Since 1979, Tommy Emmanuel, one of the very few guitarists to be awarded the status of Certified Guitar Player by Chet Atkins, has released twenty-six studio albums, many of which have achieved high chart positions in his native Australia. His latest release, ‘Accomplice One’ was two years in the making and features contributions from some of the greatest guitar players in the fields of rock, blues and country music. Released via the Players’ Club, a boutique imprint of the mighty Mascot Records, ‘Accomplice One’ is one of those rare records that makes you feel as if you’re in the studio with the assorted musicians. Authenticity, for Tommy, is everything. So, there were no small amount of nerves when we discovered that Tommy had agreed to speak with us about this remarkable offering.

Hey is that Tommy?

Yeah it is, how are you doing mate?

I’m good thank you! Thank you so much for agreeing to speak to me.

You’re welcome, thanks for your time.

It’s a pleasure.

So, to start off with, I wanted to ask you about the Certified Guitar Player moniker. I’ve always believed that qualifications, in whatever field, are very much the start of a journey, rather than an end, so what I wanted to ask, when Chet gave you that title, obviously it was a great recognition of your talent, but in what ways did it spur you on to consider your talent and develop further?

Well, that’s a very good question and you hit the nail right on the head. The moment that I realised that Chet had done that for me in public, in front of everybody, I realised that it was a responsibility. More than anything else… and it was a responsibility to honour the music that had got me to that point. And to honour the people who helped me get there and who showed me the way, including him. And then, also, to hand it on and to inspire the younger generation to do the same kind of thing. I felt it was a way of saying “if I can do it, you can. How dedicated do you want to be? How hard do you want to work? What do you want to achieve? If you want to achieve what I’m doing, then you have to start now, and you’d better be dedicated and disciplined and play for all the right reasons.” That kind of stuff – that was what was going through my head in the first week after I received that award.

It’s been a great journey from that moment onwards because a lot of people couldn’t believe that a guy like me could achieve something like that. It’s really fired me up, it’s made me feel inspired and made me feel very conscious of my calling and my place in the world. That I should show up and do my best and show younger people that, if I can do it, they can.

Perhaps one of the thing that comes with this award is that, because it’s bestowed on so few people, it’s being able to attain that balance between technicality that comes from practice and earning your craft but then also the maturity and passion that allows you to stand back from the technicality and imbue your playing with emotion and that’s something that, perhaps, players can only learn over time.

Exactly. When people only talk about technique, I always say “technique should be invisible.” If it’s good, it should be invisible. You’ll only feel the music and feel the playing, you won’t be gasping at someone’s technique, you’ll be gasping at how good the music is. That’s the way it should be. That’s what I think. It’s like… you watch Tom Hanks on screen, you’re not watching a guy act, you’re watching a guy being the character and doing the things that character would do. You’re watching a person actually do it and you believe it. It’s not Tom Hanks acting – you’ll never catch him acting. His technique is flawless.

The reason I stared down this line is that, when I first listened to ‘Accomplice’ it’s a remarkable example of all the studio wizardry stripped away so what you have left is the core of the blues and country represented in this very naked way and that’s very brave, I think.

Thank you for saying that because my vision for this project is exactly what came out and with every artist I wanted them to bring something a little different and I wanted everybody to be playing and singing live in the studio. No one mailed in their part and that’s why it sounds the way it does. It’s all real and we could go out and perform it exactly like that. People like Ricky Skaggs and Rodney Crowell and you could bring a song to them or they could bring a song to you and you just sit down and play and sing it and it’s right, you know. You don’t have to be labouring over it, it just flows, it’s all natural and those guys work at that level and they’re the kind of people that I want to be working with.

There are some really lovely moments on the record – some really spontaneous, off-the-cuff moments.

Yeah, that’s right – I say “yeah, it sounds good, but it’ll be better when you get your guitar in tune!” and J.D. had no idea that I was going to say any of that stuff – we just went into it on that take and we just left it on there.

It seems to me that there has been a move in the blues community where there’s a deliberate reaction against all the glossy, over-produced music and I think it’s really important to keep that passion and authenticity, particularly with the blues, but in all forms of music.

Exactly, you don’t want to try and shine and polish it and make it perfect because nobody’s shiny and perfect, you know, and recording should be capturing a performance, not manufacturing one and that’s how I look at it.

I made a live album two years ago, ‘Live at the Ryman’ and my memories of that night… I didn’t feel that great about my playing, but I knew that I was concentrating to try and play well, and all my focus and energy was on that and giving the audience a good time. So, I walked away from the project thinking it probably wouldn’t be good enough for a live album and then, a month later, I heard it and I said “let’s just put it out like it is. It’s real, it’s honest and actually everything’s in tune, everything’s in time. You have good feeling and you can sense that the audience were with me all the way.”

So, I did nothing to it. I didn’t fix anything up – I just put it out the way it was, and it stands up and that’s what being a musician is all about. Trying to nail it and nail it right. And not have to go back and fix things up.

The history of the blues, perhaps more than any other genre, is one of re-invention where you get up-and-coming players who play their respects to the previous generation but, at the same time, put their own stamp on a cover and ‘Accomplice’ is about doing that. So, what is it you look for in a cover or do you just feel it when you hear it?

Well, you take a classic song like ‘deep river blues’ and when Jason Isbell came in… I’m a big fan of his – I love his writing and his playing, and his singing and I asked him if we should have a go at ‘Deep river blues’ and he said he loved the song. So, I gave him the lyric sheet and he sang it like it was meant to be sung. He was the right guy for the job. He didn’t need to play anything. He just sang, and I played and when we did the take and we were all happy. Then the engineer, he added some upright bass and it was complete. There’s nothing else on there. My acoustic guitar, the bass, Jason and my vocals… and it’s just like a live performance.

A particular highlight was your version of ‘purple haze’ because, from the second you get those chords, it’s instantly recognisable, but at the same time, it’s your own. Stripping away the firepower from Hendrix… that’s a brave move!

[Laughs] Well, thank you. The idea behind that. On the day, Jerry Douglas came over to the studio and I had written a ballad that I wanted him to play the melody and I had to teach it to him. That took a while We got that done and then, kind of as an afterthought, I asked him if he wanted to have a go at ‘Purple Haze’ and he asked me how it went, so I showed him, and he told me not to play anymore, so we just had a go at it. He went into the room, and I went into the booth where I was, put the headphones on so we could hear each other very well and I told him to follow me and then I would follow him, and he just needed to watch me for the nod when he would take over the melody. So, it was one take and it was just him and I looking at each other and giving signals. It was just a jam.

That’s the recognition of any great song when you can strip it down and it’s still a great song. And it sounds great, even totally naked. It’s the mark of a great song-writer.

Exactly. It’s such an iconic song and my wife was on Reddit one time and she did a poll which asked what song people wanted me to arrange and play and, by a long way, the vote was for ‘purple haze’ so, what I did… there’s a video of me playing it on my back porch on YouTube and, the truth is, I wasn’t that fussed to do it but my wife said “look, this has been a very popular thing and a lot of people would love to hear you play it, why don’t you arrange it?” So, I went on YouTube, found the track, listened to it twice, found the song structure, figured out how to play the melody and chords at the same time and then we went out on the back porch, I played it once and she filmed it, we put it up on YouTube and it went crazy form there. And that was it. Form that moment on, I’d always remembered what I came up with, so that’s where it came from.

The flip side is that straight away afterward you have the very emotional and touching ‘Rachael’s lullaby’ – how did that track come together?

That track was written because Rachael loved ‘blackbird’ so, I wrote a song that was like a tribute to ‘Blackbird’ and, if you think about that and listen to the song, you’ll see how Beatles-esque that song is, and I purposefully did that because Rachael loved the Beatles and I always loved that song too. So, I wanted something that had that feeling and I definitely wrote it with that genre of song-writing in mind. There’s no improvisation in Rachael’s Lullaby – I play the melody as if I’m singing it.

That’s an interesting point because I’ve read various interviews where guitarists say that guitar playing, at its best, can mimic the human voice and the range of emotions expressed within it, and that’s what you were trying to do…

Exactly. And I always try to think that way. I remember when I was writing songs thirty years ago and I would ring Chet Atkins and tell him that I had a new song and then ask if he’d want to hear it and he would always say “can you sing it? Can you hum it?” That was what he always said and that was instilled in me right from the beginning. If you’re going to write songs, they have to be sing able, they have to be memorable and able to be listened to a thousand times.

In terms of recording the overall album you said it was live and no one mailed things in – how long did it take to put it all together?

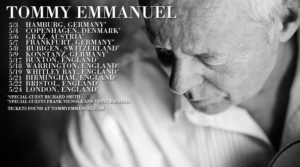

Well, this album was pieced together over a two-year period in between touring and other commitments. I used two different studios in Nashville. I used two different studios in London, where I recorded in London. I had to go to his place which was an incredible studio in Chiswick. Then we went to Rack Studios – Clive Carroll and I – to record ‘keepin’ it real’ together. Then we were in Havana, Cuba, and we recorded ‘Djangology’ with Frank Vignola and Vinny Raniolo – we recorded those down there. The rest was done in Nashville. The track with Rodney Crowell I did out at his house – he lives just outside of Nashville.

So, a real labour of love. When you put it together, how did you work n sequencing the record to make it flow.

It’s one of the parts of the recording and album-making process that I really love. There are several ways that you can do it. You can put the first 20 seconds of the song and then cut that off and then straight away the first 20 seconds of the next song and then you can play it through and see how it unfolds. You have to listen to the whole thing. The other way is to just know the songs well and say “this needs to follow that…” there are even things like looking at what key the track is and making sure you have a different key on the next track, because you don’t want two songs in the same key next to each other. So, even things like that. But, there has to be peaks and valleys in an album and it’s a very interesting part of being a producer and I love it.

It’s one of my favourite things when you do have an album that takes you on a journey and you don’t want to skip a single thing because you know it’s part of the journey and one of the reasons I’m so happy with the vinyl resurgence is it encourages that kind of mentality.

Absolutely – me too. We’ve actually been selling more vinyl than CD in America, there’s a big resurgence right now.

It’s pleasing to see and that funnels into labels like Mascot, probably one of the best labels out there right now, and you have the Players Club with you and, of course, The Koch Marshall trio – how did you come to be on that label specifically?

Well, we sent them the album and they liked it and I wanted to work with them because they’d done such a great job for my friend J.D Simo and he was bragging about them and I said “well great! Finally, a good label!” because it’s really hard to find a good label nowadays, and they’ve really proved to me that their hearts in it.

There’s one song that we haven’t mentioned that I love – ‘dock of the bay’ – such a well-known, well-worn song and yet your version is so evocative of summer and warmth. How did you approach that, so it became your own?

Well, the first thing I did was I changed the chorus. [Sings: sitting on the dock of the bay dum dum dum – just wasting time…] I’ve never heard anyone do it that way before. They always go straight from ‘dock of the bay’ to ‘wasting time’ with no pause. I put that little extra bit in to make it a little different and J.D. did a great job on the vocal on that.

It’s a great version of a track that I have a great deal of affection for anyway.

Well great! Thank you.

So, thank you for your time, it’s been a great pleasure talking to you.

You too, thank you.