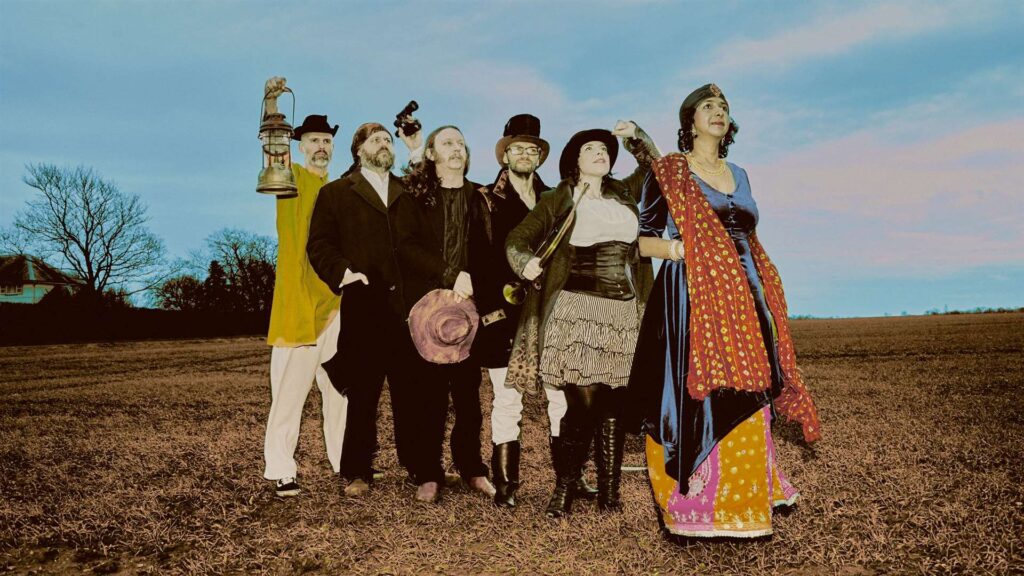

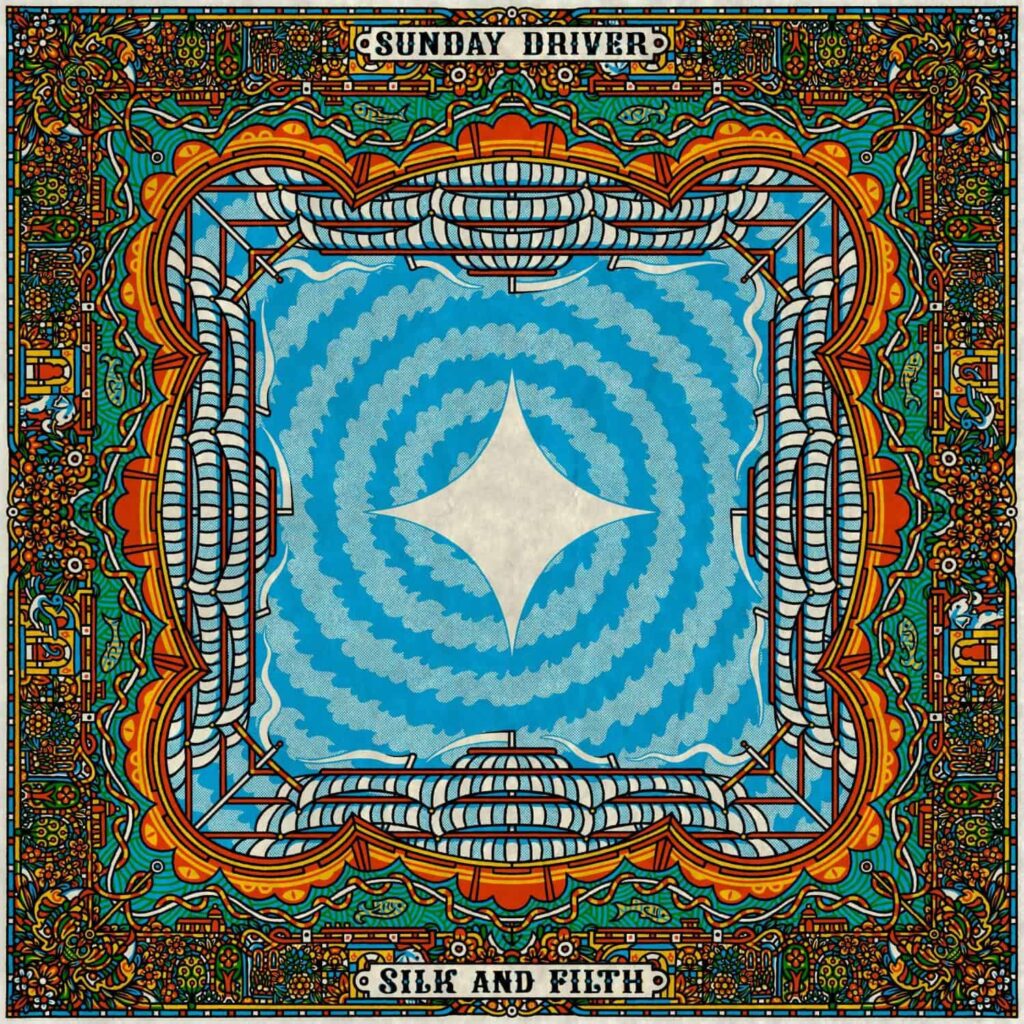

It’s a bright Sunday morning and, adding to my good humour, the second day of a long weekend, with Monday being the May bank holiday. On the stereo, the stunning-verging-on-the-miraculous Silk and Filth from Sunday Driver is drifting somewhere between the speakers (it never seems to emanate directly from them), filling the room with richly textured ambience as I work my way through an epic-length interview with Joel and Mel from the band.

The album, which was released in March via the excellent Trapped Animal Records, is a remarkable achievement that blends a range of sounds and genres into a beguiling whole that seems to absorb the listener for its entire runtime. As might be expected, the musicians behind the album are bursting with stories and love for the project, with Mel proving particularly engaging – his enthusiasm for what they’ve achieved incredibly infectious. It makes for an in-depth interview so, grab a cuppa, fling the record on, and learn more about how the majestic Silk and Filth came together.

You put up a piece on the bad’s website about Devils and how the basis of the band was with Chandy, back in 1999 / 2000, during an expedition to the Antarctic. Could you elaborate on that a bit and talk about how Sunday Driver initially came together.

Joel: A terrible, terrible accident! [Laughs] So, I’m a bit younger than Chandy and she was off doing a PhD – well, she’d done her PhD, hadn’t she, Mel?

Mel: Yeah.

Joel: So, she was off in the Antarctic, and she started writing songs while she was there. She’d started a little bit, and her dad had taken her to a recording studio in, like, 1997 I think – I was still at school at that point! That was around the time I met Mel, and Chandy had recorded some cover songs and a couple of originals. One of the original songs she recorded in India in 1997 was an alternative structure of a song called Black Spider,which is kind of one of our “fan favourites”. We still argue over whether or not to play it in the set. In fact, we had an argument whether to play it or not at the launch party because people actually know the song and like it, and we’ve had it in the set for a long time.

Joel: So, anyway, when she came back from the expedition, she’d written this song called Trip. It was quite heavy, in a way; in a folk way.

Mel: It was intense.

Joel: Intense, yeah, good word. So, she put an ad up – she was looking for a different guitar player to the guy she’d had before – before she went away, he’d moved away or something. And, I had exploded an indie band I was in and I was looking for – I’d basically studied a little bit of finger picking and folk and flamenco playing to get into music college, which is where I met Mel; and I’d never gotten the chance to really implement it in a band or a songwriting situation, because I’d always played in indie bands or heavier bands. So, I replied to this ad, which was on a music board in a music shop in Cambridge – as you did before the internet – and she sent me a tape. My dad said “bloody hell, she’s got an amazing voice! What do you need?” And he went and rented me some microphones, and I overlaid a number of finger picking pieces on a four-track recorded, one of which we ended up making a song out of. I sent it back to her, met her and, around that time I moved out of home and started flat sharing with Mel. Mel played bass and sang, so I roped him in to play bass, and that was, what, 2000?

Mel: yeah

Joel: Cherise joined a couple of years later. Kat joined around that time as well. She was similar…

Mel: She was doing her PhD… In fact, that’s where the name of the band came from because she was doing a PhD in molecular biology. Yeah, we feel dumb a lot of the time around those guys [laughs]. Specifically, there was a gene in fruit flies called the “Sunday Driver” gene, which she happened to be researching at the time.

Joel: I remember, they wanted to call the band Incensed, and we kept saying no, it was halfway to being called incest – we’re not doing that [laughs].

Mel: Yeah, and Sunday Driver kind of stuck, and it ended up being incredibly appropriate because it takes forever for us to get anything done!

Joel: But, to go back to your question about Devils, there was a whole load of stuff with the band, and we went through many iterations. We discovered Indian music via Chandy, and I discovered the Sitar and all sorts. But really, the point is that that trip was so consequential to her entire being and her passion and how she felt while she was out there. It’s just never left her, and it’s stayed in the songs for ever, and she’ll still have elements of that trip, I think, in future songs. So, Devils… She wrote Devils when she was pregnant, or when we were thinking of having… because we went on to get married, me and Chandy. Anyway, the baby was basically in the mix – the idea of having a baby and that.

Joel: So, a lot of the lyrics are a combination of the trip, impending motherhood, and climate change. And that was kind of the intersection. You often knit stuff together once you’ve written a song, when you sit down and try to figure out how to explain it to someone who hasn’t written a song or who, at least, hasn’t written this song – like, what do we want to talk about. And that was kind of where we ended up.

One of the biggest challenges, and it’s something I’ve felt, is that since the internet emerged as a force, there were all these ideas that it was going to democratise music and give people a wider appreciation of music – but it feels like it’s pushed people more into silos, because it’s almost too big for people to grasp what’s out there, so they end up travelling down very narrow lines as a result. So, the impact of that is not just about the difficulty of getting music out there but getting on bills when you’re neither one thing nor the other.

Joel: Yeah, it’s a good question. I often get in my own head a lot about it, actually, and I think that, if it wasn’t my band, I would know what to do with this band. But, because it is my band, I think about it way too much. Because the truth is that we can sit… you can flip what you just said, and we can get away with playing with a heavy, heavy band. We’ll happily support Tool, if they want us – we’ll go and do that [laughs]. We’d probably sound terrible.

Mel: Their support acts always sound terrible, I think that’s intentional!

Joel: It is definitely challenging, and the way I’ve got around it, and the way I’ve got around the whole thing, is I’ve formed a record label so I can do what I want! Before the record label, I just used to put on gigs and book people I wanted. We’ve done really well. We get on really well with Midnight Mango – a booking agency based in Devon – and they’ve got an eclectic roster. We met them because our guitarist saw Raghu Dixit who sings Bollywood-style… very upbeat fusion music. And he was touring and Cherise got in touch. I’m not entirely sure how it worked, but a lot of the time, people will be coming to Cambridge and they’re like “what band isn’t just an indie band?” And we’re like one of the few. Especially back in 2000, we were like one of the few multicultural bands. So, a lot of things came to us. Arts Council funding found us, which wouldn’t happen now. So, I look out for supports like, you know, we just did a couple of shows with Mad Dog McRea – they’re sort of gypsy…

Mel: Sort of folk country kind of thing.

Joel: Yeah, it’s a small pool, but when you find the right people, they really get it, which is what I find.

Mel: Back in the day, we got quite a few gigs playing at Mellors. But the council funding dropped out of the bottom, more or less in 2008 onwards, and it gradually just dried up. They don’t have the budget anymore, if they exist at all. It’s happened to music festivals more recently as well.

Joel: We used to do a lot of acoustic stuff as well. Before we added drums in, we used to jump on folk bills, very early on. The folk club in Cambridge was a like a gateway into that festival.

Mel: Some of the stuff based in London – I’ll never forget the River Bar. Getting an orchestral harp down a spiral staircase, like two stories [laughs]. We don’t tend to bring the harp to gigs anymore for obvious reasons!

It’s interesting that you mentioned Tool, because listening to the album, there’s like an implied heaviness, which is really interesting. There’s very little that’s overt, but you get the sense that it could explode if it wanted to, and there’s an intensity to it that sits very well with heavier music without being intrinsically heavy.

Mel: Well, I think Joel and I independently came to a bit of an obsession with the concept of heavy without being “metal”. It’s something I’ve talked about a lot, it was Scuz actually (Scuz was the guy who played the Mandolin, and he lived, at the time, with the other producer, so he was in the house the whole time). So, we were playing GTA a lot and we had a lot of chats about that and discussing what are the heaviest songs. And he’s a massive metalhead. I mean, I like metal, but I wouldn’t describe myself as a metalhead. But we were picking things like Beethoven and the Beatles – She’s So Heavy was one of the ones that came up. There’s a Wu Tang Clan track about slavery, which is just the heaviest thing you’ve ever heard. And I know, Joel, you had that conversation with someone recently, as well.

Joel: Yeah, there was a Susheela Raman track, Daga Daga which just has the heaviest middle 8, and I remember saying to someone who was working with them at the time, “this is so heavy!” And they looked at me, like, “what?” I don’t think they got it.

Mel: Yeah, no palm muting…

Joel: It’s the Tabla, the percussive sounds, and the brutality of the delivery. Climbing Up the Walls was always a good one for that.

Mel: Oh yeah.

Joel: That was what got me thinking about it – it was an interview with Chino, years ago. They asked him what the heaviest track he’d heard that year was and he said Climbing Up the Walls by Radiohead. This is way back, when they did Around the Fur. And I then understood – you could see the influence of Radiohead between Around the Fur and White Pony. That… they’re heavy, but they’re not heavy like Sepultura heavy. But in some places, it’s darker – that kind of heaviness. I think Mel has got very good at stopping the fact that I’m a massive drop D grunge boy. So, we have to channel that.

Mel: Cherise has said to me on occasion “no, sounds too much like Tool” [laughs]. Yeah, alright, we’ll back off. Since the album, actually, the only tune that has any of that influence in it is We Don’t Belong, but I’ve more recently been drawn into playing in a reggae band (when I say reggae, it’s more dub ragga) with these guys who’ve been doing it for years, and that stuff is heavy. Like crazy heavy, some of it – as heavy as any metal I’ve ever heard. But yeah, you can kind of come to heaviness from different angles, I think.

[At this point Joel has to head off leaving me to geek out with Mel on the production front.]

Mel: We can start badmouthing Joel as much as possible now! [Laughs] Fire away

A while ago, I was doing an interview with Steve Savale of Asian Dub Foundation, and he’s a really interesting guy because he knows a lot about music and musical theory; and one of the things that he mentioned was how Western music rarely incorporates drone well – he actually referenced the Velvet Underground as being a rare example of drone captured effectively – and so I wanted to ask about Sunday Driver and basically achieving an effective balance in the multicultural influences within.

Yeah, it’s actually interesting that you mentioned Velvet Underground because I was obsessed with Venus in Furs for years. And, for years and years, I listened to that tune more than any other. I never actually made the connection but that maybe inspired my love of drone. It’s like an ostrich guitar (where all the strings are tuned to a single note), the violin that John Cale’s playing. But yeah, in terms of what we play, we first started incorporating Indian ideas as a result of Chandy starting to explore that part of her heritage, because there wasn’t really anything discernibly Indian inflected in what she did at first… not noticeably. There obviously would have been influences in there, but you wouldn’t have picked it out. It was more English folk or pop I suppose.

But, yeah, I think the first thing we did was a version of Gayatri Mantra (from In The City Of Dreadful Night)and I remember it because I loved playing it live because (and this dates it) I could literally smoke a cigarette and drink a beer while playing it because I was just playing D all the way through.

I could literally lay my bass down, hit the D, leave it… and that was the beginning of starting to do drone – obviously back when you could smoke in venues (horrible when you think about it these days). Certainly, from my perspective, that’s when we first started using drone.

Then, of course, Joel picked up the sitar, which I think was at least partly an attempt to woo Chandy (or possibly her family) round to the idea of letting their relationship evolve [laughs]. Not that Chandy will be told what to do by anyone.

Anyway, so, as soon as you’ve got sitar, you have drone. It inherently creates drone, with the sympathetic strings, and you’re only fretting one string, so all the others are playing drones.

Around the same time, even before that, we incorporated the drone box (or what we call a drone box) into our sound. They’re traditionally called automatic Tanpura which, amongst purists, are somewhat frowned upon [laughs]. But, when you’re talking about paying a tanpura player, you’re talking about paying someone to sit there and play four notes, leave a gap, play four notes, leave a gap, potentially for hours on end. I love it conceptually, and I have enormous respect for anyone who can actually pull that off because of the necessary patience and the zen-like concentration.

At Joel and Chandy’s wedding, actually, in Bangalore, they had a guy in a band that played, and he was doing 8-hours a day with the odd 15-minute break, and that’s all he did, all day long! And I swear to God, he never missed a beat. To me, that’s incredible – it’s the ultimate distillation of the bass player’s job – underpin everything else and provide the basis that everyone works on.

So, we kind of incorporated those things. We messed around with a harmonium, and then we come to the drone – Malice Scourge is the obvious one. I mean there are drones throughout most of the tunes, but Malice Scourge is this monster drone, and that actually was built around a broken auto-tanpura. So, that kind of rhythm that it plays, that was the drone box basically gone wrong. We had no idea what happened. At some point, something in it broke and something in it started sounding slightly more… It originally uses samples, so it started out sounding like a tanpura, but it ended up sounding more like a synth, so we built the whole tune around that, that’s where it started off.

And yeah, we’ve experimented with – I mean Joe and I (the producer); we became completely obsessed. We were making drones out of everything. To the point where the musicians who came and played for us, we knew all the keys everything was in, we figured out every possible note we could possibly want, and we got them to play that note, hold it, then play the next one. So, we had them there if we wanted to use them for drones – some of which we did, some of which we didn’t.

I also recorded a lot of bells, which we didn’t use any of, which was a bit sad. But then, of course, we also had the tanpura itself and, yeah, actually getting the tanpura working. I don’t know if you’ve seen the photograph of Joe with the Tanpura – normally, you play them vertically, but Joe got it on a keyboard stand and strapped it down and spent ages… um, on the bridge of the tanpura you’ve got these little strings, they create the buzzing sound that make the overtones, and those are essential. And I wonder if that might be the thing that was missing in the Beatles. Because it’s all very nice. Don’t get me wrong, I love a lot of the stuff that they did with the sitar, but it was all very nice – very clean. What they didn’t have was the noise – those harmonics, those overtones that are created by just catching the little string you put underneath, that causes it to catch on the bridge. And it’s that catch that causes a harmonic, that produces another harmonic, which then produces another harmonic.

And, you know, we were very keen to get that effect in there and combine that with the random harmonics being produced by this weird, broken drone box. Harmonium as well. The harmonium we’ve got was a lovely instrument [laughs]. Now it’s rickety and some of the reeds aren’t quite right but, again, it produces certain things, and we did a lot of… that harmonium was recorded repeatedly with different stops pulled. By changing the different stops, you produce different overtones and different chords, and the combination of all those things together – there’s cello… and, of course! There’s one thing we did that isn’t normally done with a tanpura, we played it with an ebow (a little magnetic device); and the guitars were all played with that as well to create constant drones, so there was no pluck sound at all. I mean, I could go on and on around the number of things that we used, threw into the drone, and experimented with.

We were also very, very conscious of only wanting to use synths when it was absolutely necessary. The same goes for effects. If we can do it by using instruments and spaces, then we will do it. So, a lot of the sounds that you hear are more than one instrument playing the same part to achieve the same effect that we’re after – especially the fundamentals (the low subs, basically), which you can’t hear in the music because it’s a sine wave. It’s just there to give it that warmth underneath. That’s one of the very few places where we’ll use synths at all. It’s certainly not based on any dislike of electronic music or electronic instrumentation. Both Joe and I are huge fans of electronica and love nasty synths and dub step and things, but it was part of the concept – to keep it sounding authentic. Joe wants things to sound like they sound. So, 90% of what you hear in that drone is actual real instruments, and then a little bit of trickery in there.

Anyway, as you can tell, I could talk all day about this!

For me, one of the most exciting things about recording and, I guess, you not using synths cuts to the heart of this – is trying to recreate the sounds in your head and doing it in ways that are not necessarily conventional, because you end up with so many cool, happy accidents – especially working with something broken.

I haven’t talked to you about the Franken-clarinet yet, but we’ll get to that, I think!

Franken-clarinet? But yeah, there’s something so exciting about that spontaneity, and you do end up with stuff that’s sometimes, maybe, even better than you’d hoped…

Absolutely, that’s something I tell my students – certainly the more capable ones – it’s lovely to draw on a blank sheet of paper with all the different colours you want, but sometimes it’s really good to be forced into choices, so you’ve got to figure out how to make something work. Yeah, Joe’s house is… he’s one of those guys who’s… I mean he’s got seven cars, all of which are in some state of disrepair. The exhausts are fixed with beer cans, you know – nothing is ever fully working in Joe’s place.

The mixing desk is a 1970’s analogue desk from a studio in Manchester, I think. I don’t know where they got it from. I believe Eric Clapton recorded on it back in the 70s, apparently. But it’s a proper, old school, massive console that he bought – totally fucked – I mean it was completely broken. So, he bought himself lots of components from the Russian government or something. They’re all shielded against EMP – we used to joke that it’s the only mixing desk that could survive a nuclear attack! But they’re really high-quality components as well, and Joe’s this kind of tech genius.

But, as a result of the fact that this unit was kind of Jerry built, it set on fire at least twice while we were recording! So, we had to pause on a couple of occasions while he put it out, chucked the part away and found another channel to go through. This was the process. We were doing it in his house – we were using every room in his house – and that’s where the clarinet comes in. It was the most difficult part, getting the sound of the clarinet. They’re a horrid instrument to be honest. Don’t get me wrong, a brilliant clarinet, played by a brilliant clarinet player, with the right piece of music, when you create enough space in the rest of the music for it… but it just bleeds into everything. They’re a nightmare of a sound to deal with. So, Kat’s clarinet sounds lovely live but try to record it and it was just…

So, it ended up… actually, I don’t know how many clarinets we took to eventually build the Franken-clarinet. Even then, we tried every room in the house. Kitchen, bathroom… you name it, we tried it everywhere. All the different mics – and Joe has stupid numbers of mics. He’s the essential collector. And we ended up recording it – Joe also works in a school – in the school hall. I asked him specifically about what he used, and he used a 1938 ribbon mic [laughs]. It’s completely fucked at high volumes – it would not work, it would completely distort and overdrive at high volumes, but at very low volume, it sounds beautiful. So, he placed that mic at the right place and then he had these hand made little cigar-shaped mics – I don’t know, there’s some guy who makes these mics – and through the combination of those mics and that space, we managed to get a sound that, well, Joe was prepared to sign off. By that point, I’d been saying for a long time “it’s fine, it sounds OK”. But Joe is nothing if not a perfectionist, and it’s a shame he couldn’t be here tonight, because a lot of why the album sounds as amazing as it does is me saying “yeah, yeah – that’s fine” and Joe saying “no!” [Laughs]

All credit to him, because it sounds amazing. So, that DIY thing – the bodge together using what you have and the various instruments we begged and borrowed off people.

It’s hard enough to coral a band, trying to get people out of their lives and into one place is really challenging.

Yeah, and the day jobs in Sunday Driver complicate that considerably. I don’t know if you’re aware of what Chandy does. She was, for a while, the acting director for the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. It’s highfalutin to the point where, when she was passed over for the job permanently, Sir Robert Winston stood up in the House of Lords and made a speech decrying the fact that she wasn’t picked. She’s now, and I’ll almost certainly butcher this, but something like the Chief Executive of the International Antarctic Research Council. Essentially the body that coordinates all of the research in Antarctica, plus dealing with the American and Chinese governments. You can imagine! How she finds the time to do anything else is a miracle. And Kat, as well, she runs her own business in communication, but she always has a million things on the go. So, just between those two it’s difficult to find time when we’re free. But, you know, we manage it. We’ve done a lot over the years in small groups.

I spent a lot of time just visiting Chandy and Joel with an iPad during the actual writing of the albums, just getting them to give me whatever was going through their heads at the time. In fact, the last track on the album, The Death of John Company, Joel isn’t (and he’ll totally forgive me) the world’s greatest pianist – nor am I, I’m terrible – but this was just recording him on his piano and he was like “oh yeah, I’ve done this thing”. So, I recorded it, and we realised that when we got someone else to try and record it, they played it far too well. And we kept telling him to play it worse, and Joel eventually had to say, “just imagine it’s the worst day in your life,” and that’s when it all came together.

So, yeah, the songs were written by going to those guys in particular and getting whatever they were doing at the time. So, there was a lot of legwork for me, and then bringing it to other members of the band and asking them what we could do with it. The little iPad I used (I don’t think I even know where it is anymore and I doubt it would work), but that was where the album was built in the first place, with me just going to different people in the band. And then, we got into the practice room and got all of us together so we could look at what we had and figure out what to do with it. And then we’d argue, quite vociferously. [Laughs]

But, that creative tension is necessary because, by achieving something that we could agree sounded good, we could be pretty sure that it did sound good.

And you can really hear, on Devils for example, Chandy wrote that song, and I wrote the cycling bassline, which I’m no longer allowed to play live – everyone else plays it while I play the root notes!

I hardly play any of my basslines anymore, someone else has stolen them. But, yeah, there were other details added on there, some of which made it literally direct from the actual iPad onto the album. There’s a piano, a distorted piano line, kind of high pitched, which we tried re-recording, and it sounded rubbish. That was recorded with an iPad sat on top of Joel’s piano when we first created the tune, with the iPad distortion setting. And that is literally it.

So, yeah, it was very much a case of going round and getting everyone’s bits, bringing it all together, and then spending however long it took to actually thrash it out. And then some things changed in the studio as well. Not huge numbers, but there were bits that were constructed wholesale in the studio out of bits that people had recorded when we realised “oh, right, it needs to do that”.

And the last few weeks, now we’re actually playing some of those songs, we’re having to work out what we actually did. A couple of the basslines are physically impossible to play. There’s just no way. Yeah, Joe’s also a bass player and, you know, I wasn’t precious about it. If you’ve got a good bassline, play it.

But, the other musicians, the main thing I’ll say about the other musicians is [awed whisper] oh my god! Just, off the scale. We did our previous EP, which I think was 2014 we did Flo, we used it as a bit of proof of concept. Firstly, recording with Joe, because he’d been our live engineer for years and years, but we hadn’t recorded with him before, and we knew how jerry-built all of his stuff is. So, we wanted to see how that would work. And, of course, it worked great.

We also got… that was the first time we worked with Kuljit, who is a legend. But, you know, the thing is you work with someone who’s got that kind of reputation and who’s done that kind of work, the question is always going to be how well they slot in. Because we’re not asking him to be the star here. I would happily make an album with him as the star, because he’s incredible. But we’re asking him to fit around us and you never know exactly how someone is going to adapt to that. But, after we recorded Flo, we were clear we had to get him, no matter how much it cost, because he’s off the scale.

The other one is Geoff, the cellist who, again, is a friend of Joe. I don’t know how they actually knew Kuljit, but Geoff’s an old friend of Joe from university. He’s actually a professional singer and he does choral kind of stuff, like small group choral things. He’s in Germany now, I think, doing that for a living. We knew he used to play the cello and had a really nice cello, so we asked him if he’d dust it off for us and he just did an incredible job. So, those guys we kind of already had in the bag, we knew we could work with them.

Owen, we’d known for years and when we realised we needed a piano… well, my little brother is a pianist as well, so we talked about getting him; but Owen, he’s an improviser – and the end of Bank Job in particular, we knew we wanted massive improvisation. We were going to let everyone just do their thing and then figure it out afterwards. I mean, I’m not sure he did more than two takes on the whole thing. He was great. And we realised recently that we forgot to put in the liner notes that he also played the banjo – ooops! The banjo – I don’t think a banjo ever appears without a sitar playing at the same time. We tied the two things up everywhere.

Scuz played the mandolin parts for us – Joe had played the Mandolin part on We Don’t Belong, but he’d be the first to say that he’s not the mandolin player that Scuz is. He actually played our launch a couple of weeks ago, and we just got him to play guitar on everything that he wasn’t playing mandolin on, and he made everything sound better. He’s just amazing. And he’s playing with us again. He’s one of those guys that I can just ask him a question about music and then sit for an hour listening to him talk, because he just knows it all. He knows so much. He taught me all about different ways of tuning intonations. All the stuff about harmonics – this is while I’m playing GTA, right? So, he was an obvious choice to get in to do that.

Then, probably the most interesting one for me, partly because we have no idea where she’s gone, is Alex – who did backing vocals.

You won’t know listening to it, but if you hear Chandy singing on this or the previous album, you’re also hearing Alex. Everything that Chandy sang, Alex also sang. And the reason we got Alex to do that is that she’s just an incredible mimic. She can just copy exactly how Chandy was singing but, where Chandy has a very trained voice, Alex has a very untrained, breathy voice, and it just fills out the frequencies beautifully. You’ll hear it in places on Les Amoureuses – she’s the interlock vocal. But what you’re not hearing is everywhere, literally everywhere, Chandy sings, so is Alex.

And what we said earlier about trying to avoid using effects where we could, this was a way of avoiding layering up various reverbs and double tracking. We didn’t want Chandy double tracking; we wanted her voice to be her voice. There are some places where she does harmonies with herself, but otherwise it’s single-track vocals. But yeah, Alex – Joe and I were at a gig of a band that I used to play for before they moved on, and she’d gone to Brighton and come back and we’d gone to see this gig and, after the second song, Joe and I were both shouting across the room to each other “the backing singer, it’s her, it’s her!”

And we didn’t even talk to her that day, we had to track her down because she’d left that band. So, we found her, got her to come up and sing, spent two days with her learning just how to be Chandy, copying everything that she did to a ‘T’ and getting her to record it all, plus a number of harmonies. She was just such a worker. She hadn’t sung in a band in two or three years, she had no ambition to be a musician at all. It was years since we’d seen her and tracked her down.

But, since we finished the album, she’s gone. We can’t find her. I don’t know if she’s even ever heard it. She went travelling and no one seems to know where she’s gone. So, yeah, hopefully one day she’ll show back up and hopefully in time for the next album.

In terms of album sequencing, one of the things I’ve enjoyed is the shift away from people arranging albums according to the maximum length that a CD could hold, whereas it feels like a lot of artists and you guys in particular were thinking in vinyl terms.

We very much were! The demo process incorporated something like 80 different pieces of music in various different amounts. Maybe 30 – 35 tunes that Chandy just gave us, and we picked a few that we worked on – Devils, Keepsakes from the previous album; and then bits and pieces that other people had brought along. And some of them ended up as one tune, and most of them just ended up not being used. We got it down to the fifteen actual songs that we had prior to recording – the three instrumentals all came slightly later.

I should explain. The two albums – Sun God and Silk and Filth was one project – it was never conceived as being two albums in the first place. We just imagined that we’d whittle the numbers down. And we weren’t thinking vinyl at the time – this was before the days that Joel had started doing quite nicely selling a bunch of vinyl. So, we were imagining a CD / digital release. So, we were thinking maybe 50/60 minutes long – I don’t think we were thinking any longer than that. But, as it went on, and we added in the instrumentals, we got to a point where we realised we really liked everything and didn’t really want to leave any aside.

And, of course, the concept of the vinyl emerged. We talked about double vinyl, but double vinyl is just so hard to sell. In terms of making our money back on it, it’s prohibitive for a band like us. So, we sort of decided it would have to be two albums. So, with that, I can’t tell you how many folders full of word documents I have, with different song listings with the numbers of minutes next to them, trying to figure out how to fit these 18 tunes onto four sides of 21 minutes. I absolutely drove myself insane figuring it out!

It’d be fine with three-minute pop songs, but seven-and-a-half / eight minutes? So, you have to physically fit them on to each side, and you have to make it flow and tell a story because there is a story being told here. And it’s something I always kept coming back to – each of the instruments that features very prominently is a different character in the story.

So, Chandy’s voice is the star, and every other instrument is a character that appears. And who knows, some characters appear for one scene and then you never see them again, but most will disappear and then come back playing different parts in different scenes. So, we had to try to make it so that, across the two albums, each one made sense as a story. The level of obsession I went into with that was absurd, frankly, my wife would say, “you’re listening to that again?” To the point that two years after, I just couldn’t listen to it.

I’m now back to listening to it all the time again because we’ve just released it. So, I was utterly obsessed with it, to the point where, in fact, both Joe and I… by the time we came to sign off on the final mixes we couldn’t hear it anymore. It was really difficult for us to hear it because we’d just heard it so many times. And you’ll see on the sleeve it lists special thanks – and half of the people in those thanks were involved in some way, they lived with Joe, or they helped us out. But actually, the majority of those names are people, including some obvious internet handles (which were some guys I knew from an online mafia community) – just anyone I could get who I trusted to have taste and a good ear, we gave it to them and said, “just tell us the problems. Tell us the things that we can’t hear!” And, yeah, that was enormously important to finish it off. We just ruined ourselves.

But yeah, I think that, both Sun God and Silk and Filth work really well. Curiously enough, it worked out that the majority of the songs on Silk and Filth were written after the ones on Sun God, although it wasn’t intended that way. So, it does represent our later work. I think you can probably hear that – there’s an evolution from that. But conceptually…

I don’t know how much it says in our press release in terms of the names of the songs? But the concept of the whole thing… I made Chandy watch The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, Fistful of Dollars, and For A few Dollars More. I didn’t really care about her watching it, but more I wanted her to listen to it before we started the whole process – just mainline Morricone. Absorb it and so, there was that concept.

And Chandy is insanely well read, and there’s a million different threads of thought in what she’s doing and thinking about it. So, there’s a lot of historical elements in there. And, in particular, the one running theme that goes through all of our albums (except for Flo, which is purely Indian in nature), is British Indian colonialism. You know, because in the end it’s why we as a band exist. Chandy’s family came here, I think, via Uganda a generation or two ago. But fundamentally it’s that connection, and we mine that a lot.

So, it’s the story of Silk and Filth, and the choice of songs to go on the album, there’s a big nautical theme there. You can see it in the cover, obviously, with the sails. And Malice Scourge was the name of a ship. In fact, the same ship changed its name to Red Dragon. It was Malice Scourge when it was robbing the Spanish in the Caribbean. It was owned by a privateer and then subsequently bought by the East India company and sent round… in fact, I understand that the first known place where Hamlet was performed outside of Britain was on the deck of the Red Dragon. I mean, imagine what these tough sailors… one of them playing Ophelia… [laughs]

So, we were doing a lot of reading about this stuff looking for ideas and concepts. And Chandy’s lyrics weave in and out of all of that stuff. Silk And Filth in particular. So, it’s historical, but it’s also about now, and the concept she has about the interrelation of the beautiful things that commerce brings us – the Silk Road famously being that big, first trans-Asian connection; and she was thinking about the beautiful Saris she loves to wear on stage, and then how they come from places of grinding poverty and often horrible exploitation. And all the terrible, terrible things that have been done to make our world the way it is. So, there is inherent in that, this tension, because the outcome is… I mean, the most beautiful outcome is Leila, Joel and Chandy’s daughter, who without that history, she wouldn’t exist. And she’s an incredible musician as well. She’s a serious pianist for a nine/ten-year-old she’s going to be something. I mean with those parents it’s not surprising I suppose. But yeah, also all the music we make and all the other beautiful fruits…

But you can’t look away from the nastiness – the horror and the brutality that not only did happen but still is happening. So, I think in the song The Death of John Company – John Company was the nickname for the East India Company. So, the reason that it’s the last tune is that it’s the brutal coda – this is still happening, it’s still there. Joe and I imagined that the body just sank down into the water. So, you begin Malice Scourge in the belly of the beast, inside the belly of the ship – waking up inside this wooden thing, travelling across lands that you’d never imagined.

So, yeah, the idea was to try and tell the story through the album that kind of encapsulates those ideas. And I don’t want to spell out for anyone exactly what they should think. This is just what I got from it. If you asked Chandy, you’d get a different idea about what the songs mean. There’s Panda Ballet – you’ve got the beautiful harp and the nasty cello, so you can conceptualise it in various ways. But, yeah, to try to come up with a conceptual narrative through the album, but at the same time also thinking aurally and dynamically, is a challenge. You can’t just go loud one / quiet one / loud one / quiet one. And there are plenty of albums that do do that, but there was a lot of time spent on it. And then it’s also about the beginning and ends of tunes and what sounds right.

For the future, I think, yeah, in terms of making an album for vinyl, we have a concept and it’s going to be interesting – but I don’t want to say too much. I may spend even longer trying to organise that one!

My last question – I think it’s really interesting that you were looking to soundtracks for some thematic ideas. Soundtrack composition is really very visual and, when I was listening to your music, it’s very evocative. Do you, as writers, have mental images that help to drive the way the song progresses?

Hmmm. Personally, no. I’m not a particularly visual person. I suspect Chandy would probably say yes, but I don’t know for sure. Also, I should add, I’m… although we all work together on composition, traditionally I’m the one who composes the least out of the band. The others compose and I produce. And we agreed right back in the early days that we would always split the credit. It’s just written by Sunday Driver together to avoid any sense of anyone trying to fight for their own ideas. As it turns out, half the time, we’ve forgotten who had what ideas in the first place – we’ll argue about it later!

But, yeah, my part in it was more about helping to get the arrangements into full compositions. But personally, I don’t particularly have visual images, it’s more words for me. I’m a massive, avid reader. I’m kind of working my way through Moby Dick which is definitely going to feature on the next album. I particularly enjoy the bit where he describes very clearly that Whales are Fish. I’ve been saying that for years, trying to wind up scientists, but I’ve got a background in philosophy, so… For me, it’s much more the literary thing – the idea is telling the story. I wouldn’t particularly have visual images. But definitely a sense of place. Very much so.

I think, at this stage, it’s difficult to underestimate how important it was that the whole band at the time went to Bangalore and then to Carrola when Joe and Chandy got married. That experience together, there, visiting the temples and listening – like I said, there was a band that played for four days, starting in Chandy’s garden when she was being hennaed – and then three days of the wedding.

And no booze as well! A bunch of musicians at a three-day wedding with no booze! [Laughs] So, obviously, we were paying a lot of attention to the music and those guys played basically non-stop for three days. They were incredible. I’ve been known to wax lyrical about the Tanpura player – four notes over and over again for three days! That journey and spending that time together – it brought us closer together as a band. Perhaps not the bit where we had to strip down to our scanties and remove leeches from each other(!) [Laughs]

Who knows, it probably did bring us closer! So, that kind of imagery I’m sure has had an effect in there. So, I can’t give you much more than that on the imagery side.

Thank you so much for the great interview, it’s been such a pleasure chatting about this.

It really was a labour of love and it’s been great to be able to talk about some of the crazy shit we’ve been doing. If you ever get a chance to talk to Joe – not necessarily about this. He’s producing the Baby Seals… I don’t know if you’ve heard them?

Yeah, they were one of my albums of last year – I love them

Well, he did that one, or at least he engineered it. I believe he’s doing another one for them. That’s what I heard last – down the rehearsal room with the grunge band I sing in with Joe – it’s a little Sunday Driver spin off. In fact, can I leave you with an anecdote?

Sure!

This is the kind of band we play in. It’s a spin-off of Sunday Driver. It started when my good friend Clive – who’s also mentioned on the album and he’s depped for Sunday Driver – they were going back to drop him off at his practice room, which is on a farm in Essex. It’s an old refrigeration unit. Anyway, they went back, and he said, “do you want to come in for a jam?” and they had a jam. And they needed a singer, and they knew I’d retired years ago as lead singer. So, they asked me, and I went and joined them. We formed a band, playing a load of grunge / doom kind of stuff. Nasty, sleazy music.

And we went and did a bunch of gigs, including a grunge night down in Croydon at a place that, sadly, no longer exits. It was called Croyattle. And this night we went down, they obviously didn’t hate us, because they invited us back for a second one. It was a year after Chris Cornell’s passing and there was a little table with a picture and a single rose in a vase, with tea lights around it. It was a little shrine before him. And the two bands before us were both doing grunge covers and they were in their 20s, right? We were around when it actually happened. Every third song, it was like “this is for you, Chris”. And there were lots of really gushing things said about Chris Cornell and how much they loved him.

Then, we got up on stage and I had to do it – when we got up on stage, I had to announce the name of the band. So, we got up on stage and I said, “ladies and gentlemen, we’re Glad He’s Dead!” Half the audience laughed and the other half… we spoke to the promoter; he just hadn’t thought about it! It just hadn’t occurred to him that he booked a band called Glad He’s Dead for a tribute night!

And with that, I’ll leave you!