes between the chords and it gives you a totally different, Alice in Chains-y kind of vibe, but it’s a very different thing!

Yes! A very different thing, exactly, man. Exactly.

So, are you still avidly collecting gear, because I did have a nice mental image of you sat throughout the pandemic scouring the internet for fuzz pedals.

Yep!

I mean, you can’t see it, but I’ve got like a graveyard of fuzz pedals and overdrives. Especially fuzz pedals – it’s such a different beast, a fuzz pedal. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been on tour…

Actually, the last time I was in Denmark, I went to this small little music shop in a small little village, and it wasn’t a cheap music shop, either right? It was quite a high end, boutique type of shop. And I didn’t go in there for any particular reason. We just had the afternoon off, and I thought “let me pop in”… and there were these high-end Danish fuzz pedals, and they cost the bloody earth! I plugged one in – not on my guitar, just through a random guitar on the wall, through a random amp in the shop; and I plugged it in, and I was like “aaaagh, this is the best fuzz I have ever played in my life!” And I bought it there and then and, that afternoon, we got into the venue to soundcheck, and I put it through my rig, with my guitar, amp, and pedal board, and it was… not great! It wasn’t fantastic and it was the last show of the tour, and I was like, just get home and experiment and guess what? It’s now sitting in the graveyard under a few millimetres of dust, and I can’t sell it because no one knows what the hell it is!

So, there is still a bit of that going on. I bought a new Strat recently, this Daphne blue, kind of custom shop Strat. And I wasn’t in the market for a Strat at all, because I got a master-built Strat for me, as all my old Strats were falling apart and impossible to tour with.

So, I got my master-built Strat, built to my specs and delivered in 2019. I hardly got to play it before the pandemic, but I played the life out of it during the pandemic. Brilliant guitar, love it, love it, love it. Then, Fender booked me to do a custom shop night to demo some guitars and I had 25 custom shop Strats I was going to demo. And it’s quite a rare thing anywhere in the world to demo 25 custom shop Strats, one after the other, and get to compare them. But the whole point was I was being paid to do this and it was a live stream, and there were people in the audience. So, they passed me this Strat and it just blew my hair back!

At the end, I knew that it was a want, not a need. I’ve got a killer Strat, but I couldn’t sleep for about a week and eventually phoned them and asked if I could do a deal in a payoff sort of scenario, and they were kind enough to do a deal, so here I am with yet another guitar, but it’s OK. It’s a truly fabulous guitar, but I have slowed down a little bit after that, because I felt very, very guilty for buying a guitar I didn’t necessarily need. It was a want.

So, I do find it goes in waves and suddenly, I’ve got this itch to get a new acoustic guitar or whatever! But it’s a good place to be, where you’re kind of happy with your rig, which is rare. It’s a rarity where you love the guitar, the pedal board, the amp, and the cab – it’s like… I’m there now and I’m just going to ride that wave as long as possible until something changes.

Until someone puts another boutique pedal under your nose?

YES! Like “aaaaaah, this is what I’ve been waiting for my whole life!”

This is what pedal makers do. They’re evil!

I always feel it must be kind of weird coming to the UK where you’re playing these gigs where the distances are just tiny in comparison to South Africa – how do you find the differences in the crowds and the tour organisation outside of SA?

Well, the first thing I noticed from way back when I first started playing shows in the UK and Europe is almost the musical education of the general audience. Because there’s more of a music culture, compared to SA, right? Like going out and seeing a band is somewhat part of your culture. Compared to SA, it’s massively part of your culture. Here you’ve got to bribe people almost to buy a ticket, get in their car and drive somewhere. God forbid they’ve got to drive somewhere and pay money to stand, you know?!

But, because there’s that heritage of music in the UK, I find that the audience themselves are far more educated in the music they’re listening to. If you’ve got a blues crowd, they know their blues a lot better than your average South African audience will, which is daunting at first, but it’s a real pleasure to play for. You can take the set in certain areas where maybe a South African audience; I’m not saying all of it, but the vast majority; wouldn’t get musically and vibe-wise. So, that was the biggest difference I find.

I also find the actual industry itself in the UK – there is an industry. There are steppingstones for an artist to grow. So, like, when you start out you can go do tiny venues for 40 people, then in most cities and towns, there’s a step up, like 100-120 and then a step up to 2-250 and there’s all these venue sizes all the way up to arenas. So, you have those steps, so you can take baby steps up.

In South Africa, there’s a bunch of places where there are 40-50 people, there’s far fewer places that are 100-120 and then your next step is like 500 and then, your step up from that is 8000. We don’t have that industry; we don’t have the steppingstones. We don’t have that. And then, obviously on the travelling front, it’s… the UK is a pleasure man. I know we’ll land in London on the 11th and then, when I speak to people and they ask where we’re playing the first show, it’s in Glasgow, right? And they’re like “Jesus! It’s so far!” By South African terms, it’s what? A 7–8-hour drive? That’s OK. You leave nice and early in the morning. It’s not a problem. Some of our drives here are 18–20-hour drives, from one side to the other, those do take it out of you.

But that’s why I love the UK! There’s a scene, I find everything relatively close by, even if it’s London to Glasgow or something like that.

There’s a scene, man! There’s a scene, full stop!