With thirty-two years of history under their collective belts, New Model Army are one of the most (if not the most) successful band’s ever to have avoided having a single chart hit. Followed by fiercely loyal fans and possessed of an enviable back catalogue that roams the gamut of sub-genres within rock music, the band have become a staple fixture of the festival scene, popping up at a metal festival one minute and a folk festival the next, always intriguing the audience and yet never compromising in order to fit into a particular slot. Intelligent and passionate the band have, over the years, sought to comment on any number of complex issues such as the financial crisis and the Falklands, and yet they remain contradictory and outside of any one political philosophy, their singer Justin Sullivan adamant that they are an emotional band and not a political act in any traditional sense.

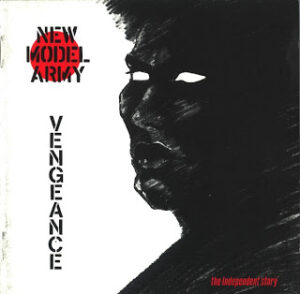

Given the band’s history and stature, it was with some nerves that we approached a phone interview with Justin (in order to celebrate the re-release of ‘Vengeance’), only to find him quietly courteous and contemplative, willing to answer questions in great detail and often with plenty of tangential elements as well. We present this mammoth session to you in full and wish only to note that this was one of the most interesting and exciting of the interviews SonicAbuse have had the pleasure to conduct.

32 years is a remarkable career for any band and NMA seem to have been more combustible than most, are you surprised at the longevity of the band?

Hmm – I think that would be an understatement! I think we expected to last two weeks and then we were always splitting up, always during the early years – I think I left the band six times! We were on the point of imploding at all times throughout our career… and still, every now and again.

Is that one of the things that has led to the quite changeable nature of the music that you’ve produced?

I think that if you get together people where at least… you can have someone in the band that’s moderately passive, but you need at least two or three very active or passionate members and once y9ou’ve got that, you’ve got combustibility… and you haven’t got that, it’s a waste of bloody time! If no one feels passionately enough to argue their point then there’s no passion. And people assume because I’m the one person who’s gone through the various stages of the band, people assume that the modern NMA is me – but actually it’s just combustible as it ever was because everybody who’s in the band now feels just as strongly about stuff as I do, so we still argue… which is the way it should be though.

Does that tie in with the political nature of your lyrics – surely they must lead to some arguments from time to time?

I think it’s much more about musical things that we clash, more than political things. I mean, one of the many… I think the driving principal in NMA we always refused to be a member of any club that would have us… you know, that old Groucho Marx thing and that’s one of those things, people have always said that we’re a very political band and, well… we are in the sense that these things interest me as a writer but we’re not in the sense that we exist to put across a political philosophy and this starts with ‘Vengeance’ in the sense that I remember in the very early eighties, it was a very political time. Punk, or most of punk, had become pretty left wing and if you lived in the north of England in the early eighties you couldn’t be apolitical really, it was a very politically intense time. So there were rumours about this new band from Bradford called New Model Army, really left wing, sort of socialist blah blah blah, and here we came, we arrived, and the first thing we released was this album called ‘Vengeance’ and the title track is the most politically incorrect, un-socialist in a way…. And immediately all the left wing, right-on, anti-Thatcher movements of the eighties… things like Red Wedge and even Greenpeace, decided that NMA weren’t welcome because we couldn’t be relied upon to say the right thing.

I remember that someone once said that NMA were “like a bull in an ideological china shop”, I think it was Paul Morely called it that which, I think, was about right really in the sense that we weren’t arguing for a political philosophy, and neither have we at any point. We have our political points of view, but music is not the place for philosophical argument, so I remember at the time there was the red skins and people like that, and then later on Chumbawumba and Crass and their music was designed to push a philosophy and the music was a backdrop and the lyrics were argued points, whereas our lyrics were just emotional – they were just emotional responses to everything with the certain knowledge that they were all contradictory. That was fine with us to be contradictory…. We could contradict ourselves, and that’s right because emotions are contradictory and some days you believe in vengeance, and some days you believe in forgiveness. It depends on what you’re feeling at the time and music is about emotional responses to things, not philosophy. That’s a long answer to a question isn’t it!?!

Is that, then, the difference between a reactionary ideology and, say, the tradition of protest songs that comes down the line of neil Young, Bob Dylan et al. that idea of protesting against a perceived injustice without nailing your colours to a given political mast?

Yeah – Kinda. It’s just interesting to write about what’s happening in the world but you’re not trying to adhere to a coherent philosophy. You’re responding to how the world is, which is what all artists do, isn’t it? And then people read into it a philosophy. I mean, I have a philosophy, but my emotional responses to the world don’t always accord to what I believe in, and that’s a common human experience I think. I’m sure you believe in certain principles, but I bet every now and then, in your life, you go completely against those principles because of how you feel. And music, in the end, is about how you feel. It’s spirit isn’t it.

So, perhaps, the difference between art and philosophy?

Yes – absolutely.

But, there is still that strong thread. I suppose it comes back to that idea of protest – but it seems almost fateful that ‘vengeance’ should be re-released at this time, given it’s very strong critique of the Falklands conflict and the fact that it is all coming back again…

Yeah – interestingly we actually played that song again recently,. For the first time in twenty-five years, and it felt, not only lyrically right on it, but musically it felt really good as well, it felt really right on it as well, and it was great playing it again. But, again, I’ll always take the opposite point of anything anyone ever says to me, that’s part of the nature of NMA, and people say “ah yes, it’s a deeply political album’ but ‘running in the rain’ is just a love song, a relationship song; ‘sex’ is a… I don’t know what that is [laughs], you know… and ‘liberal education’ is absolutely not left wing, you know what I mean, that’s a… in a sense it’s deeply reactionary…

For me, I suppose, that’s the difference, once again, between the idea of protest songs and music with an ideology. If you look at Rage against the machine they were pushing a dogma, while other bands with, perhaps political points from time to time, don’t have that thread that runs through their whole work…

Yeah – I think the point is… the point about that is that the whole point of the band’s existence is to push an idea, but that was never true of NMA. The point of our existence is that we really liked doing it [laughs] and it felt great. Politics is a part of life, but it’s not the only bit. It’s interesting because the album we’re doing at the moment, there’s one song that follows in the footsteps of ‘liberal education’, but an awful lot of the album is deeply not political, which Is just the way it happens to have fallen, because everything that’s happening at the moment, having released ‘today is a good day’ a few years ago, there wasn’t much we wanted to say that hadn’t already been said on that album, in a political sense.

One of the things about ‘today is a good day’ that I found is that it seemed to be really ferocious in times – an almost visceral reaction to the crises of the time – is that a fair assessment or is it over-reading the content?

It was written very fast in the wake of the collapse of the Lehman brothers, and the thing is though, that I, naively thought ‘hmmm’ – this has finally broken the spell that was first cast around the time when we first started in the early eighties, which was the year that the neo-liberal thing – the ‘let the city of London do their thing, they obviously know what they’re doing, let them create wealth for us all’ – and a lot of people, even thirty years ago, could see that there was some accounting fraud going on; they could see there was something that wasn’t quite right, and finally, thirty years down the road it is revealed that it wasn’t quite what it seemed…. But, we’re so deeply down that road that no-one quite knows how to go back. I’ve got a friend who grew up in East Germany and he said that the last three or four years has reminded him strongly of East Germany and when I asked him what he meant he said, well, everyone knows the system doesn’t work but no-one knows how to fix it. And so, the last three or four years, since ‘today is a good day’, everyone politically… people have… everyone is pretending that it’s going to be OK and that the system can be tampered with and fixed a little bit and meanwhile there are a number of popular movements, but as yet, the middle’s being squeezed but it hasn’t been squeezed so much that people’s outlook on life has altered to the degree that they’re prepared to… where they’ve got nothing left to lose. People at the bottom have… but they just want to smash things up and steal stuff like last summer – that’s a fairly normal reaction….

I could go on into this forever – but I feel I’ve led you down a political alleyway…

[laughs] the thing about ‘vengeance’ is that it is an interesting album because it doesn’t adhere to anyone’s particular philosophy. It’s just a ferocious response… rather like ‘today is a good day’ I suppose.

‘Today is a good day’ particularly…. It seems to be musically very heavy as well as lyrically….

Well, wait till you hear what we’re doing now [laughs] we’re doing something completely different right now and it’s just about finished. We’re quite excited – the thing about ‘today is a good day’ is that it’s very much a band-in-a-room album, whereas the one we’re doing at the moment isn’t. I don’t even know if it’s rock, really, I don’t know what the fuck it is. I don’t know how to describe it to people, other than it’s not a band-in-a-room! It’s rather less of a guitar album and more of a drum album.

It’s had along gestation though hasn’t it, I mean it was this time last year that your studio burnt down…

Yeah that’s right. The things that have happened since we did ‘Today is a good day’… just before that album, our manager of a long time died. And then we’d been unmanaged for a long time, so we found ourselves doing some of the management and it took up an inordinate amount of time but we’ve actually finally got something set up now. Then we had the anniversary thing, which was quite a distraction, I thought we’d do it right and I think, the 30th anniversary we did the right things, but it was a 9 month project really. Then we had the fire, lost a bass player and yeah… a long time.

One of the things I gathered from previous interviews is that you don’t write on the road, you actually find writing to be quite an involved process so this sort of lengthy period is probably a good thing?

The way we tend to write, certainly the last ten to fifteen years, probably longer, is that we have two cupboards. One is marked ‘musical ideas’ into which we put chord sequences, drum rhythms, bass lines and bits of jams and different ideas from all the different musicians in the band. Then the other one I put notebooks in which I write down stories that people tell me, or things I see or whatever and the important thing is to wait until both those cupboards are really full, and then you pull everything out and you start to put things together and eventually you put together an album which uses maybe 20% of your ideas store, and that… the important thing is to wait and the one mistake we made, which was kind of the ‘strange brotherhood’ era in the nineties, was we, myself and Robert, we were towards the end of our relationship really, and we started making an album and getting in the studio before we had cupboards full of ideas and we thought we’d come up with ideas in the studio – I think every band makes that mistake – and then you start arguing what a snare drum should sound like whilst everybody stands around for three years wondering what the hell you’re doing, and by the end of that, of course, we were broke [laughs]. But yeah, this time round, the ideas store was very full. Particularly, I think, beat-wise, one of the things about the way we write is that we tend to start with rhythm, maybe that’s different from other bands, everyone assumes we start from a guitar or piano like proper songwriters, but we start with rhythm (and then everyone goes “oh – now I know why you sound weird!” [laughs] And then this album is a rhythm album. Anyway it’ll all be revealed eventually! We wanted to have the freedom to produce it ourselves because we wanted to have the freedom to go around the houses and go up all sorts of blind alleys and explore ideas and not have a producer sitting there and telling us that it wouldn’t work – we needed to find that out for ourselves. The idea was always, then, to get someone really good to come in at the end and mix it properly and we’re almost at that stage and with any luck we’ll be mixing with Joe Barresi shortly, although that’s all slightly up in the air… but hopefully it’s him. He’s the guy that did Tool, QOTSA and soundgarden and all that heavy music.

I was wondering about if that’s one of the key things that’s changed over your career – the potential to record music , obviously, is so much more advanced than when you started – has that liberated the recording process for you to some extent?

A little bit but we still do actually do the same thing. We still start with demos which are done quick – you know, we throw up a couple of microphones and get the track done. So we do still demo. On this album we demoed and then we went somewhere posh to record a lot of tracks for drums, and then we came back here and finished it off ourselves in our own place. In fact, in some cases we recorded the drum tracks before we finished writing the songs! Which is an interesting exercise.

Which is strange because a lot of your music sounds so aggressive and spontaneous…

Yeah – I think in that era and at that point a lot of ‘vengeance’ was written before Robert joined the band. In fact it was written by me and Stuart and the main writing done during that era was Stuart and then after that it was Robert and then, after Robert left the band, it became Michael – so after Stuart it was drummers but actually, ‘Vengeance’ era Stuart was my main partner in it.

The other element of technology that is the elephant in the room is file sharing – especially the last album which seemed to become available over night – do you find it frustrating as an artist that your work can be shared so freely?

I don’t lose sleep over it, it’s a fact of life. It makes us careful about what we go out and play live. In the past we’d often play the majority of the album live before we’d recorded it and that’s actually quite good. With ‘today is a good day’ there were actually three songs that we went out and played live before we’d recorded them and that was good for those songs, but the problem is you write a new song and play it on tour at the back of Austria or somewhere and then the next morning everyone in California is discussing whether they like it or not, which is slightly weird. It’s instant. In the old days people made bootleg cassettes and they slowly made their way round, but now everything is instant so everybody makes instant judgements, so actually very little of this record has been played live. It probably means that the year after we release it the live album will be completely different… maybe better, I don’t know!

The other thing about file sharing… Well, this is a time when most people in the Western world think nothing of spending three pounds on a cup of fucking coffee… and then they have the nerve to say they can’t afford music. 79 pence for a song… I think it’s the problem with the modern era – people don’t value it because they can nick it or, if they buy it, it’s so fucking cheap that… 79 pence for something that can transform your life? And people complain about paying it, I can’t believe it. It’s so cheap… I remember when a new release was fourteen quid and now it’s eight. Is that really expensive for something that you can play over and over again for the rest of your life and when you put it on it’ll transform your mood and teach you stuff and express how you feel inside… and people think eight quid – three cups of coffee – is expensive? It’s a joke. You think music’s ridiculously cheap but that’s the modern era…

It seems that albums are treated with some level of disdain as well – yet for many bands to be judged by one song alone seems to be impossible and yet that is exactly what file-sharing encourages…

Yeah – it is a world of instant… Somebody said to me years ago ‘is the internet going to kill music?’ and no, of course it’s not going to kill music but I do think that the thing is that there is too much music everywhere. If you go into the market, there’s music; if you go to a restaurant, there’s music and it becomes a constant background. Under every drama series now there’s music; under every documentary… it’s almost on the news, almost, if they could get away with it they would – dramatic music to make you more engaged. And what this does is that it devalues it. I hate having music as background, I hate having music in restaurants – I don’t eat to music. If I want to listen to music then I want to listen to it, in which case I have it in my car or studio incredibly loud, or go out but I hate it as background. And if I’m having a conversation with somebody and there’s music on I always end up listening to the record, which means I can’t have the conversation.

So that comes back to this ideas a s treating music as disposable background noise rather than as an art form…

Yeah, yeah – I like silence! But then I have albums playing in my head… whether they are albums I’ve created myself or other people’s albums that I’ve heard so many times that they play in my head. I love that, I love the silence so that … I often think that about children in the modern day – they have so much input that they don’t have time to develop their own imagination. I worry! But I haven’t got my own children so I don’t have to worry about that!

How long do you spend on lyrics – are they spontaneous works or are they developed to the point that you’re happy with them?

Somebody asked me earlier on about my inspiration as a lyricist and the thing is I’ve lived with a poet for a long time and I’ve always been envious of the way that Jules can just sit down and words just pour out of her. Because I work really hard on it and I spend a lot of time writing a small amount if you know what I mean. I don’t produce huge swathes of words – I sit and work really hard on the words until they’re right. But I like lyrics. I like to have particular themes. I really hate those lyrics that are just about the inside of the writer’s head – generally speaking I find them very boring. I like stories and I like pictures so you’ll find in NMA, even the polemic stuff, even that’s usually got the weather in it… so you know where you are. Somebody said to me “you’re songs are like the bloody weather forecast! They’ve all got the weather in,” but that’s because when you listen to them, you’re transported to wherever it is. I love American country music for that. The music is repetitive, but the story element… I love that. I think the most basic element of human nature is to tell stories and so generally speaking that’s what we do, I think.

Which, perhaps explains why, an album like ‘Vengeance’ still sounds great even thirty years on…

I think it may have sounded more out-of-date ten years after it was released, whereas everythign’s come back round now, maybe. I think the themes don’t change because people don’t really change. The thing I think about… and I wasn’t closely involved in every aspect of the release – I tried to get other people to do it because I wanted to do the new record, so when it got mastered I didn’t sit and listen to that. But collecting the nine songs that had never been released before…. From before ‘vengeance’, it just struck me that it was a band from day one that was creatively ambitious. I think we wanted to run before we could walk, but at least we wanted to run, and you can tell that both lyrically and musically. We were trying stuff that perhaps we weren’t experienced or good enough to quite carry off but we really wanted to do something different form everybody else. And I think that’s it. And the good musicians – obviously Stuart was phenomenal, but even the drummers before Robert… both very good drummers and they really cared as well.

For all that the eighties is maligned, one of the things that characterised it for me was that you came out of the genres of punk and heavy rock, and the result was that band’s had to search far and wide for something completely new…

Definitely and this is the wonderful thing about punk – it was a cultural revolution that laid a brand new, bare landscape where everything goes. I couldn’t play guitar when we started, Stuart could play amazing, acrobatic bass, so we said OK you be the lead guitar player on bass, that’ll work! And sometimes you look back and you think hmmm, didn’t quite work! But why not?! There were no rules – it was great, it was a great era. But, to be honest, NMA we’ve stayed with punk in that it’s all about the transmission of spirit and there are ni rules, and we still adhere to that now really.

That spirit, for me, was the most important aspect to rise out of punk, as opposed to a large part of the nineties take on punk which seemed to emphasise the three-chord aspect.

Yeah – American stlye punk, for example Husker Du, is really country music done with fuzz pedals. Nothing wrong with that, but that’s what it is – all the way through to green day. It’s country. It has those roots. The thing about American music to me, and I’m going to make a sweeping stamen now, is that it’s closer to soul and roots generally speaking whereas British music tends to be more experimental, sometimes it can get too far away from soul and roots.

There’s comparatively less music being produced in Britain, though, than in America so I guess there’s less competition here?

Yeah maybe, although the thing you have to remember is that the stuff that arrives here… like Hollywood films … is the stuff that’s heavily promoted. So the stuff that arrives here is not necessarily what’s happening over there, it’s just the stuff that the big money has decided is going to sell. Usually it’s a copy of something that’s already sold, that’s how big business works. They don’t take chances very often, especially these days.

Which is one of the benefits of the internet…

Yeah, it means that bands like us don’t have to… we’re not dependent on press and radio and stuff like that. It means that bands like us can exist without and we can put two fingers up at the press and the media. And we have done… unfortunately in return the media put two fingers back up at us. But we’ve done whatever we want for thirty-two years. I can’t think of another band that have never had a hit single in any country, no top-twenty single in any country ever, that don’t belong to any kind of genre, that’s had a thirty-three year career. And the genre thing… well I remember in 2010 we managed to play a straight folk festival, a hippy festival a gothic festival and a metal festival… all with basically the same set.

So the generational appeal of NMA is, perhaps, the spirit and lack of conformity?

Yeah – somebody mentioned to me about the fact that we were using acoustic guitars and, you know, there were acoustic guitars all over ‘vengeance’, or we get comments that it’s not political enough and, again, not every song on ‘vengeance’ is political. From the very beginning we were just going to do whatever we wanted to do. I was talking to someone from our old EMI days the other day and he was saying that we were a nightmare! They would always try and tell us how to make money and sell records and we would never do it – but then that was never our primary objective. We have to make a living I suppose, well we don’t have to, but it’s nice to make a living from music, but that was never our primary objective – being successful or selling records – our primary objective was doing something that we thought was great.

Yet, for that, you have a group of passionately loyal fans…

Yep – bless ‘em all! And they… the interesting thing again is the belief that there is a hardcore of fans who have followed us since the beginning… far from it! The interesting thing about the travelling following is that it regenerates every three or four years – there’s a whole bunch of new people and then those travelling fans all have got different eras that are their favourite eras of the band, so some of them will believe we’ll never top ‘vengeance’ and then there are a whole new lot form the last ten or fifteen years and the old stuff is not so interesting to them as the stuff we’re doing now. I do think that we’re very lucky because we’ve never had a hit single in any country ever, there’s nothing we ever have to play so we’re not prisoners of our back catalogue. I can’t think of anyone else of our peers that can… you know we’ve just done this ‘vengeance’ thing and, actually, art Christmas we did play a couple of old ‘vengeance’ songs but I remember a couple of Christmasses before we did a big show in Cologne and someone asked me how many old songs we were playing and I realised that out of a seventeen song set there were two from before 2000, and the audience was fine with that – they’re coming with us. Or, if they’re not coming with us and they’re secretly standing at the back of the hall wishing that we’d only play their favourite song from 1936 or whenever it was written then they’ve probably at least accepted that we’re not going to!

With such a career behind you, from everything you’ve said today it seems that the ambition is still very much there, what comes next?

We’re doing a couple of shows in the UK in May and then bits and pieces but nothing major because obviously there’s no record yet and then the record will come out just before or just after the summer and we’ll be doing a proper album tour from the Autumn. Don’t quite know how we’re going to do it yet… We’ll see.

Musically?

Yeah – one of the reasons we picked Terry, the new bass player, is that he likes playing drums so at the Christmas shows we were able to do the two drums thing more. And we’ve done that before with Nelson, but he never really enjoyed it whereas Terry actually really likes hitting drums.

It’s a great, primal thing to do!

Absolutely, yes – so there’s a lot of layered drums on the new record so, we’ll see. I just… everything feels pretty good for us at the moment and I think it’s an interesting record. Whether people like it or not in the end, is less important than the fact that we’ve been up a lot of new creative paths making it, and the atmosphere within the band and around the band is really good, and I thought the shows we did at Christmas were really good and we bought back the spirit of the Falklands and 1984, partly because we’d been reminded of their existence by this re-release, and it felt really good and quite modern.

That brings me to the end I think

I bet it does!

It’s been a pleasure and I’ve tried to keep my train of thought…

We have really talked a lot about the ‘vengeance’ thing – but then it is what it is. It’s the beginning of an interesting band.

And not just the beginning for you, but your fans as well

Yeah – I think for a lot of our fans, they got all that material before, well except for the nine songs that were never released. Most people have never heard those songs and, yeah, they’re quite good songs?

Was it good to revisit them?

Yeah – I sat and listened to them and I thought ‘that’s a promising band’ [laughs]

Any final words?

No, not really, I mean this seems to be a bit of an issue with us. In these days of Facebook and Twitter, we’re meant to keep up a constant litany of conversation for people who hang on our every word, but actually, we haven’t got much to say of any great interest beyond what we make. So the things we want to say are there in the music – that’s where they are. Beyond that there isn’t much to say.

It must be difficult to find new ways to emphasise the same point

I think there are always problems with this. As I said I met this guy with whom we used to work at EMI and the thing is that the conversations I have are essentially because I’m trying to sell something and I… can’t be bothered!!!

And with that we say thanks and Justin is gone, marking the end of one of the most interesting and free-ranging interviews I’ve had the opportunity to conduct.