Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness stands as one of the most ambitious double albums ever released, and a milestone in the career of The Smashing Pumpkins. A sprawling, 140-minute set (with almost the same runtime again in the myriad B-sides found on The Aeroplane Flies High), it was a magnificent creative endeavour, albeit one that all but broke the band. Later, the Pumpkins would explore electronica with the underrated Adore, and overblown prog-metal with Machina, before calling it a day altogether, bowing out with a mammoth farewell tour in 2001.

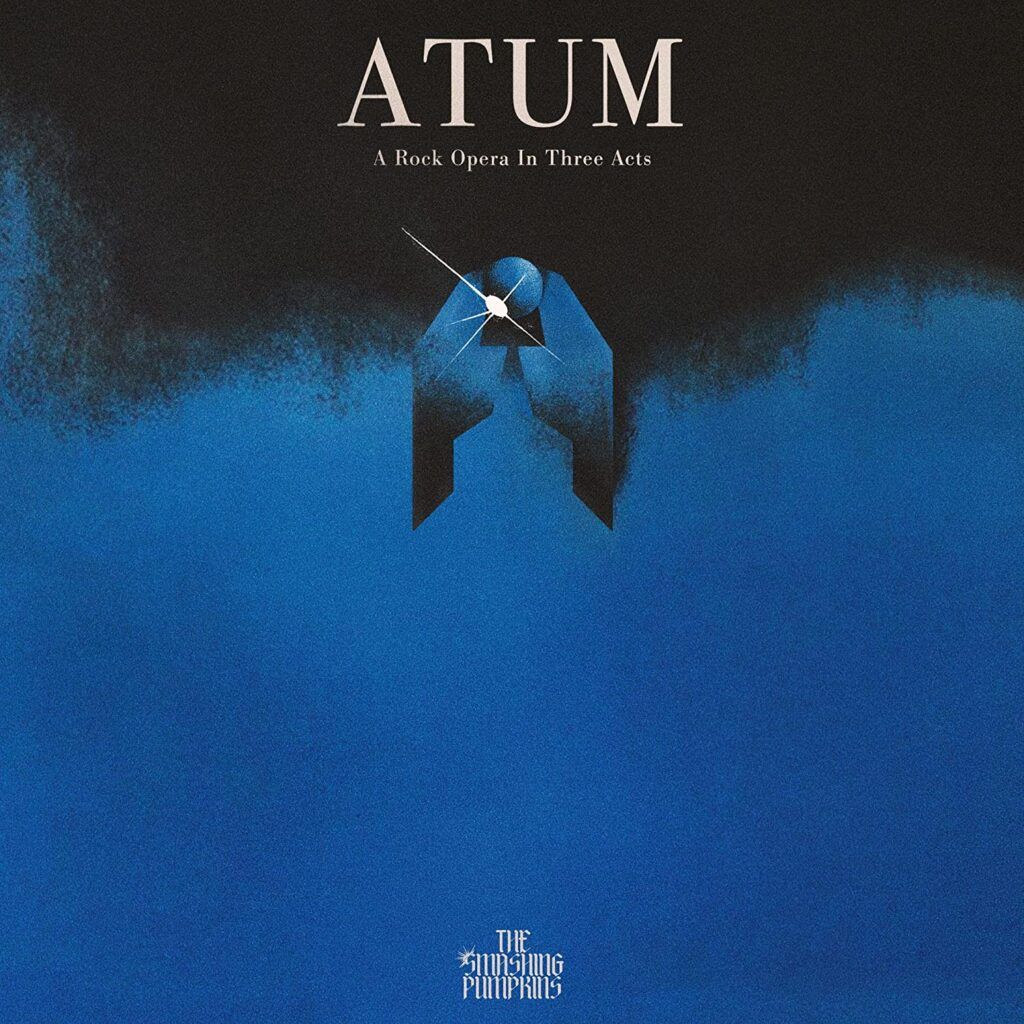

The band’s return proved somewhat bumpy. Initially centred around Billy, similarly ambitious projects were announced, only to stall part way through; and, despite some excellent moments, it took the return of powerhouse drummer Jimmy Chamberlin and ethereal guitarist James Iha to stabilise things. Of course, this being the Pumpkins, there was still room for the unexpected and, rather than consolidate the advances made on the frequently excellent Shiny and Oh So Bright, the band took a sharp left turn with the hard synth manoeuvres of Cyr. Of course, with hindsight, it is now clear that those two releases were only ever intended as an entrée and, with Atum, Billy has drawn from both to craft a three-part rock opera that serves as a sequel to Mellon Collie and Machina, while standing as a towering achievement in its own right.

Naming Atum as a sequel is arguably something of a bold decision, given the esteem in which those albums are held, and there are moments where the album doesn’t quite attain the lofty aims its creator had in mind, although it is still one hell of an achievement, not least because few artists care enough to even attempt so Herculean a task. The result, clocking in at a suitably epic 130-minutes and spread over three acts, is not something easily digested in one sitting not least because it lacks the sublime variation found on its predecessor. That said, it does capture some of the sweep and scope of Mellon Collie and, despite its flaws, it deserves credit for being its own entity and no mere re-tread of past glories.

Packaging:

Packaged in an eight-panel digipack, complete with concept drawings, and with a custom slip bearing the band’s logo, Atum is otherwise a simple package. Most interestingly, the included booklet eschews lyrics for a libretto, underscoring Billy’s operatic ambitions and, for the first time, laying the plot bare. When you consider that Billy expected fans to interpret various “shards” in order to understand the labyrinthine Machina, it’s clear that, this time out, he’s willing to do the heavy lifting in the hope that fans will simply enjoy the journey.

Act 1

The first act proves to be relatively short, with the eleven tracks clocking in at just over forty-minutes, although that’s not to say that there isn’t room for experimentation. The album starts in Bowie territory, circa Low, with the squelchy synths of the title track giving way to Floyd-esque leads and the massed backing vocals of Billy’s choir, the Seraphim. In many ways, it feels like a continuation of Cyr, filtered through a Roger Waters lens. It’s a grandiose scene-setter but Butterfly Suite soon sets things properly in motion, as Billy engages in a romantic flight of fancy, playing the part of June, serenading Shiny’s ship up in the heavens, although there are some surprisingly crunchy guitars as it progresses. Those guitars remain for The Good In Goodbye, which is based around the sort of riff that many assumed Billy just didn’t write any more. Layered with sparkly lead and nailed by Jimmy’s rock-solid beat, it’s a cracking track and one of the first disc’s heaviest moments.

Having allowed the guitars a workout, the band head back into Cyr territory with the heavily arpeggiated Embracer, a swooning electro-ballad that paves the way for the similarly synth-heavy With Ado I Do. Initially a slow and somewhat lacklustre piece, it picks up as the band introduce some humongous beats, but it just feels like they’re trying too hard to tap into modern production trends and it’s a relief when Hooligan brings the guitars back, more effectively integrating the synths into the band’s sound. Better still, Steps in Time is built around a snarling riff, although the synths sometimes overwhelm the mix here, cushioning the blow where no such safety net is necessary.

The strum of an acoustic wrongfoots the listener on Where Rain Must Fall as the track once again heads toward the wheezing synthscapes of Cyr. However, by this point the production starts to overwhelm and, despite the disc’s brevity, you can’t help but long for something a little more stripped down. That said, the hard-disco stomp of Beyond The Vale – part Muse, part Depeche Mode, showcases the band’s current sound at its best. In stark contrast, the frankly horrible Hooray! is filled with squelchy noises and whimsical vocals, although eighties-infused closer, The Gold Mask leaves things on a better note.

Overall, Act 1 has a number of excellent moments, often showcasing the post-reunion Pumpkins at their best. However, it does also succumb to the temptation to slather on the synths, which undermine the guitars and lack the necessary flair to soar in their own right. Highlights include The Good in Goodbye, Hooligan and Steps in Time, but it is the weakest of the three acts, offering a strong foundation to the album, but also struggling a little under the weight of the concept.

Act 2

After Act One’s opulence, Act Two is a significant improvement. A heavier, sharper set, it may start amidst the airy synths and sample birdsong of Avalanche, but it soon picks up the pace, Billy offering up a more organic ballad than found previously. While the synths are still present, they’re subordinate to the guitars here, and the track has a classic Pumpkins vibe to it that proves surprisingly irresistible. Then there’s Empires, a prog-infused track that plays out like a distant cousin of Zero with its grinding riff and taut drums. Similar to Embracer, Neophyte is a starry-eyed synth number, and it works well, with a swooning chorus and strong backing vocals. Next up, the heavily processed drums of Moss underpin a heavy riff to exude a sense of menace, while Billy and his backing choir excel here. Less successful is Night Waves, which is nice enough, but over-reliant on synths. Strangely, Space Age, which is also heavily awash in synth patches, feels more natural, as it’s a slower, lighter piece reminiscent of Adore as opposed to the more pop-heavy vibes exuded by Night Waves.

The middle of the act remains very much in the dreamy vein of Space Age, with the slow, ethereal Every Morning a subtle piece that moves the plot, rather than the album, forward. It does eventually attain a momentum, developing a gentle melancholy not unlike mid-period Cure, but it’s overlong and it’s a relief when the snappy synth pop of To the Grays emerges as an early-Depeche Mode piece, with Billy tapping into the naivety of People Are People. Better still is crunchy single Beguiled, which has a nasty rock-disco stomp and plenty of attitude. Unfortunately, The Culling defaults to the slow-paced synthscapes that dogged the first act, although there’s some lovely lead tucked away amidst the gleaming samplers, while the picked guitars of Springtime are all the better for being largely free from the everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach found elsewhere.

A more coherent set than Act One, Act Two sees some cracking pieces emerge. While the central portion of the act can get bogged down by Billy’s over reliance on synth, tracks like Beguiled, Moss and Springtime rekindle the fire, paving the way for the third and final act.

Act 3

The third act of Atum is both its best and its longest, clocking in at fifty-three minutes. It is certainly the most varied of the three discs and it opens with the lovely Sojourner, a slow-paced track that strips away some of the layers, leaving Billy’s voice floating on a gentle bed of synths, rather than wreathed in electronic armour. It’s a surprisingly sensitive moment and it’s all the better for it. Next up is a heavier number, and the closest Billy has come yet to emulating Queen. With multi-part guitars and references to Zero, That Which Animates The Spirit is a lively, expansive number built around a sweet riff and offering the band a chance to flex their muscles. It’s followed by the more reflective The Canary Trainer which, as with Sojourner, just feels less packed than similar outings in Acts 1 and 2, cleaving closer to, say, 1979’s sweet groove than anything from the more densely-packed Machina. The synths remain front and centre on the lovely Pacer, which has a latter-day Ulver vibe in its descending chords and subtle percussive elements. A brief digression for the short, sharpIn Lieu Of Failure sees the guitars busting right out of their cage, before the haunting Cenotaph reminds us just how good Billy can be when he allows himself the luxury of a simple ballad.

With the disc progressing rapidly, the palm-muted chug of Harmageddon is another track that shakes off the shackles of the synths to simply rock out and, if Fireflies is a more cinematic trip, then it works all the better for following a more abrasive piece. With the arrangement both subtle and assured, the vocals swoon and drift across ambient percussion, and it proves to be a truly lovely piece of music.

With the end of the story fast approaching, the arpeggiated Intergalactic once again turns to the likes of Muse and, at a further remove, Philip Glass, for inspiration. Expansive and epic in length, as befitting its name, Intergalactic goes through a variety of permutations before landing on a conclusion that sees Jimmy Chamberlin given free reign to run the gauntlet of his kit, reminding us once again just what phenomenal drummer he truly is. In contrast, the relatively slight Spellbinding harks back to the earliest years of the Pumpkins, with Billy and his band indulging a quirky alt-pop number, complete with hook-laden chorus and wide-eyed naivety. Finally, this most epic of albums concludes with Of Wings, which takes in elements of Americana as Billy brings the curtain down on a remarkable endeavour.

Atum

Who but the Smashing Pumpkins, in this era of streaming and instant gratification, would dare to release a three-disc rock opera? It is a truly remarkable endeavour and, at its best, it justifies its billing as a sequel to Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. It is not, however, without its flaws and, in many ways, each disc seems to build upon the last, as if the band were still finding their feet at the outset, only really gelling on the impressive third act. A significant part of the problem is the production, with Billy overegging the synths and allowing certain numbers to expand beyond their range, although his touch becomes more assured as the set progresses.

A worthy effort then, albeit in need of tighter editing, Atum does not reach the giddy heights of Mellon Collie but, to its infinite credit, it does not attempt to emulate it either. As a result, the album stands on its own merits, offering a number of absolutely fantastic songs that stand comfortably next to the best of the band’s output. It’s not always an easy ride, but it is one that rewards those willing to undertake it and there’s a strong argument that Atum is the best of the post-Mellon Collie albums to date. 8/10