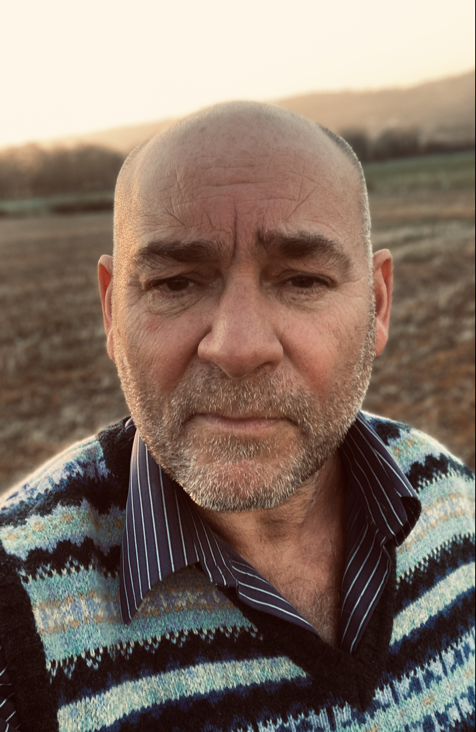

The latest album from JTQ, Hung Up On You, is an absolute treasure. A fast paced, wonderfully organic album that embraces everything from punk to acid jazz, via pop and psychedelia, steadfastly refusing to be cornered at any point. It is a delight and so, when I was offered the chance to speak to its author, the similarly ebullient James Taylor, I gladly jumped at it.

From the outset, you can feel that James lives for music. Give him a topic and he runs with it, throwing out references with all the excitement of someone entering the studio for the very first time. Open minded and with an infectious enthusiasm for his art, you quickly realise just how much of his personality is bound up in this vibrant, joy-fuelled album, and it’s just a pleasure to spend an hour with him discussing its creation.

The first thing I’d like to ask about is… this album surprised me because a number of songs have this punk energy, and I’ve always thought that the term “punk” is a red flag to a certain demographic…

That’s right

It’s almost like it’s the victim of its own kind of early publicity, combined with a sort of antagonistic attitude towards other genres. But the punk bands you reference – The Undertones and The Buzzcocks – are really musical, but that fact often gets shunted away by the terminology. So, I wanted to start with that – bringing punk into a band that started out with a much more jazz fusion background.

Well, you say that, but the first single we released was a tune called Blow Up, which was very punky really. And John Peel picked up on that straight away and played it every night for a year – for the last half of 1986 and the start of 1987 – he played this tune, Blow Up, which was drawing from punk. Even though it was a Herbie Hancock tune, there’s no way you could describe it as “jazz” or “fusion” or anything like that. And the first few JTQ albums, on Eddie Piller’s independent label, were sort of mod-punk kind of… We recorded them in a kind of railway tunnel and they’re pretty bloody lairy!

And the Prisoners, my first band, was pretty rocky as well. So, also, I worked a lot with Billy Childish and we used to tour a lot, The Prisoners and Billy Childish – we used to tour around Europe together. I’m talking around 17-18 years old. So, that’s in my DNA – that’s really in my DNA. And then, I moved into this sort of jazzy arena with my music and signed a big major deal and started playing places that were supposedly a bit more musical and salubrious, and that was OK.

Then they formed this scene, they called it “acid jazz’, and that was pretty… I mean jazz in London at that time was fucking awful! It was the most conservative, snooty, boring, awful stuff. And we came along with acid jazz – us and a few other bands around us – and it was much more working class, and street. And some of those bands got bigger, like Jamiroquai and some other bands like that, but it was much more… It was a bit more Essex I suppose (I mean I’m Kent, but…)

But that was exciting, and you could do it in a much more rock ‘n’ roll way on stage as well. So, we’d do big venues like the Brixton Academy or the Academy in Manchester, and get thousands of people in there, jumping up and down and going nuts. We’d do Glastonbury and get the same thing. And people would say, “well this is a jazz band!”

And we’d say, “well, sort of…” You know!

But then they’d put us onstage at jazz festivals alongside Miles Davis – that’s where it got confusing! And those audiences were very unsure and ambiguous about us. Some loved it and some didn’t. And now, as a sixty-year-old, I’m playing Ronnie Scott’s and I’m seeing this new wave of musicians coming through out of the music colleges, really steeped in sort of Frank Sinatra conservative jazz. It’s just so dull! It’s like the end. Even Miles Davis was saying “this is boring as shit; we’ve got to stop this!” He went on telly and said that you know. So, that whole thing is massive, because of its conservatism. I see it as quite a right-wing thing, quite a conservative sort of thing.

I mean, I always thought the punk rock thing was extremely healthy and very passionate, and it was for the common man. It was just really honest, and there’s something so alluring about that. I’ve done forty years in the music business and to see something that is what it says it is, and does what it says on the tin, it’s pretty bloody amazing.

Anyway, I was working with The Prisoners last year, and I thought, ‘god this is exciting!’ I was enjoying it so much that I wrote a load of songs, and they didn’t want any of them [laughs].

So, I had all these songs, and I got my band – a jazz band – and played these tunes and we just fucking loved it. They loved it. They so enjoyed playing it that we went in the studio and had an absolute blast. And that was the album.

But then, of course, we had to figure out what we were going to do with it. The next week we were going to be at Ronnie Scott’s, and it was going to be so strange. And we have already played some of those songs at Ronnie’s, and they just sit there with their arms folded! At the end of the first song, Hung Up on You, they don’t clap. They just look at you because it’s like heresy [laughs]. But there’s something pretty amazing about that.

Ronnie’s is a tough gig, because you go out there armed with all your clever jazzy licks and try to blow the roof off. And you can do that, but the challenge is to somehow alter people’s perceptions a little bit. And this album is something for me to get my teeth into as I head further and further towards shuffling off the end of my life.

There’s something still really new and exciting for me, and for my band, and hopefully for listeners. Why not, you know.

You see this in pretty much every genre, whether you’re talking about heavy metal or even punk itself – you listen to those early records and they’re so exciting because they’re really pushing against the limits of what’s acceptable. And even those early Miles Davis album, they’re teetering on the edge of acceptability – they’re so raw and exciting. And then the next generation comes along, and they take the little bit that they revere about that, formalise it, and then you get that very conservative approach.

Especially in heavy metal!

So, everything starts to run on these very well-established lines, and you lose something through that.

Led Zeppelin were trying to emulate blues artists. It’s a blues band for fuck’s sake. So, they take the weedly bit of Jimmy Page and then add some horrible, Ian Gillan type vocal, and you end up with something really rank – those are the bits you’re supposed to ignore, mate! [Laughs]

But yeah, I agree, things get diluted and twisted into pretty much what the industry finds palatable. I’ve been making records for ten years now for Audio Network – a company that sells music to advertisers. And I present them with a lot of material, and they’ll say “yeah, this is good, we want that, and that…”

I presented them with this and they said, “we don’t want it!” [Laughs]

And I’m thinking “no, I bet you don’t…. but I bet you people would like it!”

But anyway, this is the first time I’ve put a record out myself for a very long time. It’s exciting. It’s really exciting. Let’s see what happens!

The flip side of all this is that genres are really boxes for the audience, because all of the musicians that I speak to – the ones I like the most – they couldn’t give a toss about genres. They’re so interested in music in its entirety. And that’s what I can hear on this album. It’s pulling from so many different places that it’s very difficult to put a handle on it, and that’s what I really enjoyed about it – it flows across a whole variety of different things.

Yeah, and my radio plugger, he says to me, “that’s the problem with it, I can’t position it, it’s confusing the hell out of people!” And I thought that might happen, because the industry is very uncomfortable with what you just described.

I mean, the next album I’m making is a classical piano album, how’s that going to go down? [Laughs]

But yeah, if you’re into music, as you say, you’re into the whole bloody thing, and so boxes and all of that becomes really frustrating. Once you start pushing against the edges of those boxes and actually completely breaking the boundaries, people go, “well, what now?”

But Acid Jazz was that. When I said to you that jazz was a boring conservative thing and we sort of muscled in and did, sort of, Jimmy Smith kind of aggression, mixing a bit of stuff that would make it palatable to John Peel and Giles Peterson, that’s a pretty weird mix. And that’s an interesting place to be.

John Peel was amazing – he got this, I think, more than any other DJs I can think of. He introduced me to so much stuff, growing up in the 90s – you’d get The Undertones and then you’d get Napalm Death. It was brilliant. But so few people are willing to take those chances, and they’ll go with what they believe will be palatable rather than their own instincts, and it’s such a shame.

It is a shame, but that’s where the coal face is and that’s where the war rages, as it were. And that’s where I want to be. What isn’t a payoff is that you end up playing in front of not many people [laughs].

But, you know, there are things you can do if you want to be massive – there’s things you can do, and it will probably work – the chances are you can make it work. But you’ve got to hold your nose while you’re doing it, and I can’t do that with music. It’s much too an important thing to play games in that way. Why? So, you can make money? What are you going to do with the money? Pay for a psychiatrist to help you out of the depression of doing something that you hate so much [laughs]. You’ve got to do what you like, not just what you think people will like.

Do you know what I mean? [Pauses] Yeah, I think you do know what I mean [laughs].

I’m happy, put it that way. I’m excited about my music, and I’m sixty! So, that’s… getting old is no bloody fun at all. Even gigging and stuff – the travelling is knackering. So, if I’m going to do this thing and get out of bed, I’ve got to really believe in it, because it hurts. Bring tired and being old, it hurts! But I bloody love it. So, yeah!

Part of the challenges, especially as you get older, is finding musicians who want to go on that journey with you. Because there are a lot of musicians out there who really do want the fame and there are a lot of other people who think they want the fame, but aren’t prepared to put the work in. Finding that holy grail – the people who will go on a genuinely artistic journey, it gets harder year on year.

Yeah. Our bass player is the bass player in Pulp. And our drummer is the drummer in lots and lots of different, very credible acts. Our guitarist plays the guitar on a show in the West End, about Meat Loaf – some Bat Out of Hell sort of thing. And they all do these different things and get on with it… but they also blow things out to make sure that they can do this because they really love it. I’m thinking “well, why the bloody hell do you want to do this? You’ve already got things mapped out that are much bigger and better than this!” But they are passionate and, in session music land, I’m sorry but that’s rare.

Usually, you can say a band is a band. These four guys are here because… The Ramones, that’s a band! They love it and that’s it. Well, this is not that. This is me asking these guys that I think are amazing to come and do this small thing and they fucking love it. So, in a way, it’s better than a band, because they can wander off and do other things. They’re not locked into all the fucked-up stuff that goes on when four blokes try to spend their lives in each other’s pockets, you know. There’s a kind of liberation, but there’s a musicality to it. Like you said about the Undertones. If you love music, you love music, that’s what saves it.

That collaborative spirit is something that can easily become lost with bands that have been around for a while. You fall into those ruts, and increasingly in the era of the internet, for a band to break out of their established position is really hard and the mauling that you get through social media is enough to push people back into their boxes awfully quickly.

Yeah, I know – I’ve already taken a few kickings over this [laughs].

But yeah, it is worse doing the sort of living dead thing – this is what we do to the death, you know. That’s really bad. It has to be real, and it has to be alive and, if it’s not, then fucking bin it.

I tell you what, working with Billy, that’s a thing. He’s older than me and he’s got an attitude… because he’s an artist, he knows when something’s alive and visceral. He gets so bloody animated and excited about that. And I’ve made many, many albums in my life in studios, with engineers with all the rest of it, producers and other musicians. Seeing someone so excited and animated, that’s a musical act and, in doing that, you become excited. So, yeah, I suppose you have to search for the thing that matters for it to be real, and then other people will get it.

Otherwise… People see James Taylor doing this sort of Hammond Organ, funky jazz, sound and then the record company calls up [carries on imaginary conversation]:

“Alright James, can you make a funky jazz record?”

“Oh yeah, I can I suppose.”

“Good, because that’s what you’re known for!”

“Yeah, I suppose that’s what I’ll do.” [Laughs]

So, you want something that’s igniting you. Then you don’t feel sixty anymore. It’s that sort of thing.

There’s a good litmus test, when you’re demoing material – basically, if you play it back and it makes you stand up and pace around while you’re listening to it then it’s in the right place. If you just sit there, completely unmoved, then that’s the point to drop into the folder marked “nice idea, poor execution”!

Yeah, and there’s a lot of stuff in that folder, and that’s fine. In fact, sometimes the stuff in that folder resurfaces in different ways, and you realise how you can bring it to life.

So, yeah, there’s a lot of scratching your head, not thinking about music. Not touching music. I’ve got an allotment, I keep bees – doing things that have nothing to do with music, but the whole time there’s something sifting, and then you get a feeling that something’s coming – something forming on the horizon and then it lands and it’s like “now, we’ve given birth, here”. And it’s usually a brief period and then, afterwards, you realise that was the creative act. You know when you’re laying it down, when I’m demoing it and it’s coming together, I get really emotional. Like “Christ, this is really shaking me up!” And then you play it to others, and you see it working on them as well, so you know. You know, and it’s rare. It’s rare that you stumble on those things. But it’s so bloody good when you do.

This album sounds like it was tracked live – how long did it take and where did you go to do it?

The backing tracks went down in one day, the vocals on the second day, and we mixed on the third day [Amen – Ed.]

All of this was at Ranscombe Studios in Chatham, which is the studio I worked in with Billy Childish. The engineer, Jim, has really got a lovely kind of… he’s very musical, he’s got a lovely way with recording. I didn’t think I’d be able to do the vocals, because I’ve never really done that before, but I managed to find a key that sort of worked for me and Jim set up the microphone with a big compressor on it – a lot of compression, so the weak bits of my voice were pulled up in my cans, and that gave me confidence. There was something about his chemistry and his ability to lead me through that. That day was difficult. So, we got a vocal out of me, and mostly…

Anyway, it was a three-day thing, and a lot of laughs. It was lovely, so lovely. It was so full of musicians being able to do something that they love in a completely unrestricted, unmonitored way. There was nothing to do with industry or trying to get somewhere. It was purely for joy. Yeah, it was special, we have to do it again.

It’s interesting, you mentioning the compressor on the vocal, because it’s vulnerable at the best of times doing vocals, and the heavier and louder the backing track, the more you really need that kind of boost in your ears. Otherwise, you can really feel like you’re getting glost amidst the chaos of it all, and that’s quite hard to overcome, I think.

See, I’m totally inexperienced. I record other vocalists and [laugh] my take on singers over the years has been “Christ, they’re difficult, aren’t they?!” I mean, musicians look at each other and go, “yeah, singers, eh?!” [laughs]. Well, now I’m a singer.

But yeah, I did not know what to expect and Jim really did hold my hands through all of that and I think the key really was the compression, because if you’re not a singer, your voice has got a few notes where it’s strong, and lots of other notes where it’s not. And the compressor lifts those up and supports you. I didn’t expect that, but it gives you an instantaneous shot of confidence, so something happened to make that work.

Yeah, singing is all about psychology, isn’t it? Singers are anxious and twitchy, and they want to get it right. It is a difficult job, I think. And so, the voice is the instrument that is the most vulnerable. To find a way where you’re comfortable and relaxed… it will be interesting to see what happens next week at Ronnie Scott’s because that could be where all this goes wrong. [Laughs]

I was talking to a friend of mine about exactly this – when you’re a singer, you’re dependent on things that you can’t really control. Obviously, you can do all the advisable things, like the right diet, and avoiding dairy before a performance, and good warmups; but you can still have that moment whether because of nerves or ill health that you choke and nothing comes out, and that can be so debilitating. But yeah, when you said that singers are anxious, I think that’s exactly right, and it’s usually right before you go on stage. Once there, you hit a note and suddenly realise that you’ve got it.

Yeah, and I did used to be in a choir because I wanted to learn how to do string arrangements and stuff like that. And that Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass thing showed me how you could do orchestral arrangements with violins and cellos and things. But what I got from singing in the choir was what you just said – that frame of mind. I was a bass and a baritone at times. And, if I was relaxed in that role and knew where it went and knew my voice was producing the resonance and tone that I wanted, then it was an utter joy. All other times, it was a total swine and the more stressed you got about it, the less tone you could produce. It’s funny isn’t it, it can really trip you up.

How far do you demo, because things like Chicken Leg sound really spontaneous.

Chicken Leg, err, yeah, I had the band here in my studio and we were working on the vocal numbers, and I felt we probably would need some Hammond instrumentals as well. So, I simply asked the guitarist to take one element, the bassist another, and then the drums another. Those things, you just shout out. Honestly, you don’t write them. You just shout out to go up a fourth here, or whatever.

Chicken Leg, there’s nothing to it, is there? The other instrumentals are a bit more structured. Maybe that slow instrumental is a bit more structured, but yeah – they’re the sort of things that I write while they’re loading their gear in. They’re an afterthought, because if you get too contrived and structured on things like that, then they won’t fly at all. It needs to have a joyful, throwaway feel to them. Instrumentals are like that.

My first shot at writing instrumental music really, you know, were theme tunes and things like that. And what I found is, for something like Chicken Leg, less is more if you know what I mean. Not too much structure. Just let the band be who they are, that’s it. And you capture that with a microphone, bang. So, no, there weren’t even demos. And the songs were demoed, just very quickly.

So, once you got everything down, did you already have a sequence in mind, or did you have to go through that painstaking process to get the flow and structure of the record.

Because we recorded it… if you think songs like Chicken Leg are Jimmy McGriff, 60s sort of things – or even early 60s type things. And then, things like My My My are sort of Stones-y, or The Who – She Dreams in Crimson is basically late 60s The Who Sell Out (which I absolutely fucking love). They don’t sit next to each other, but chronologically they follow each other. So, you go from a 1963 Hammond instrumental to a 1967 psychedelic, British R&B tune. Then a 1979 Buzzcocks type thing. So, we recorded it in chronological order – 1963, 1967, 1969, 1975… that’s how we put it down. And that made perfect sense.

But… Listening back, you ended up with 3 instrumentals, then some Who type stuff, then some punk stuff. And I realised we couldn’t present it like that, so then I started thinking how in the hell we could present it. And it was painstaking. It was very difficult. We kept changing it. I’m happy with the order now, more or less, and yeah – that is so hard. Because, I don’t think it would have been right to present it as a chronological journey – it didn’t feel right, even though it flowed very easily in the studio.

That’s really interesting that you thought of it that way. I love the art of sequencing albums, and I think that yeah, it would have been very strange getting progressively heavier across the album. Because, as it is, it kicks off with that very punky title track. The second side, I guess, is a bit more psychedelic – The 4th Dimension and Small Thing are both on there, so it feels more… expansive, in a way. The first side is a touch more concise – but then you’ve got My Wife at the end, which is a lovely ending, and much more effective I think than if you’d gone for something a bit heavier.

Yeah, yeah. Well thank you. I think it is hard to sequence things in that way. So, you just experiment and try. And likewise, it’s hard to sequence those tunes on stage. I suppose, when we do Ronnie’s next week, we’ll have to put in some of our normal repertoire and then sequence this in. So, yeah, you get a feel for it. Now, on stage, the whole thing for me has always been that we don’t do set lists. We start playing and then see what’s happening with the audience. Is it working? I they responding? Then the next song follows from that. So, from the first song, we know what we’re doing next, and that’s how the whole thing opens out. It’s like being a DJ or something.

Yeah, we don’t do set lists. And when people writer set lists in the other bands I’m in, they’ll spend weeks over a set list, and they’ll be asking “how about this” and “how about that?” And I’ll ask them, “well, how will you know?”

There’s no way of knowing and what happens, then, if it’s wrong? You have that set list and, after the third song the audience are looking at their feet, do you plough on with the next song, or are you going to give them something that’s going to reel them in?

So, that relationship between you and the audience is… every audience is different. You have no fucking idea what they’re going to do. So, that relationship has to be very, very real, and you have to be aware (and I am aware) of the audience. And I think that’s going to be challenging, because I guess I’ll pick up the people who are uncomfortable with punk rock and all the rest of it. And I’ll think “you’ve bought a ticket; I don’t want to piss you off!” [Laughs]

We’ll have to find a way to make it work. I’m usually pretty good at that.

It is hard, but you’re right that the relationship between band and audience is important, but I guess it also is impacted by the type of music you’re making. For example, if you’re doing more progressive music, where one track flows to another, it may become necessary to plan things a little more.

I’ve had my period of touring with sequencers and all of that sort of thing, and you click on the start, and you’re chained to this fucking thing, and that’s… no. No, we don’t do that now, thank God. We really are… we don’t know what we’re going to do when we walk on stage. And the band, as we’re walking on, they ask me about specific songs and then, ten seconds later, you’re in front of the audience looking at them, and you suddenly know what you should do. That relationship is what makes it so good – that real, genuine interaction between you and the people can never, ever be repeated. It’s completely unique every night.

I suppose the big question for you is if you want to go on stage with something hard edged and really shake the audience up or ease them into it.

Oh, I’ve already answered that. I have to go easy. I have to really build up. It wouldn’t work. In other venues, yes. But at Ronnie’s, no. And we are doing some punky venues, so we will get a chance to do that. But first of all, we have to occupy the spacer that people know us for. Then we have to move toward something different.

Obviously, your band is so experienced and have worked with all these different people – do you find their sort of musical sensibility bleeds in?

Andrew says, “when I play Pulp, it’s all quavers, and with you, it’s all semi-quavers”. So, he likes to come and play with me because he can move. He’s really into that James Jameson, Motown sort of bass thing. But I think him going and playing for Pulp influenced me, because I was thinking, “Yeah, rock ‘n’ roll, that’s bloody great, I’d forgotten all about that! And I now know that you do that!” It would never have crossed my mind that he’d be open to it otherwise.

The big thing here is presenting it to my musicians and them taking it seriously. It was quite a thing really, because it could have backfired. The fact that they were excited about it as well was a huge surprise for me and so bloody good. But yeah, why not.

As you say, people love different forms of music. But yeah, because he does that, he can do this, no question.

And, certainly Mark on guitar can, because he does a whole range of rock ‘n’ roll type things. So, really it was a question of, we had a Vox AC30, do we go up to ten? How hard do we drive it? Keith Richards? It was finding that balance where the guitar sounded Stones-y, rather than anything heavier than that. And then, for the punky stuff, a bit more distortion.

And Pat, he’s just into everything. He’s one of those prodigy drummers. On Instagram, he’s got 30,000 followers or something. He’s a drummer’s drummer. He does everything really, and he was just over the moon – Moon, he absolutely worships Keith Moon, so he wanted to do all of that. They’re musical people, and yeah, what they do in other things, they can bring it to the party, of course.

There is something, isn’t there, about turning up the amps and letting the wall of noise rush over you.

No, that’s right. But also, the eclecticism and being able to jump into a ballad, or a more musical instrumental, or being able to move things around. I think I probably suffer from ADHD, because I’m very quickly tried of just going down one road. I need to have a different tempo and different approaches, and I come at the thing from all sorts of different angles. And that’s what I tried to do with this record – entertain myself, really.

I was wondering, because a couple of songs in particular I found really evocative. 4th Dimension was one, where I had this really powerful image of a leather-lined, snoke-wreathed, speak easy, and I was wondering how much you had an image in your head while creating these tunes – particularly the more off-the-cuff instrumental pieces.

Yeah, because I’m a Hammond player and the black Hammond players in the US in the late 60s, early 70s were playing exactly what you just described – those venues. Jimmy Smith owned one – he owned a jazz club in Los Angeles which was exactly how you described it. And, of course, films like The French Connection, you see those clubs in those amazing American films, and the Hammond players were doing it. So, you know that’s exactly what you’re going for.

That particular song, it has a melancholy vibe, The mood is melancholy and introspective, and then it opens up into something soulful and gospel. So, it crosses the line into something more spiritual even. The whole gospel thing influences the organ so much. It’s a church instrument in the Aretha Franklin sense of the word. So, you can do a lot with the Hammond, if you are stepped in that gospel tradition. So, that thing about being down and melancholy, and slow, with nothing much going on; and then it rips into something, and the bass player has his semi-quavers [laughs], and it starts to move. That transition is exciting and then, because the band is doing that – improvising – I can feel that they’re alive and excited, so the improvisation becomes more exciting because their energy feeds my energy, and we let the excitement build in that way.

Yeah, the other interesting thing for me, from what you’ve just said is, there’s so much about using imagery. Seeing things and turning that into music in general – in all forms of composition. If you can get an image in your head – something beautiful or amazing that stays with you as you’re composing, that’s a bloody useful trick. And other people will pick up on that.

For instance, I’m writing music quite a lot for adverts, and I wrote a piece of music and, while I was writing it, I was building a train set – a 00-gauge train set… just fannying about really. I was enjoying it; it was such good fun. I spent hours and hours, like “that can go there, that’s working, yeah.” And then coming upstairs and writing in my studio, all really playful, like a child, you know. And then going back and playing with the train set, it was great. Anyway, we put it out and the first thing we got was for the BBC – a programme about a guy building a train set. Yeah, that’s what that was used for.

And the guy who owns my publishing company, he was like “this is how it works, man!” Debussy and Ravell – it was all about image. You see a river and the ripples, and you try to make that into music. You turn your piano into that river. So, that stuff is evocative, if you can do that. And I think people can. And that’s been quite a trick, increasingly as I get older.

I love the fact that this album is out on vinyl – it just suits the sound. Was that important to you to have it on this format?

Oh yeah. God yeah! Totally. You know, it’s such a lovely commodity. And the thing I’m excited about is I have a copy. And I’ve got it on white vinyl, and you know, playing a record… as I say, I’m sixty and when I was ten years old, I was putting records on. I find the whole… Spotify, I’m sorry but it’s not… I mean, great, you’ve got 50,000 tracks or whatever. Good, that’s good. I’ve just got this record here, mate.

Totally, I love vinyl, and always have done. I’ve only done one album without, and that’s only because the record label wanted to “experiment”. And everyone complained, including me. [Laughs]

I can’t use Spotify. For me, it’s either CD or vinyl. Even reviewing, I’ll work from a download, but if it’s something I love, I usually end up buying it if I can afford it, because it just doesn’t seem real, somehow, otherwise.

I’m glad you said that, because I feel that way and it’s one of those things where I feel like I’m the one being manipulated here. I don’t want to play games with those big digital companies. I want my own autonomy. This is mine. It’s my record, you know. So, yeah, I’m excited to be an owner of records. Records do excite me. And I’m excited when I see other people. It’s a funny kind of collector-y type of thing I suppose. But that idea that you can turn on a tap and out comes the music [scoffs] yeah, boring, isn’t it? [Laughs] Yeah, I love records.

I was vehemently opposed to the shuffle button on the CD player, but yeah, so many people seem to listen to Spotify on a permanent churn, and it reduces music to the level of elevator muzak – I resent it.

It’s not empowering, is it. You’re so passive at that point. You’re a passive receiver. There’s no autonomy, there’s no independence – independence of thought. This computer is telling me what to listen to next, and what to like! [Laughs] Leave me alone!

So, do you think you’ll tour this set slightly differently? Is the punk edge going to drive you to different places?

Yeah! We’ll try and make it work at Ronnie’s. If it works at Ronnie’s, it’ll work anywhere. We’ll take it out, and we’ve got a few gigs around the UK. Next year, we have the Barbican, which we’ll do with an orchestra. So, that’ll be the orchestral, soundtrack-y stuff that we write. Then, the orchestra stops, and we’ll play this. So, we’ll sandwich it in there. So, yeah, you know what else? It opens up a whole lot of new possibilities. For instance, I am really into classical piano music, and I play bits of Bach and Beethoven, and all the rest of it. I’m going to do a tour in Italy of just me and a piano. So, I’ll be playing a bit of Bach and a bit of Beethoven, and then I’ll do a song off this album – My Wife or something – just me and the piano. And then do a bit more – Debussy or something – just playing the piano and singing. Because you don’t get that. Talking about fusing different musical worlds, if you go and see some Beethoven up at the Wigmore Hall, you’ll get Beethoven, and it’ll be incredible. You know. You won’t find as higher quality anywhere in the world. But the geezer’s not going to sing you one of his songs! That doesn’t happen. [Laughs] So, that interests me because it’s something new.

That’s important, isn’t it, because the composers were pushing the limits of what they could do. And the piano – look at Jerry Lee Lewis, or Ben Folds, and you realise just how versatile it is – it’s a rock ‘n’ roll instrument when you want it to be.

Yeah! Or Little Richard. Bloody hell! I know. Of the big five rock ‘n’ rollers, Little Richard was the best. It’s just insane! It’s like seeing a madman let loose on stage – I mean, you’ve got to want that. As an audience member, for something that mental to happen in front of you – it’s berserk. It’s beyond entertainment, it’s a spiritual thing. As a point of fact, he was doing church in a rock ‘n’ roll way. What goes on in those churches when they start to lose it, that’s what he was doing on stage, and it’s amazing. And that’s what I try to do with my gigs, is to build it to a level with the audience where it’s fever pitch. I’m wondering if this will have, and I think it probably will, this new thing we’re dabbling with – will enhance that. Yeah, Jerry Lee Lewis – how does he do that? I’m a keyboard player and I can’t do that! I certainly can’t go [impersonates Jerry’s hands racing over the keys]. He moves his hands, doesn’t he. And he’s got his microphone stand stuck in front of him. But yeah, I bloody love him. There’s not enough of that sort of stuff, is there, really? [Laughs]

It’s all dynamic isn’t it. It’s interesting – you mentioned Ravell, and I was talking to someone else about Bolero being the ultimate in dynamic…

The crescendo, yeah

There’s such space for this and it’s something that’s lost in more formalised music – you stick in your lane and it’s heavy or its light, but it rarely builds in that way. That’s what bands like Spiritualized and Mogwai are really, really good at doing.

Our trumpet player played for Spiritualized – he toured America with them. I never got to see them. But yeah, dynamic is everything. If you can drop down to nothing and reach up to everything and take the audience with you, you’ve got a really serious tool kit there. Yeah, again the Hammond organ is very good for that. You can make it a whole orchestra, just blasting the roof off the place, and then just drop right down to nothing, and let the audience come down with you, leaving them wondering where all the space came from. Yeah, the use of dynamic. I can’t stand it when a band stands on stage and it’s like ‘this is how this one goes” and for 16 bars you’ve got this bit, and then you’ve got 16 bars of another bit. Then it goes back to the bit before for another 16 bars. Nirvana were fucking amazing, because everything was about dropping down to nothing and then exploding. So, there’s a massive musicality there and if you’re missing that dynamics trick, there’s something badly wrong normally, I think. And also messing with tempos. Speeding up. That’s a huge trick. The Who were kings of that. Do you remember that thing they did, Rock ‘N’ Roll Circus with the Rolling Stones – Ivor the Engine Driver “you are forgiven” and all that – the final minute of that. You talk about music making you jump up and pace around and all that, that does! Yeah, driving tempo up, as a trick, is a really nice thing. Yeah, you’ve got to have all the tricks, use them, and know where to use them.

See James out on tour:

12th Rochester Cathedral

17th Benenden Hall Benendenm, Kent

December

20th 229 London

21st The Boileroom Guildford