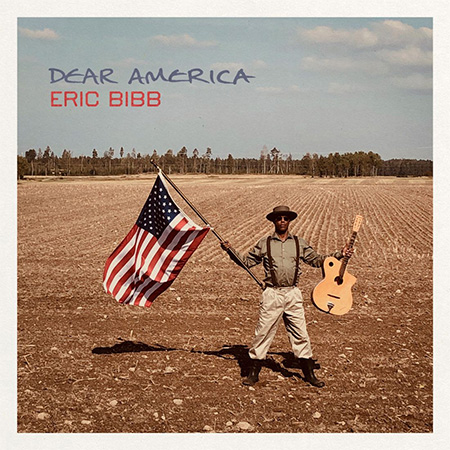

Although I do not tell Eric this, he was one of the first blues artists I embraced as a teenager, thanks to an acoustic live performance given to me by a friend. What struck me then (and what has remained with me since) is how engaging Eric is, not just as a musician, but in the way he speaks to the audience between songs. His style is so easy and unforced, but then there’s the music – raw and from the heart – a characteristic that remains on superlative new album Dear America.

Eric Bibb in person is no different. He speaks softly and with great poise, and yet what comes across most clearly is his great love. Love for the blues, love for America and, of course, love for humanity. He speaks with hope and compassion, not bitterness, and you get a clear sense of how much of himself he invested in the songs that make up Dear America. A gracious host, as you will see, he takes his time in answering each question and, in so doing, provides a good deal of the back story behind one of the year’s most inspirational albums.

A tiny bit of background, you’ve just signed to Provogue – how did you end up on that label?

Well, part of the decision was made for me in terms of needing to find a new home because my dear friend at Dixie Frog Records, Philippe Langlois, retired and sold the company on. He thought it was maybe a moment for me to make an arrangement, here there would be even more spreading of the Bibb word [laughs]. So, he just wished me all the best.

So, I had a chance to open for George Benson on four UK gigs, including two at Albert Hall and at one of those Albert Hall gigs Ed, the owner of the Mascot label, was in the audience (because George is signed to Provogue) so that was probably what got the ball rolling. Then, it probably didn’t hurt that, on a blues cruise (Joe Bonamassa’s Blues Cruise), I met both Joe and Eric Gales and basically asked, even then, if Eric would join me on a song on my new album and he said “sure, it’s gonna happen!”

So, I think, quite a few elements contributed, but I think it was mainly when Ed saw me at The Albert Hall.

Obviously, for so many musicians the last year and a half has been a nightmare in terms of being able to play, and even to record, so could you tell me a little about how you set about recording this album?

It was before Covid. Many of the songs were written before Covid, so they even have some kind of prophetic vibe to them, interestingly enough. We were happy to have been able to record the New York sessions, just before everything shut down and that was just a huge blessing and a wonderful experience.

So, yeah, I record whether I have a deal or not. That’s not what prompts me to record. So, we basically had the record well under way, if not finished, but the time the Mascot deal became ink on paper.

When it comes to the record, one of the many things I particularly enjoyed, was that it feels (to me at least) that it flows like a live set. It starts with you playing very raw and the band don’t really appear until the second track – when you came to put this record together (and I know it’s different for every artist), but that vibe, was that planned from the start or something that emerged once you had a few tracks recorded?

Exactly that – the latter is more accurate but, you know, all through the process I play around with set lists – the running order. As soon as I have enough songs for an album that I think relate to each other in a groovy way, I start fooling around with sequencing. I find that really enjoyable.

It obviously changes over the course of the development of the record, but it’s interesting to look back at your first choices and see what stayed the same. And really, of course, you could call these albums that I’ve been working on recently “concept albums” because I’m a child of the sixties and I love that whole idea of telling a story in several songs. So, this was definitely a narrative story, and I wanted to make it all kind of fit together into a “Dear America…” letter, you know.

I love that Idea. I grew up on the great prog records – Pink Floyd and that sort of thing – and there’s an unsung artistry because you have all the tracks laid out and, of course, there are many different orders you can take, but in the end, it becomes a very personal journey for the artist to make the record in that way and present it to their audience.

Very true. It’s a very important step and your experience of any individual track… (even though people will definitely experience it in that way with all these streaming platforms where, you know, you pick a song as opposed to running through the whole album). …But, nonetheless, it really does influence your whole way of (if you can) objectively seeing your work. The running order will really colour your impression of the work as a whole, so yeah, it’s very important and, like I said, for me: enjoyable. And then there’s the musical thing – not everyone listens sequentially, but it’s nice to have a segue from one song to another that really is, in itself, tantalising.

Yeah, and that’s one of the things – the album ebbs and flows beautifully and you’ve got some longer tracks, and then something very short like Tell Yourself, that feels like it splits the record in two, vinyl style… I love that!

Yeah, yeah, yeah – it’s true. It’s true and there is a vinyl version of this record and, for me, like I said this whole business with telling a story and having a beginning, a middle and an end: you start to see the work as a whole. At a certain point, of course, individual songs make up that whole, but you start to really see it as an opus, you know.

And I read a lot, so I’m really at that headspace of how you tell a story and how you keep a listener’s attention. If they do listen to it in the old school way that I do, which is album-wise… I listen to albums!

I’m the same – the downstairs of my house is a testament to that!

Vinyl?

Quite a lot of vinyl – more CDs though.

Same! Yeah. I have more CDs these days than vinyl, but we’re going to have to start buying up the available CD players, whether they’re new or old, because they’re phasing out. Some shops don’t even sell them. It’s crazy.

I know – I teach, and always the students laugh at me because I’m excited whenever a new record arrives and they’re looking at me like: “what’s that?!”

Yeah, it’s crazy.

But you’re right. For me, the whole journey of making a conceptual record is really interesting. And one of the things I’ve found is that, when you’re making a record like that, the music and lyrics feed off one another. But then I’ve found you come back, and you want to tweak the lyrics here and there to tell the story in the way you want it to go. So, when you were writing this album, did you have a very firm idea of the letter you wanted to write, or did it become more organic and fluid as the sessions went on?

Certainly, again, the latter. I didn’t revise the lyrics after the songs were written to conform to some kind of umbrella idea. That did not happen.

I kept writing songs and, somehow, intuitively, I must have known that I was heading in a certain direction. And when the song “Dear America” came along, soon after that, it became a working title that stayed. And, having committed to that much, I think the songs that followed, and I don’t remember the order in which they were written, may have been influenced by that decision. But not in any kind of hard and fast way at all.

Like I said, I guess I was in a certain zone, with certain issues and subjects really capturing my attention, you know, beyond song-writing, so that just became the well into which I was dipping for material. And, you know, there were more songs written and recorded than are on the album, so you make certain selections, basically, trying to tell the story in the most effective way, without too much fat on the bone.

In terms of developing any record that deals with socio-political themes, there’s a very fine line between sharing an ethos and allowing the listener to come to their own conclusion (which I think, you know, you’ve absolutely done) and preaching… which is not the case here, but it is a challenge, and it is something that’s quite difficult to do. Is that something you’ve found when crafting the lyrics for these songs?

Well, I’ve had experience before this record, of course, commenting on contemporary circumstances that have historical roots. That’s been a kind of theme to a lot of my writing through the years, so I was not a newcomer to that.

However, as you said, and I’m glad you’ve brought up this point, I’ve been sensitive to the whole challenge of not being preachy, even though I sometimes inhabit the personal of a preacher. I feel close to that tradition enough as a storyteller to use that kind of approach. However, there are sermons and sermons and what I like to do is completely avoid an attack kind of energy in my songs, because I don’t feel that that furthers the conversation, which is ultimately the goal of writing those kinds of songs. You want to encourage people to take a second look, a third look, a deeper look at some issues that are, perhaps, really uncomfortable, but which are going to become even more uncomfortable if we try to avoid confronting it in an honest way.

So, I’m used to not only, when it comes to so-called socio-political issues, but even core-belief sharing – it’s something that, depending on the language you use, and certainly if you have a kind of gospel inflection in your lyrics and music, you’re drawing on a language that might not be somebody’s language of choice when expressing spirituality. I tend to like using old school gospel language, but in my own way, meaning that it’s not a fire and brimstone kind of approach. I lean on the newer testament [laughs] and the message I’m really trying to convey is, first of all, one of hope – there’s a reason why I think it’s important to look at these things, because I think there actually is hope for a better world in doing so; but, by claiming your own beliefs, you try to also be aware of being inclusive because you don’t want to end up alienating somebody who might not be able to appreciate or take in a song that’s too far away from their own ethos. So, it’s a tricky thing, but I think you get better and better at walking that thin line the longer that you do it. So, yeah, I’ve been doing it for a while.

For me, listening and going through the album, I found that White and Black was a perfect example of that, because it didn’t feel didactic – it felt more like an exploration of how everybody looks at the world through their own unique lens, which is a human condition, I guess.

Absolutely. Listen, tribalism is as old as Methuselah and it’s like OK there were reasons – logistical and survival reasons – that those attitudes persisted, but we’ve come to a point where it’s really self-destructive to be so tribalistic in these times, when all the human resources available to us are needed if we are going to actually survive. We’ve fucked it up so bad, so one of the practical things that I think about is that, not only is it devastating to be excluded because of your skin colour or gender or whatever, but it’s an incredible waste of human resources. You judge somebody, you knock them out of the ballpark before they’ve even entered and you have limited your access to something, perhaps, incredibly valuable to everybody. This is so A-B-C basic, but it’s amazing how we persist collectively. Are we that blind to just… you know, it’s impractical. And other things as I said. It creates a lot of suffering, but it’s also like shooting your self in the foot, you know.

The album as an emotional journey, and obviously I’m drawing on my own interpretation, but it draws you in and has quite a dark core, dealing in (including other things) historical horrors like Emmet’s Ghost, but the overarching vibe is one of hope and towards the conclusion we have Talkin’ Bout A Train Parts 1 & 2 and Oneness Of Love and the one message, I think, for me, that would sum up the album is that lyric: “everything can change if we believe” and, as you said, that’s the hope there.

That’s a very good assessment of the intention. Because, I really didn’t want to pull any punches, but at the same time I wanted to try to invite the listener into listening to material that wasn’t necessarily comfortable. But musically, I wanted it to be so attractive that you would stay with it. I wanted people to feel the warmth and the love that I feel for America – as it’s really kind of presented in a very kind of whimsical way in the first song.

When I think about American culture, you can talk about a lot of things, you can talk about the gun culture, you can talk about the racism; but you can also talk about the incredible music that has come out of America, not least the African American communities. But food and music are something pertaining to American culture that the whole world is aware of and appreciates.

So, it’s like, this is going to be a heavy album, but let’s just start out relaxing into what’s common to us all and groovy and American [laughs] and then take it from there. So, yeah, I mean, I feel like I’ve gotten help from sources seen and unseen to create this work with my producer that gets the message across and deepens the conversation. It brings people into an enjoyable musical soundscape – all of those are gaols and to do it in the way that we’ve done it and have already the kind of feedback that we’ve gotten, I can’t tell you how gratifying that it is.

For sure, there’ll be people who react in a negative way to certain songs… for sure. There have already been a few of those kinds of remarks that have surfaced. But those are few and far between. Mostly it’s been fairly unanimous, it’s a deep work that really deserves a wide audience and that’s as good as it gets from my point of view.

Just as the emotional journey is very rich and allows room for interpretation, the musical journey is interesting too, because you have a very rich range of influences. Listening to Talkin’ Bout A Train Parts 1 and 2 – you’ve got some scratchy blues, what sounded to me almost like a hip-hop influence in the way the drums roll, and then into some funk and groove in the second part – it’s a lovely mini-journey on its own.

That is the genius of Glen Scott, my producer, who sees possibilities in my songs that I never dreamed of until we’ve finished and I realise that it was a springboard for a certain type of exploration that he imagined and carried out. And it’s a process where we have back and forth all along the way – things get added or subtracted or whatever – but, that’s one of my favourite tracks, the two of them, and yeah, what can I say?

The influences are real influences, we didn’t do anything because we thought it was hip or trendy. What we put in there are our pet sounds which, like you say, are from the scratchy country blues; through a kind of smoother old-school, but modern approach to soul music; through Caribbean type of bounce to certain things; country influences – it’s all stuff that, for me, I’m not even…

I’m tired of splitting up genres, I think that kind of segregation is outdated. I think we’re all cross-pollinating and I understand why, for marketing purposes, they’re so rigid, but more and more I think musicians are going to find that they’re not going to play along with that, and they’re just basically going to make the music that’s in their hearts. You know, if it’s a country album where you want to make every track sound like it comes out of Nashville, OK; but you might want to really take a left turn. Prince was a great example of someone with that kind of freedom built into his marrow.

That’s an interesting point that you make – if you only listen to one kind of music or only want to play one kind of music, you’re constraining yourself. But if you have a passion for music in all its forms and a love for it, you can create albums that run the whole gamut of emotion and style, but it can still feel coherent.

The thing is, what I’ve noticed is that that kind of eclecticism is probably natural to many more musicians than express it openly in their recordings. I think a lot of it has to do with your position in the industry, I’ve noticed that well-known musicians who have high celebrity and high sales are, perhaps more, or at least going forward are more able to be experimental and call the shots. Joni Mitchell is an example of somebody who called her own shots a lot.

But I think, when you’re starting out, you want to get on board, you want the record company to sell a whole bunch of records and you play the game and you limit yourself so that you can get on to certain festivals that are genre orientated. I’m called a blues player and I love the blues – the blues is part of my rock – my holy rock of ages foundation – but it’s not exclusively what I play. I’ve been influenced by everything from modern jazz to impressionistic orchestral music from France to West African choral music and all of that, sooner or later, just had to come into the picture. To not be able to include that would have hurt me artistically.

And, when it comes to bringing in guests, you’ve got a small but very potent group of artists who came to join you. How do you make the approach to people? Do you have a song where you hear them, or do you get to talking and then bring them in on the project?

I’ll give you an example, or two.

I knew of Eric Gales before I heard him play. But then, I heard him play, live and in person, up close, on Joe Bonamassa’s Blues Cruise- and we were both artists on that cruise – and my wife showed me a little film that she made of Eric standing on the upper deck checking out my set on the lower deck and dancing along to it and I thought “oh, that’s a good sign!”

Then, I saw Eric’s set and was completely blown away. So, the next time I saw him, I walked up to him and said: “man, listen, I’m just knocked out by what you do, and would you consider being a guest on my next album?”

And he says “it’s gonna happen.”

And that was the first thing he said to me: “it’s gonna happen”. And it did [laughs].

And we had a song that we knew we wanted a killer blues guitarist featured on it and Eric was obviously the only person on the list and we got him. And we knew we wanted… my producer had said to me years ago: “Eric, one day we’re going to get to New York and have an ace rhythm section and we’re going to cut some tracks.”

I think we had a couple of drummers on the list – maybe Gadd was on the list, Jordan was certainly on it and Steve Jordan ended up being the drummer. Then, Tommy Simms is an amazing musician whom I’ve worked with before in Nashville.

Lisa Mills – I met her at a festival in Norway and when I heard her, I just thought “oh wow! This is something!” And she was playing everything from gospel tunes to country blues – playing and singing – and she really knocked me out. So, after the gig, we were in the green room and I just said: “hey, Lisa, wonderful! Can I have your details and maybe we’ll do something together.”

And then, during the development of the album, we came back to a song that hadn’t really been earmarked for this project – The Oneness Of Love. We had a second look at it and thought it was a good song to include and then Glenn said: “this is a duet man!”

And I said: “Hey, what about Lisa Mills?”

And he said: “hmmmmmm!” and we made that happen too!

The whole idea of collaboration is just great – when you collaborate with someone, they can take a piece of music that you’ve made, and they can take it off in a totally different direction than you ever expected and yet you feel that it’s right and it’s there and it’s really exciting…

This is true, and this is the beauty of great collaborations. One and one makes three, because there are unpredictable things that happen when two energies, like you say, coalesce. It happened on so many occasions with these sessions. It’s not like we sent out the tracks to everybody before. That wasn’t the usual way we worked, certainly with the instrumentalists. We just asked them to show up in the studio and took it from there. So, yeah.

Probably, one of the bits that I really enjoy on the album, is that it feels like everyone’s really enjoying the process and you can feel that. Especially on, I think it’s Love’s Kingdom, you get that snippet of studio chatter and laughter, and that cements that feeling.

Yeah, we had a ball. It was logistically challenging to bring it all off. It wasn’t a label driven thing. I didn’t have a deal in place before those session took place. We just knew we had a great album coming down the pipe and we weren’t going to spare anything that could keep it from happening. So, we were dreaming big and somehow, we had a great team of people helping and we were able to pull it off. It really was that much fun; it was so exciting. I’ve been touring, you know, but I hadn’t been touring in the States for a while and I hadn’t been to New York for a while and the idea of returning to New York to do this pivotal album with that subject matter was just so hot, you know. And we pulled it off!

It’s wonderful, I really love the way it feels like a very personal address to a country that you obviously love, yet you’re not afraid to hold up a mirror to flaws both internal and within the country in the hope that things will get better.

Yes, one must always hope because otherwise why bother? You know, just take morphine and die! If it’s not going to get better and if we’re not going to continue as generations before us have done, facing hard times and still holding up the banner of peace and love and justice. People have died for this for millennia, so I guess that’s part of the school of life. So, having felt that I had the tools to communicate my take on things and knowing that that’s really what keeps an artist alive as opposed to just robotically being an entertainer – I knew that we had to keep it real, and hope is a part of what artists are supposed to keep alive. I just think that’s our raison d’etre

And ultimately, I think, that’s part of the point of the blues. It’s supposed to subvert whatever’s making you sad, and whatever’s making your heart heavy and turn it into something that’s productive, that’s positive and hopeful.

Absolutely, good point. It brings to mind John Lee Hooker and Santana’s The Healer. You know, the thing is, when it comes to this blues music, this African American concoction that has healed the world and united the world. Among other things, it’s not only groovy stuff that you can dance to and heal your body. It’s a survival tool on a psychological level because it’s a way to use humour and irony and protest and, you know, funky stuff all together to basically belittle the oppression that is really looming so huge in your daily life. But you found something else and the fact that people back in the twenties and thirties were being lynched and their whole lives were based on subjugation, to actually be able to let loose and make groovy music that made you able to work another week from sunup to sundown.

It’s an amazing survival tool and the gospel part even more so. It’s kept a whole people from going under, it’s just a fact. And, in addition to that, it’s been exported to the whole world and the whole world enjoys it and are healed by it and it’s really brought people together. It’s brough together a whole load of music lovers who are connected by loving a certain exponent of culture that was really, at one point, very local man. It’s an amazing story. I could go on!

It’s such a powerful thing and the ability to bring together of all cultures and languages, it’s beautiful.

Yeah! I live in Sweden, and I was in the church rehearsing with a gospel singer years ago. A friend of mine also from the States, who had also lived in Sweden a long time. And we were in the basement of this church, and we looked on the wall and there was a photograph and it looked like there were brown people in this photograph.

I came closer, and it was the Fisk Jubilee singers from the Fisk institute – the college in Tennessee, one of the earliest black colleges. And in 1893 or 2, the Fisk Jubilee singers had gotten on a boat and sailed to Europe. They had sailed somewhere and began a tour that took them all the way to Stockholm, at the end of the nineteenth century – amazing!

This music has been, like I said… it’s had wings for more than a hundred years and it has spread – there are gospel choirs in Sweden, there are gospel choirs in Slovakia – wherever you want to go, there are gospel choirs in Uganda – it’s like “woah, man!” [laughs]