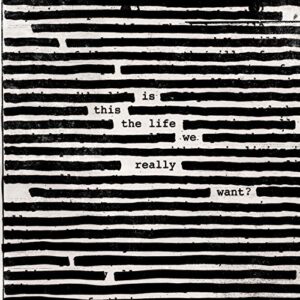

Roger Waters does not need to make any new music Has not needed to, in fact, for over thirty years. At least from a financial perspective. From an artistic perspective, the man who admits to being “still afraid” as the voice collage of ‘when we were young’ emerges to the sound of ticking clocks in a nod to ‘Dark Side of the Moon’ and a seeming countdown to our own extinction, quite possibly did have to make this record, fuelled by an insatiable muse that has always proved to be better fed at times of turmoil. Nonetheless, even from the man who made the Thatcher-destroying ‘Final Cut’, ‘is this the life we really want’ is a surprisingly visceral assault upon the ruling classes that stands as what is arguably the most musically consistent work of Roger’s solo career. Certainly, all the hallmarks are there: sampled extracts of war and noise, lush, orchestral-enhanced soundscapes and that bitter roar that sounds like the hell-bound child of Bob Dylan and Tom Waits – it’s a Roger Waters album alright, but it packs more of a punch than any album Roger has put his name to since ‘Animals’.

The album opens with a brief musical collage. Entitled ‘When we were young’ it’s tempting, as it is on ‘DSOTM’ to listen intently, desperately trying to pick out some pearl of wisdom from the cascading voices before the track segues into the acoustic strum of ‘Déjà vu’, a gorgeous rumination that sees Roger raise the hypothetical issue of what he would have done had he been god juxtaposed with a similar question of what he would have done had he been a drone. Roger’s eye for detail has not deserted him, nor has his gift for mordant satire, but what really hits home is how the savagery of the lyric is set against Nigel Godrich’s achingly beautiful strings. It’s a brilliant opening, richly textured and whilst the themes that dominated Rogers’ earlier works remain fully intact (“the temple’s in ruins, the bankers got fat”), what was once worryingly prescient has now become normalised in a world truly run by a neo-liberal agenda, stripped of humanity in favour of rampant capitalism. Opening, as is Roger’s wont, with the warm tones of a grand piano overlaid with samples, ‘the last refugee’ recalls ‘Perfect sense (part 1)’ with its hypnotic beat and hazy synth. A heart breaking song both musically and lyrically, ‘the last refugee’ sees Roger’s wonderfully ravaged voice edging into David Bowie territory, particularly in the higher register, and the effect sends chills flooding down the spine. Things take a distinctly darker turn with the synth stabs of ‘picture that’ recalling the retro-futurist soundtrack of ‘A Clock Work Orange’ crossbred with ‘welcome to the machine’ and ‘Shine on you crazy diamond (parts vi-ix)’. Roger sounds positively enraged, and it’s remarkable to hear the vitriol in which his vocal is steeped as the music stacks up behind him, growing into what is possibly the most overtly Floyd-esque work of Roger’s entire solo career. For a Floyd fan it’s a moment of awe, but it’s also devastatingly current, opening up the possibility of Roger Waters, at 73 years of age, finding a whole new audience at a point where most artists would be winding their career down. Heading into introspective territory, ‘Broken bones’ captures the apathetic mood of the current generation with Roger intoning “who gives a shit anyway?” whilst pointing out how different it might have been post World War II if only consumerism hadn’t been embraced with such single-minded ferocity. The first half concludes with the title track, a brutal dig at Donald Trump set to a beautifully somnambulant backing that sits somewhere between Rogers’ own illustrious past, Radiohead (with whom, of course, Nigel Godrich has worked extensively) and Massive Attack. It’s a masterpiece, a searing indictment of modern times that holds a particularly unflattering mirror up to contemporary society.

Segueing form the tortured scream of “it’s normal!” that concludes the title track, ‘Bird in a gale’ is another synth-driven track that builds a sense of deepening disquiet with its carefully-sourced samples painting a picture of a soulless, corporate society before spacey guitars emerge and Roger appears, screaming in the darkness with a ferocity that harks back to ‘The Wall’ as, indeed, does the music with its echoing vocals bring back the harrowing horror of ‘is there anybody out there?” We are allowed some respite with ‘the most beautiful girl’, a track that manages to sound like Radiohead covering latter-day Bowie, offering a moment of gentle reflection before Roger, miraculously, returns to Pink Floyd’s heyday with the funk-infused ‘smell the roses’. Once again it edges into ‘the wall’ territory and yet it also draws on the life-time of experience that Roger has accumulated since that epic work, and the result is mesmerising. With its strummed acoustic and stark atmosphere, ‘wait for her’ is perhaps the closest thing on the record to anything from ‘the final cut’, and it is delivered with both passion and pathos by Roger, Nigel sensibly stripping back the layers of orchestration to the bare minimum to allow the power of Roger’s words to emerge unfettered. A short segue, ‘oceans apart’ flows into the album’s elegiac finale, ‘part of me died’, a pretty piece of music that lyrically sounds like the monologue that plays over and again in the head of Nigel Farage and his vile cronies. Numb, nationalist and nasty, ‘part of me died’ seems to be a eulogy for a society on the brink of self-immolation and it breaks the heart with its synth shimmer and gentle piano. It’s the perfect end to an album that rages against the dying of the light in an articulate manner that seems to be currently lost amongst the younger crop of artists from whom you’d traditionally expect such a protest to emerge.

Can it really have been twenty-five years since Roger had something of such import to impart? It seems tragic, on the one hand, that so much time has passed in the absence of new material from Roger (‘Ca Ira’ aside), but what a return. Beautifully crafted, this is easily the most powerful solo work Roger has ever attempted and the themes that dominate the record have clearly lit Roger’s long-dormant creative fuse, causing him to dig deep and deliver a record that seems to collate the very best moments from the run of Floyd albums that starts with ‘DSOTM’ and ends with ‘the final cut’. That’s not to suggest that this record equals Floyd at their very best. One thing that is missing is the liquid lead work of Gilmour and the emphasis here is very much more on the symbiotic relationship between music and lyrics that has always lain at the heart of Roger’s work. That said, the musicians that Roger has assembled do a fantastic job of creating the imaginative sonic canvasses with which Roger has always worked and the result is an impressive, ambitious record for which we should simply be grateful that Roger cared enough to make. For Floyd fans and newcomers alike, Roger Waters has delivered an album that casts a weary and frequently horrified eye over the societal changes of the last thirty years and whilst the view is not pretty, it most assuredly is compelling. 9