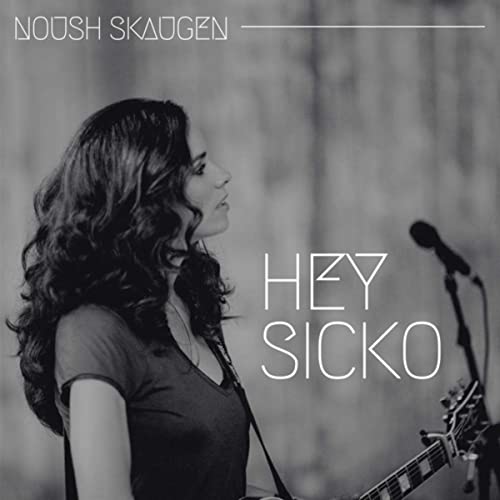

Given Noush Skaugen’s profile as both an actor and musician, I wasn’t sure what to expect when I was given the opportunity to discuss her fantastic new album, Hey Sicko. Any nerves I might have had, however, were soon dispelled as Noush offered a friendly greeting and dived right into the interview. Warm, friendly and prone to going off at a tangent mid-question, Noush bubbles with enthusiasm for her experiences in making the album – especially the opportunity to work with the legendary Michael Beinhorn (Hole, Soundgarden, Chris Cornell) – and her passion for the music shines through as she discusses how important it was to her to make an album and not simply a collection of songs.

There have been a lot of comparisons made between this album and artists such as Hole and, for me at least, the Manic Street Preachers; so, I wanted to start by asking your thoughts about the influences on this record.

Yeah, for me it’s always interesting as to how people are going to receive it because I know every writer… we don’t think how the audience is going to receive it, because then we’re pre-empting something. I think the best albums are made when singer/songwriters are just doing what they want to do and if people love it, they love it, and if they hate it – honestly, I don’t care. As long as we’re following what we are supposed to do, if that makes sense, and doing the best that we can and what’s coming from our hearts and… fuck everybody else basically! [Laughs]

But it’s true, as an artist you’re always thinking about the manager, the audience, the label, the pluggers… and they all want to get their noses in and have opinions and everything. I’ve always been an independent artist, but obviously I’ve had managers – really, really good managers – I had Robbie Williams’s manager for a while… but yeah, it’s just a whole different experience because I’m used to doing things and captaining the ship, so to speak. So, it’s kind of trippy, because my mates who know me in the business, they think I’m unmanageable – I know what I want, I know how I want to do it. It’s hard for me to find that partnership where people understand where I’m coming from. On an artistic side, though, I’ve never had an issue with that. I always find musicians that are vibing with me and I’ve attracted the right people to come into the project.

Yeah, so Hole… Hole did not influence me – I love Hole, but it was kind of ironic that Michael had literally just come off doing Nobody’s Daughter and then came to do my album. And Celebrity Skin, yeah, I really only got to listen to that once I was working with Michael. And you know, he has a lot of references, having worked with Courtney, Soundgarden, Chris Cornell… and obviously every artist is different and he’s very much about getting the best performance out of the musician – out of the collective of the musicians as a band. I always wanted to have a band – it just happened that I became solo. Honestly, I tried my hardest to be in a band, but I think it’s tricky when you’re writing your own material. In a band, everyone wants to feel like they’ve been a part of the writing process, whereas I write all my own songs, and then I bring it to the musicians on an acoustic or electric guitar… very occasionally on piano, but that sounds very different – that’s a different vibe and this whole record was written on guitars. It’s very rock oriented.

So, yeah, I tried, but I think they all want (not so much a piece of the pie) they just want to be part of the writing process and I think that’s why it’s not happened… but never say never! I might join a band one day, but I think that’s what makes an artist. And Michael is there to get the best, because if you don’t know… then no one else does. It’s like a director on the film set – if they don’t have the whole vision of how it should be then… but they should still be open to surprises because surprises are the best – it could be something you’ve never thought about and then it turns out to be amazing! And that then inspires you to write another middle eight or write out a new song that comes from that inspiration, so it’s definitely a collective process….

Sorry, I went off on a tangent… [Laughs]

I really like those references, because it’s great to hear what other people hear as influences. But yeah, the marketing people have their ideas, and I just do what I do.

The thing about being a singer / songwriter and the band thing that you mentioned is really kind of crucial, I think, because it can be very hard to let go of any aspect of a song that you’ve worked on independently – did you find that to be the case – that you could get a bit protective over your songs, or are you happy to kick off ideas off Michael or whoever?

Oh, 100% I love collaborating with good people. And everyone on this album was of an outstanding quality. I mean, Michael is a genius… but honestly, when I told the musicians we were doing a record with Michael, they literally shit their pants. They were rehearsing for months. I got my musicians from Nashville, because when I did Lost and Found I did that in Nashville, in a whole completely different way. I had Keith Urban’s musicians, I got charts and they played it out like, you know, the first time they played it, was literally like they’d been playing it for years. They were so amazing. But, you know, for me Lost and Found is a great record and I’ll always stand by it, but it was more of a pop-rock record, so to speak, because of that Nashville… that’s how Nashville records are made. They’re made by amazing musicians who get in the studio and play it once or twice and that’s it – it’s very… more of a sterile environment.

And I recorded at Blackbird Studios – it was amazing. You know, go and get coffee in the morning and bump into Jack White in the coffee shop. Nashville is just that very cool place and everyone’s a musician.

But it’s a very different vibe for this record. I came off that record like I was still searching for what I wanted to do, and I knew in my heart what I wanted to do – I wanted it looser, you know – more rock ‘n’ roll, more Keith and Mick. So, yeah, it’s not perfect on the guitar, there are little surprises. The beat might be slightly off, but that’s what makes the magic of it. I wanted it to feel live, even though a lot of the first record was recorded live as well, it was just the musicians. But anyway, yeah, I met my musicians when I was doing that record and I lived in Nashville for a year or two, on and off, so I we toured Lost and Found and I was just loving how they played and it was just a really good vibe and I got to know them really well, because we all stayed in one hotel room – me and four guys… I won’t go into detail, but you can imagine we became pretty close with smelly socks in my face [laughs] and sleeping on couches and, you know, all good times!

So, when I final got in touch with Michael and he wanted to do the record with me, I gave them a call. And obviously he’s in LA and I was back in London at that time and that’s how that happened. I got musicians that I knew were really good and I had a good vibe with and a connection with and then Michael on top and I just hoped that it would work. So, yeah!

I remember you saying that it was really important to you that this album was live, with no autotune, and I think you do lose so much of the soul of the music when you start correcting things in the computer… you lose a lot of the heart

Definitely and I think listeners don’t realise it, because they’re not musicians, but they just feel there’s something colder about the sound of it. It just doesn’t resonate the way a live record would, when you put on a vinyl from back in the day – the Stones, or Pink Floyd… you want to sit down, lie on the floor and light up a joint and listen to the whole record and watch Alice in Wonderland (I’ve done that by the way – you turn off the sound) but yeah, it’s the sound that resonated with people but they can’t put their finger on it and then you start… I mean, everything is done with Pro Tools on the computer nowadays, and that’s just the way it is, unfortunately, but you can still record very much analogue with the equipment and that was paramount. I did not want autotune and that sort of thing.

There was very little autotune on Lost and Found but I didn’t want it to be clean or perfect – that was my perfect record! And now I wanted this to be full vocal takes… which was… I didn’t quite realise what I was getting myself in to. The vocals were a pain in my backside for the whole record but I’m not the only one, apparently – Courtney was the same! Yeah, and the drums, I think with Nobody’s Daughter, they did drums for a year and a half and then, at the end, it just wasn’t good enough and they had to scrap the whole thing and Universal had to fund a whole new session… [pauses]

Any way…. Michael is extremely picky and good on him – he knows what’s good. He doesn’t want to put anything out… put his name to anything that’s not up to par. So, yeah, it was tricky. Definitely. The vocals – I recorded the vocals in three different places. We did it in the rehearsal studio in the valley, and then we did it in the other studio and then we came back to London and did some more and then back to Paramount in L.A. because they still weren’t good enough. It was like a whole shebangle! So, yeah, it was an interesting journey, [laughs] but we got there in the end.

Doing vocal takes is such an ambitious move. The pressures on a vocalist to get a really good take… any single slip, if you’re not prepared to punch in it’s actually really hard, especially if the band is sat in the control room watching you… Did you have any vocal coaching or technique that you could fall back on to help with that?

Um, I mean I’m a classically trained musician. I play the flute and the sax, and I did like the orchestra stuff. But, as a vocalist, I had a few lessons back in the day but not really. I didn’t want to have that trained voice, so to speak. Obviously, I wanted to learn how to breathe properly because I have quite a raspy voice and playing rock music you’re going to do shows and tours night after night, you have to learn how you’re going to manage that because it still goes on the vocal chords… [sotto voce] so, you drink a lot of whiskey and tequila… [laughs] It’s true! I mean not a lot, but before a show, whiskey does warm up your vocal chords but yeah, be careful! I am, especially if I’m playing as well. I don’t care about the vocals, I’ll be fine, but if I’m playing… it’s tricky.

[Pauses to think about the question…] Yeah, with the band watching, that’s the whole thing. Michael realised I couldn’t have the band watching from the control room. I wasn’t able to get into myself. And also, I had to have the guitar with me, he realised that as well. Singing and standing up… it just took something away from my vocal, I don’t know why. But, like I said, that’s something I would never have realised. That’s what a good producer does – he tried all sorts of things – and it’s not something that you necessarily know why it’s working or not and it’ll do your head in because you keep going at it for ages and then it gets in your head, and once that happens it’s a nightmare. You’re like “Oh my god I can’t do this!” So, yeah, they left the control room, and Michael was how he was with Chris – he basically showed me how to record and what buttons to press – and that’s how I did a lot of the vocals. They all went for lunch and I was doing my vocals!

I think it’s quite hard – doing vocals is quite vulnerable anyway and being sat at a microphone when you’re used to singing with a guitar – it can be very difficult to give it that oomph that you’d give it on stage because you don’t have that feeling to kick back on. It’s very challenging.

Exactly. I think every singer is different, obviously. But putting a guitar in my hand, made me feel more like I was on stage and more of that energy. But it’s kind of weird, because you have musicians and the producer just staring at you from the control room and it’s a whole different ball game. It’s like “bugger off guys! Go and do your thing!” Yeah, it’s a very different scenario, I think. You’re not performing for them. You’re digging to the depths of your soul to get the best performance that you can and doing four takes at the same time. I definitely set myself up!

Do you find you tap into your experience as an actor as well, when you’re doing the songs, or does it come from a more personal place when you’re trying to inhabit the lyrics?

Um, yeah, it’s completely different. As an actor, I’m given the lines, I’m given the script and obviously I’ll have a connection to the scripts, and I’ll do my… I won’t go into actor lingo, but I’ll relate it to myself, so it becomes a part of me, and I become the character. Whereas the lyrics always come from me. If I collaborate, like with Nik Kershaw, the lyrics will always come from me. He might tweak something here or there and say something sounds better. But I think if you want to be an artist, you have to have a succinct album as well. You know what you want to say. That’s what I wanted. I didn’t just want a bunch of songs and fillers. I wanted it to be like a classic record that will stand the test of time. And that’s why it took so long – the production and everything. It was just… it’s not an easy thing to do. So, yeah, the songs definitely come from me.

But musically, if I’m writing we’re just throwing around a few notes, but I’m basically coming with a lot of it done. Then we’re open to good ideas, because obviously I work with great people who have amazing ideas. It just depends on the session. I’m always open to whatever. When you work with that calibre of person, you’ve got to be open. But you know, when they do give their ideas and you still believe in the original lyric you had, then I still stick to my guns. But I’ll listen, I’ll try it – we’ll do demos and try it.

One of the big skills, and something that’s been a bit side-lined by streaming, is to make an album rather than a collection of songs. But the big challenge is not only to create the songs, but also the sequence and flow so that the album runs from start to finish and, also, potentially within that vinyl sequencing of side A and side B – the big launch song that kicks off the second side. Was that something you had in mind right from the start?

Absolutely. Yes, I wanted to create an amazing album from start to finish. I remember, not that Alanis was an influence on me, but there were seven singles off Jagged Little Pill – it was just such a great record in terms of that and I just wanted that with this. I wanted every single song on this to be able to be taken away from the album. I didn’t want any fillers – if it wasn’t up to par, we’d go back to the drawing board.

And that’s exactly what happened. I arrived with over 100 songs and Michael was like “yeah, you’ve only got eight!” [Laughs] So, we couldn’t even get the musicians over from Nashville until I’d written the other ones. So, that’s what happened. It was just me and Michael for six months pretty much. I was in Venice and he would come over and play me like Indian music just to try and find what I wanted to say with this album. He’d always refer to Bruce Springsteen, who very much produces his own albums – “it’s your vision, you’re the captain of the ship, you know the purpose of the album.” Because there are so many producers who will just come in and put their stamp on it and you know it’s done by that producer and they haven’t taken into account the artist… but Michael’s the opposite. He wants to support you to find your voice and what the album is going to be and the world you’re going to bring people in to. Very much like a film, so I guess I do bring my acting experience because I want it to be like watching a whole film. It is an experience – listening to the album from start to finish. And yeah, if people want to listen to the songs over and over again, they can… but it was very much thought out.

Lyrically, as well, the way that the album takes you on a journey and quite early there’s the pairing of Buried in Vegas and hey Sicko which kind of sound like the experience of a young actor in America for the first time – is there anything in that?

Um, again, that’s really interesting how people receive things. I always like to leave things ambiguous so that listeners can make the song their own and make their own experiences from it. Once it’s out there – it’s no longer yours, it belongs to people.

Buried in Vegas, I guess that was very much about my experience of going to L.A. It was a combination of life experiences, really, just going to L.A. and being very naïve. And Vegas… Just the States in general. For me, Vegas epitomises the whole of the States. It’s like flashy, dreamy and very much superficial. We think, growing up in the UK, that Hollywood and America is like the dream and then we realise that it’s not that different to the UK. It’s kind of the dream, built up through Hollywood, but when you actually live there, there are huge differences in people, wealth and class. There’s a not-very-pretty side to the States and Vegas, where everything is kind of dirty behind closed doors. What you can do, you have these huge amazing hotels with all this money being thrown around and then you have all these other people who are just trying to live their lives. Yeah, so it was kind of a combination of that.

Hey Sicko, is actually nothing to do with that. It’s my conversation with cancer, because I lost my mum to cancer when I was a kid. It was more like, not from a bitter point of view. It was very much just wanting to have a conversation. And yes, there is anger in it and there is darkness, but it comes from a more mature place. More of a “who are you?” “why are you doing this?” back and forth – and that’s what I wanted it to be.

That was one of the last songs I wrote for the album, I’d been playing and playing and playing, and then I couldn’t play anymore, and I’d go for a walk on Venic Beach, go to the drum circle and get my head out of itself, and I wanted it to be ambiguous for other people. It could be someone who’s giving you shit, or someone who’s hurt you… just someone you want to have a conversation with. But yeah, everyone can bring their own interpretation to it – that’s why I never say “cancer” or what it is that I’m speaking with. Good song-writing never does that anyway. We’re always very much looking at the poetry of it and [pauses] Bob Dylan’s the king!!! [Laughs]

I think that’s a really good point, when you’re writing lyrics from a very personal place, the challenge is to pitch them so that they can become universal and something that other people run with and I don’t think that’s an easy thing to do at all.

No, it’s not easy. It requires work and I wanted to juxtapose the sadness (well, they’re not really sad lyrics – they’re more “what the fuck, dude?”) but I wanted the music not to be angsty rock, like Run Baby Run. I wanted it to be more like a conversation, which is why it’s more of a ballad. It’s a more intimate song, but it’s not an angry song. It’s just a conversation, but yeah it is hard to do that and it takes work, refining and refining.

Do you ever find, writing lyrics, you have to work through to get the poetry of it to fit with the music as it comes together?

It depends on the song really. Some songs just come really easily. Run Baby Run came super easily – I think it was ten or twenty minutes to write! Other songs require more finesse. Hey Sicko needed more finesse because it’s a different subject matter, a different melody line – yeah, there’s always the question of whether to put a seventh or a ninth in; or do we skip the bridge and go straight to the chorus… so, I tried a lot of different things.

And a lot of it is also working in the studio with the musicians in rehearsal. Because we were rehearsing for months in a studio in Hollywood, and a lot of the structure of it changed, just through rehearsing with the guys, because they all come up with riffs or basslines or drum patterns which result in changes. So, you know, you’ll increase the intro section…. and everyone’s like “you can’t have intros anymore. You can’t have guitar solos anymore – no one will play it on the radio!” My radio guy… everyone’s just asking what we’re doing and for me, it’s like “Pink Floyd did it! They had an eight-minute song on the radio!” and then they point out it was twenty or thirty years ago, not now!

But I don’t care. For me, it’s about the song and I’m not going to write a song just so it’ll get played on the radio just for some dude to tell me it’s not made the C list or B list or whatever. I don’t really care, but the thing is you have to do what you do, and good music will always burn through anyway. Radio’s not that important anymore really, Spotify is where people play it, so that’s what matters to me, really.

What you were saying about the dogma of radio – it always surprises me that that’s still a thing – “you have 10 seconds to get to the hook” – it’s like, oh man! Come on!

Yeah, and it makes everything sound the same – if you listen to the radio, it’s all the same songs with the same structure and the same people writing them with all these people and lots of crap… I mean, there are some really good pop songs, obviously, but it’s the same kind of homogenous world and obviously there’s an art form to that, which I respect. But it’s not what I do. Definitely not. And if I want to put a guitar solo there, it’s going to be there. Whatever honours the music, if that makes sense. It’s not about me, it’s not about the radio…. and once you get into the studio with the guys, like a beast, it takes its own form and the song just kind of screams out what it wants and what it needs. So, yeah, refining lyrics, it depends on the song.

It’s an important distinction – when you’re working with people who are very capable musicians, you get people who want to serve their own skills whereas serving the song is so much more important, [particularly if you’re writing an album that flows as we’ve already discussed.

Yeah, it’s really, really important. You have to know that in the studio. Obviously, you have egos, and everyone wants to get their piece in. That’s why it falls down to working with the right people and Michael’s great because he manages a lot of that as well. I have great people I’m working with and our engineer as well was great. Everyone was very much of the mind that they wanted it to be the best possible music rather than serving themselves.

But yeah, I did have an issue with my bassist, so I did have to send him back to Nashville. Yeah, I mean, it’s tricky when you’re friends with people as well, because originally it was the drummer, guitarist, and bassist and then, once we got into the studio to record the drums and the bass, we were all playing (I always play with them, all the time, on guitar) and so they had the vibe. Then Michael bought me into the studio sound room, and we just listened through and it wasn’t good, because the bass was completely off.

And the more he tried to get it right… you know how a bad egg can kill the vibe and everyone feels it? That’s exactly what started happening. So, he’s a friend of mine, but I had to put that aside because it’s about the album and the music. And when Michael played it to me, it was like – “yeah, you’ve got to send him home.” It was the hardest thing I ever had to do, and it was worse because I had to do it in front of everyone, so that there was no misunderstanding. – no: “oh, she said this to me…” So, there wasn’t any gossip, we had to listen through it all with everyone there…. sometimes it’s hard to accept that you’re just not ready for that, because Michael did push us really, hard. Really hard, like everyone. That’s why my vocals were done over two years in various locations around the world, because they weren’t good enough. You’ve got to have the stamina to take that.

My drummer was in the studio rehearsing for eight hours, and we’d be off for a beer on the beach, and he’d stay for another four hours. I think, because we were working with Michael, they wanted to do the best that they could do, but the bassist just wasn’t up to it. So, then Stanton, who also did guitar, did bass and he did a phenomenal job on the bass. Phenomenal. I was so happy with that. That’s some of the comments I’m getting on the album – the bass is amazing. But also, that’s Michael – his bass is amazing – like Celebrity Skin – the bass is amazingly recorded. So, yeah, it’s a challenge and an interesting journey.

My final question (and it’s depressingly generic) is that the album is coming out in a middle of a pandemic, that is having such an impact on people’s ability to make music and to share it. Have you got any promotional approaches that you’re taking to try to get the music out there?

Um, yeah, well – I’m doing a live set with Original Rock Fest in the middle of November. That is the last thing that’s in the pipeline. That’s the only thing we can do, which is super-frustrating and one of the reasons why people were asking if I really wanted to release the album right now. But I don’t think this is going away. Glastonbury have already said 2022 and I don’t want to sit on this. I feel like people need music, and if I can’t tour live, then so be it. I’ll just do as much when I can and how I can. If I can do live set, or festivals that are online – a lot of that’s happening. PRS did that thing recently, with people zooming and doing their sessions, so I think they’re just navigating the way in the music industry as to how we’ll still connect with people.

Obviously, it’s not the same. I’m going to be doing my live set from here with an acoustic guitar, so it’s not the same. The record is not an acoustic record, so it’s tricky to do that. We have to do what we can to connect with people and get it out there. Hopefully… well, who knows what will happen, but it doesn’t look good next year for festivals, with Glastonbury postponing, I think everything will follow suit, although maybe Download… We’ll just have to see – no one knows. Not even Boris knows!!! It’s a shit-show! I think we’ve just got to do what we do and as much as we can and when things open up again then we can get back on the road and do some shows… it is frustrating though, because I’d love to play this live.