Although John Wesley has had a varied career, I first encountered him as the guitarist for Porcupine Tree. His presence, not only as a guitarist, but as a vocalist (check out his spine-tingling performance on ‘Way out of here’ from the ‘Anesthetize’ DVD) was a vital part of a band made up of virtuoso musicians and his subsequent work has only enhanced his reputation. With Porcupine Tree on indefinite hiatus since 2010, John Wesley has remained busy, appearing alongside Marillion, Sound of Contact and Big Elf as well as producing nine well-received solo albums.

This year, John released the stunning ‘a way you’ll never be’, an intelligent and eloquent look at the increasing sense of dislocation felt by people in an ever-changing world. The album is masterful, not only in terms of lyrical content, but also musically, and John draws liberally from a wide range of influences. The result is a timeless fusion of progressive and alternative rock that stands proudly alongside the very best of Porcupine Tree’s output whilst having its own distinct character. Initially, when I discovered that I was to have the opportunity to discuss the new album at length with John, I was keen to ask about tone and guitar work, but as I spent more time with the record I became more and more intrigued by the lyrics, especially when I read an interview in another publication in which John briefly talked about the strong influence of Hemmingway on the central theme. This interview, therefore, covers a wide range of ground and provides a fascinating insight into the creation of one of the finest albums of 2016.

I was reading an interview when you were talking about your lyrical influences and the theme of disconnection that runs through the album and you mentioned that a particularly strong influence was Ernest Hemmingway and his notion of “the lost generation” and I was wondering if you could expand upon the parallels between Hemmingway’s post-war lost generation and today’s society?

Yeah, it’s a really interesting thing because you can kind of break down, or at least from my point of view (and, of course, I’m not a sociologist), into firstly, the fact that we’re in a period that is not only a post-war (almost a state of war) situation. A lot of friends of mine are veterans that have been there and fought that war; as a matter of fact a very close friend of mine fought for years and now his son is going off to fight; so we have that generation of people who are coming home from conflict, dealing with the PTSD from all that and we’re trying to reintegrate our veterans into society. Then, secondly, there’s that other, millennial generation and I’m not sure that college-age kids right now would be considered millennials, but I’m going to lump them in with that category, and a lot of them are having a hard time making their way. You’re talking about thirty-year-olds still living with their parents who haven’t, then, really found their way or, if they have found their way economically, they haven’t been able to break the chains of home. And then you get guys who are around my era, I’m in my fifties, I’m fifty-four, and the landscape ahead of me has changed in ways that I could never have imagined. When Porcupine Tree ended, I did my last tour with Steve Wilson and played with the Steve Wilson band in, maybe, 2011, and the landscape for music and my whole future has changed in ways that I can’t imagine, so if you take all three of these generations and you look at the ex-pat thing that was happening with Hemmingway and their loss and bitterness and a lot of that was explained in “the sun also rises” and some of his stories through ‘the first 48’ and the Nick Adams stories and things like that, I started to see a parallel. I’ve garnered a lot of life lessons out of reading and writing in general, but being a Floridian and having spent a lot of time in Key West, a lot of life lessons out of Hemmingway’s writing. And I started to see a modernisation of that Lost Generation. Over here there’s a big thing happening with the Social Justice Warrior crowd. They’re becoming so sensitive that they’ve created safe spaces and ‘trigger warnings’, you know. I forget the exact story, but it all started when a student was offended in class because they were reading a famous Greek story, and you can Google this, but it started this whole thing where the student said they should have been told what the story was about and it triggered some Post Traumatic Stress situation and it’s got to the point where certain speakers are being banned form colleges and certain gender-pronouns are being banned from colleges. There are safe spaces. There were several incidences where they created safe spaces like Adult Colouring Books, toys like they were in a pram or something and you can go there and recover if someone is saying things in their speeches that you don’t want to hear or offends your sensibilities. And then there’s ‘micro-aggressions’, you know, using improper gender pronouns like if you call someone a ‘her’ or a ‘he’ and they don’t identify that way, there’s a huge micro aggression culture of how you have offended them. Or if you say to someone something like “we’re an ethnic melting pot in the United States” that’s a micro aggression. If you say to someone that it looks like they have a heritage from outside of the country, because America is a melting pot, especially college campuses, but if you say “hey! Where’re you from?” well that’s a micro aggression where they might say that because you’re suggesting they look Latino they’re not American when all you want is to know a bit about their cultural heritage. There’s a real… professors are losing their jobs, students are being expelled over this. So there’s a sensitivity in that part of life and if you look at it all, people are lost. So I kind of tied it in with Hemmingway’s Lost Generation thing. I went back to the book, ‘the first 48’ and started looking at the characters in those stories that I could relate to and there were things going on around me in life that I was reading and seeing that were reminding me of lessons I’d learned from his writing that I’d learned that he wrote in the thirties. So, I know that’s a long-winded explanation, but yes I definitely see a correlation and it’s not just with the younger generation. Because that’s another thing about Hemmingway’s Lost Generation. They were strictly to do with that generation that experienced WWI, either from home or shortly thereafter and in that age group, but mine is broader, even going to people like myself who are looking at their last days and wondering where to go from here.

I hadn’t appreciated the extent to which things had become so sensitive and difficult in America but we experience similar things here in England where you have to be increasingly careful about how you choose to express yourself. That sense of dislocation, I think, flows very much into the music where some tracks such as ‘by the light of the sun’ where there’s an explosion of emotion and in other areas you’ve got songs like ‘Silence in the coffee’ where there’s almost a resigned sense of apathy…

Absolutely, and again there’s the honesty and sometimes you have to face up to… Let’s stroke it with a broader pen for ‘silence in the coffee’. Has there ever been a morning when you woke up and faced that morning coffee and knew that your life was about to change forever and that there was nothing you can do about it? You’re just staring into that coffee and there is this deafening silence that envelops you. And I wanted to express one aspect of it and there are times in my life when that’s happened to me and I was reading a story by Hemmingway called ‘Mr and Mrs Smith’ and in that story the couple experienced things… there’s also a dialogue between the couple in ‘hills like white elephants’… that reminded me of some of those mornings when I woke up and faced that cup of coffee and faced that person and realised my life had changed forever, so I tried to distil that into an event, or a moment… capture a moment and that’s where that song comes from. It’s the capturing of a moment – could’ve been, should’ve done… you know? Lives are filled with could’ve beens and should’ve dones.

It’s a beautiful song and weirdly, when I went to review the album the download had corrupted and it was the first song I heard and it kinda worked at the start there! One of the things I’m always very interested in is the art of sequencing a record so that it becomes a journey and the album, I think, flows beautifully, but then when I looked at the vinyl release it has a different track listing?

Yeah, when I went to do the vinyl, the order that I had placed on the CD didn’t fit on the vinyl [laughs] it was like “oh my god!” and it was a real struggle and it took days for me to re-assemble the vinyl in a way so that, even though the flow was different, it didn’t lose the important elements of that flow to me. And we gave up the fourth side and some sides were shorter than others, but it was very important to me. I just couldn’t go “oh well, that song’s that long and this song’s this long…” and just chuck them all together, it was a real effort to sit there and make sure that I could work within the constraints of the physical time limitations of vinyl and yet not lose that flow.

It seems to me that, particularly in progressive rock, it can be harder in many ways to sit down and create that sequence than it is to initially write some of the songs…

It was difficult. I mean, it’s difficult if you want it to be perfect and sometimes we tend to ignore instincts and even though when I started assembling the songs and I started listening to them through as a set, the order kinda dictates itself, but sometimes we ignore our instincts and we get to smart for our own pants and try to fight what is naturally going on. Ultimately, lyrically and musically, the flow, it dictates itself.

And it’s hard to because right now I’m trying to put together a live set and I so want to end my live set with the epic ‘pointless endeavours’, but that ending doesn’t work live. At all. And I had to discover that first hand. [Laughs] It was like “Oh my god! Don’t do that again!” But it’s the way it should end. But it’s a live show and it does encompass other material, so I had to move things around to make it more dramatic for live because I’m playing in front of a crowd. But there’s a side of me that says that ‘pointless endeavours’ lyrically caps everything and sums it all up and sets the stage for the next set of songs. It has to be at the end. But it doesn’t work live so…

Different guitarists employ different styles, and when I listen to you I’m reminded of progressive artists like David Gilmour who play with great restraint and eloquence, except occasionally when you get a track like ‘unsafe space’ where you go into this jazzy Jeff Beck thing and I wanted to ask how you have explored your style over the years and what elements have inspired you?

Well, I think all of the usual suspects have definitely informed the playing. Alex Lifeson was a big influence, Jeff Beck was a huge influence, Clapton, Gilmour, I mean there was a time when I was teaching guitar, I would teach kids the minor pentatonic scale and then they couldn’t put a solo together. So I would make them transcribe and learn the ‘shine on you crazy diamond’ solo, because everything you need to know about playing a rock guitar solo, or at least in the minor pentatonic, it’s all there. So, as I developed as a player, like anyone else, I was a kid and I was young and people said “you need to be doing this!” and I said “OK! I’ll try and be Van Halen…” I’ll never forget playing ‘Eruption’ at a party after I’d spent hours and hours and hours playing, I played it horribly and I realised that “my god! I don’t do this!” And then I remember chasing techniques and things that never showed up in my playing. So, it took a long time for me to figure out what was important to me as a player and it’s a constantly evolving thing, you know, I’m fifty-four now and I’m not the guitar player that I was on the last Porcupine Tree tour, I’m way beyond that guitar player today than I was six years ago. That’s six years and a lot of hours of playing, you know, and I had a friend of mine… I was chasing this certain set of techniques and he said “do you ever listen to that kind of music?” and I said “errr, no…” and he said “do you own any of it?” and I said “no…” and he asked “then why are you trying to play it?” and I told him “it’s because I should?!?” And he told me to get better at what I am, to take in what I can but to not try to be something that I’m not. That opened huge doors for me.

And, to make this an even longer explanation, when I was a kid I used to write the lyrics and melodies for my band, but I wasn’t a vocalist. And I didn’t start singing until I had to to make a living and I had no choice, not until I was twenty-nine. It was twenty-eight, twenty-nine before I really sang more than a couple of songs in a band set. So for years, when the singer was done singing the song and it became a solo, it became an outlet for me and I remember sitting down with a Kate Bush record and trying to play some of her vocal lines on guitar, and I’ve done that with many, many singers since and there was actually a time when I got paid to transcribe vocal lines into instrumentals, so, after hundreds and hundreds of figuring out vocal lines on guitar, even to the point where I was paid to do it, that has informed my playing and so that’s a big reason for my stylistic approach. Those are the elements that came together in the crucible to inform the style I have now.

I think there’s a temptation, particularly, when you start out to not only absorb a number of techniques but also to try to fill the space with a lot of noise and notes, and one of the things I noticed there’s a lot of space so that what you play really matters, and maybe part of the art of getting better at guitar is to learn when not to play.

Absolutely. And again, like anyone I can look back at some of the videos from my early days playing and I just cringe. It’s like “Oh god, what was I thinking? Oh I wasn’t thinking, I was young!” And, so the art of that… For example the first solo on the record, I was playing around with it and it was actually a very difficult passage to make interesting. There’s so much going on with the band and there’s this art of not crushing what the band is doing, but creating something that rises above what the band is doing and gels within it and, as I was playing against it trying to figure it out, one of the first things I came up with was this really long, held note. I can’t tell you how often over the next few months, after I had laid that down, I went back and listened to it and thought “is no-one going to say anything about this? Is this OK to do? Can I do this? I held this note for so many measures and then I did it again… oooohhhh” You know? Oooooohhh I’m holding two notes, listen to the way it screams and the wah! There is this release that I wanted to have happen emotionally at that point in the song, and those notes did that, but the guitar player side of me was “dude! You’re about six-hundred-and-thirty notes short of what you need in those measures!” So, it was a real… it’s a constant struggle to sit back and just acknowledge that it’s right, that it can’t be any other way. You have to let that be what it is. It’s a highly developed [laughs] and fought for art.

One of the things I love about the album is… I grew up with a lot of progressive rock, but then when I was a teenager it was all alternative rock like Soundgarden and Tool…

Oh yeah!

….and, for me, your record encapsulates what I grew up with in terms of Pink Floyd but it also draws on those more aggressive influences from alternative rock and it’s not… I don’t want to say contemporary because that implies that it’ll run out of date, but there’s a timelessness to it in the way it draws on so many influences…

That’s what I hoped. That description you’ve just given, that’s what I hoped because I don’t want to be dated and I’m always looking forward. I draw on the past, I drew on a lot of those bands, I love soundgarden, I love tool, I love Pearl Jam – I love some of the guitar dual stuff those guys do in Pearl Jam, and yet Robin Trower is a massive influence and Gilmour and Hendrix. And all of these things, I just look forward, I stand on their shoulders and try to look forward and do something that isn’t trying to relive a past that’s already gone.

It’s nice when you hear an album that is progressive. Because Progressive is a term that gets bandied about a lot and you’ll hear that an album is “progressive” and you’ll listen to it and you’ll think “well, that’s kinda Genesis…” so it’s really exciting when you do get a record that is genuinely progressive.

That’s what I hoped and that was my goal with the record and, believe it or not, but I’d say that there’s a lot of comments that I get about the record, but that is the one consistent thing. A lot of people have said “you’re really not trying to be something you’re not.” I don’t sound anything like Radiohead, but I love the way Radiohead always look forward and that’s what I tried to do here. I know I can’t be as out there and wacky as Radiohead because I don’t hear those things, I don’t think those things, but I know I can look as forward as possible in a different direction, maybe in some places they wouldn’t look, and that’s kinda what I tried to do with this record.

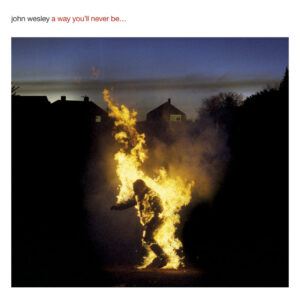

I’ve got one last question for you which is that with Progressive rock, one thing that is almost a given is having striking cover art and I wanted to ask how involved you are with presenting the visual side of your music?

It is very important to me and I’ll put it in context with the way I cooperate with the other musicians on the album and even the guy that mixed the album, for example. One of the things I’ve learned is that people who are really good at what they do have spent a long time developing their craft and there are a lot of people who can do a little bit of many things, but nothing as well as someone who actually just does one thing. So, the drummer, for example, on this album – we made ourselves take more time than we ever have before. But the one thing I did was, once I had shown him the parts and everything, I didn’t tell him what to do. I guided him and it was the same thing with the bass player, Sean Malone, I didn’t tell him what to do. I wanted Sean Malone on the record, I didn’t want John Wesley’s interpretation of Sean Malone. And the artist, Carl Glover, he did my very first cover. He’s done a lot of the Marillion stuff, the Porcupine Tree stuff, all of Steve Wilson’s and he works with Lasse as well – I wasn’t going to tell… I described the album to Carl and then I looked at the set of images that he sent me based on my description and that one was there. And then I said “arrange it how it needs to be – tie it all in with the music” and so, I believe in letting someone who’s really good at their art express their art and of course guide them and help them interpret your vision but, you know, unless you really want to develop that side of the vision then don’t. That’s one of the reasons I don’t use a keyboard player on the record I don’t play keyboards. I don’t hear form that perspective and, you know, once you’ve worked with Richard Barbieri and Damon Fox, you know, there’s nothing that I can do with a guitar synth and a keyboard that’s going to get anywhere near what those guys can do. And if I’m not in a room with them and I’m not writing with them, so I selected, again on my third album in a row to have all guitar. SO to go back to your question about art I let the artist – I gave him a guide, I told him what it was about and the passion involved with the characters and he came up with the flaming guy and it was like “Woah! That’s it! That. Is. It!” Every character on this album is on fire in some way or another. They’re either burning under the weight of their own doing or they’re burning to get out of the place they’re in. Burning with desire to become more than what they are and I thought that cover encapsulated everything I wanted to say with the record.