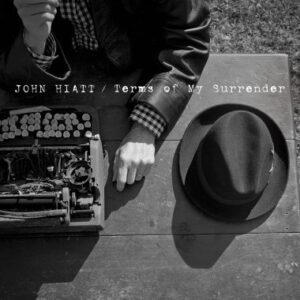

Twenty-six albums and no sign of losing his muse, John Hiatt is back with ‘terms of my surrender’, a stunning, slow-burning piece of work that works its way under your skin and stays there over its eleven tracks. A singer-songwriter in the mode of Dylan, Cohen and Neil Young, John Hiatt has a distinctively gnarled voice and an ability to build the most beautiful of crescendos within his world-weary music that makes the hairs on the back of the neck stand up (see ‘all about my place’ for evidence of this) and ‘terms of my surrender’ is a fine addition to his lengthy back catalogue.

Opening in singer-songwriter vein, ‘long time comin’’ gives the impression of an aged bluesman sitting on his porch and ruminating on the past, only for the band to come in half way through and build the piece towards a beautifully ragged solo that is awash with distortion and emotion. It is a song that is memorable in a number of different ways, whether it is the quiet, opening strum that sticks in your mind, John sitting alone, eyes closed, playing the song; or the beautiful build that sees the band lend depth and power to the composition, ‘Long time comin’’ is the perfect opening track. ‘Face of god’, in contrast, is a delta blues shuffle complete with harmonica, subtle percussion (Kenneth Blevins) and a touch of the banjo (Doug Lancio) thrown in for good measure. It’s a great tune with plenty of energy and style that keeps the foot tapping, whilst ‘Marlene’ is a gentle love song that wouldn’t sound out of place on Clapton’s recent ‘old sock’ set, the countrified guitars and rough-hewn Americana vibe making it a song to be sung around campfires for generations to come. An album highlight is the dead man’s blues of ‘wind don’t have to hurry’ the opening of which howls across the bleached bones of the fallen, ‘na na na’ chorus notwithstanding, thanks to its dry-as-tinder guitar work and John’s distinctive vocals. When the band does come in, it only emphasises the lazy rhythm of the track, Nathan Gahri’s bass throbbing away at its heart and powering the chorus to the track’s end. A hazy track, ‘nobody knew his name’ recalls Dylan’s more story-telling orientated song-writing from ‘Tempest’ with its repetitive central tune, atmospheric flourishes from the band and, at the song’s heart, John’s tar-stained and gravelly voice intoning the lyrics. As if wary of letting the record slip too far into introspection, however, John and his band pick up the pace with the taut groove of ‘baby’s gonna kick’ which, with its handclap rhythm, harmonica breaks and honky tonk piano, is more or less guaranteed to get feet moving on the dance floor. It draws the first half of the record nicely to a close and it keeps the mood varied and interesting – in fact you can imagine the song really getting the blood pumping in a live setting.

The album’s second half kicks off with ‘nothin’ I love’, a tough blues song that lists the narrator’s faults (cigars, Poker, drinking and pills), pointing out that only the object of the song is in any way a healthy passion to pursue. As with the opening track, John takes the lead, the band only appearing after the second verse has been dispensed with, a trick which allows a certain emphasis on the lyrics and the music to build around them, some gloriously dissolute solos appearing towards the end. The title track is a late night blues, played by the band as the barman sweeps the empty space in front of the stage and the smell of old cigarette smoke and spilt beer gently wafts through the building. Quiet and restrained it’s a love song that ends with the beautiful sentiment “I love you too much, baby, to ever say goodbye.” ‘Here to stay’ features some great slide guitar and builds from its notionally quiet beginnings into a powerful and detailed piece by its conclusion. ‘Old people’ looks at old age with a wry smile and shows that John has lost none of his twisted sense of humour, some simple slide work gently weaving around the chorus of “old people are pushy because life ain’t cushy!” As the song draws to its close with its massed vocals, only ‘come back home’ is left to round the album out. A quiet, contemplative piece of music it ends the record on a thoughtful note, the final words being a plaintive “I wish you’d come back home.” It’s touching, heartfelt, and it leaves the listener with a gentle melancholy best resolved with a glass of whiskey and another spin of the disc.

John Hiatt, like Dylan, is an arch story teller. It is not always clear where the narrator takes over and John ends, and the music clearly comes from a deep well of inspiration drawn from life’s rich tapestry. ‘Terms of my surrender’ sees John on fine form, his band well used to the subtle nuances of his music and producer Doug Lancio well versed in keeping the sound warm and analogue. It is a record that contains no instant pop songs to hold on to, rather it is a piece of music that slowly builds in the consciousness, the ebb and flow of sound within the tracks destined to pull the listener in and keep them there, and for fans of John Hiatt and/or the blues ‘terms of my surrender’ is a triumph, a beautiful, subtle, melancholy record that contains sufficient depth to warrant numerous repeat plays. If you have not yet explored Hiatt’s work, or if you simply want a record to accompany you on those late nights when the household is empty or asleep and all you have to hand is a glass of whiskey, ‘terms of my surrender’ will prove to be your ideal companion.