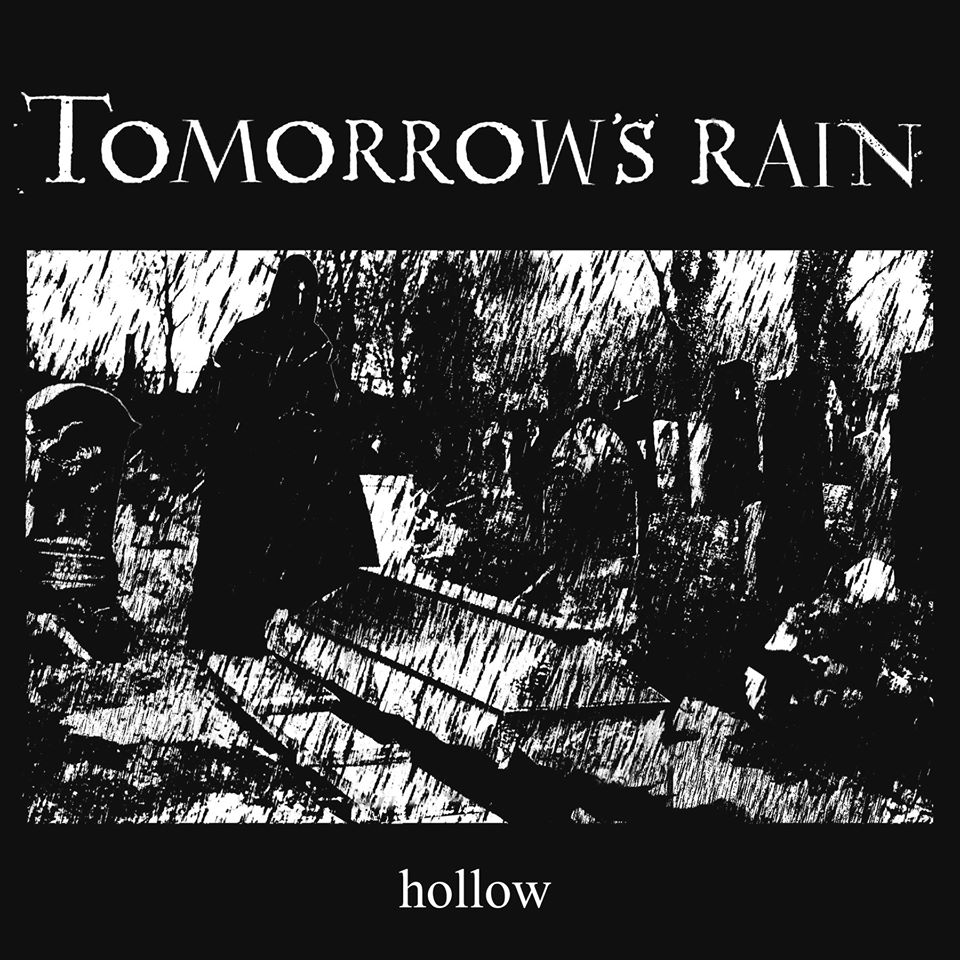

It seems fitting that one of the albums of 2020, a turbulent year by any metric you care to use, was forged in the deeply personal turmoil of its creators. Nevertheless, it is the case that, for all the melancholy that shrouds Hollow, Israeli act Tomorrow’s Rain have crafted a remarkably atmospheric work of art that transcends its influences and emerges as an album that is as haunting as it is memorable. An album that captures the attention with its gorgeous, hand-crafted artwork, Hollow draws from doom, metal, progressive and post-punk in order to chart a unique emotional landscape, and I was delighted to have the opportunity to discuss the band’s troubled history with founding member Yishai Sweartz, who speaks with passion about a project that has taken years to come to fruition.

Hey how’s it going?

Yeah, fine, how are you?

Very well, thank you – it’s great to have a chance to chat to you.

Great, thank you!

As I understand the history of the band, you started in 2002 and then, for various personal reasons, things in your life led to you shelving the project around 2006 before starting up again in 2010, that’s more or less the timeline?

Yes, that’s right.

So, the first question I have is to do with the nature of art and music because, for a lot of people to be in a band is cathartic, but there’s also an element of performance; but for you it seems, it wasn’t really possible to inhabit the lyrics in the way that you wanted when your life was happier?

Well, I’ll tell you two things. The sensation of adrenaline pumping when you are on stage or having people at the show… I’m a promoter here in Israel and have been for thirty years now and I did a lot of metal shows with a lot of bands. So, I have the energy and I am connected to the scene. In the times that we stopped activities with Tomorrow’s Rain and Moonskin, I did (I don’t know) 200 metal shows in Israel with bands that we all know. So, you know, it was not really boosting my ego to go on stage and have 2-300 people saying, “we want more”. It’s not the reason that I’m doing it.

…And I felt that the songs that we had written as Moonskin were written in a very specific point in our lives, from a very deep place in our minds and I felt that, if I go on stage doing these songs, and I’m not feeling them… I’m not feeling them – I’m feeling much healthier; much happier… and it’s the first record – it would be to lie to the crowd. It would be to promote an image that is not true. It would be like going to a day job.

So, I had two opportunities. One is to change the musical idea and write some new songs with the band, and that means sounding, I guess, different. And the other option was to say “OK, enough for me as a musician right now – I will stay on the other side of the glass and I’ll be a promoter, music magazine editor, distributor…” And I did all those things. I had a very big distribution company in Israel doing distribution for all the big metal labels… at the same time, since the beginning of the 90s. So, I said “OK, enough with music for me for a while.”

Then, things changed also inside me. I got divorced, and I took it seriously, and music was my first saviour. I felt that, you know, it’s a good way to embrace the pain. It’s a good way to express the things and then, step by step, I started to feel like we could control the amount of emotional balance between our songs and to create something that we can play and record on a solid, atmosphere.

I’ll tell you what I mean. When we started to write the songs for Moonskin, things were very, very intense in our lives. Me, and Maor … the other co-founder of the band, he’s now a mastering engineer in Los Angeles and we wrote the songs and our lives back then were hellish… it was crazy.

We put everything into the music and every time we played these songs, you know we played with other people in the first line up of the band, and we had some really… let’s say: not really balanced people in the band back then. And when I say “not really balanced”, I mean going to rehearsal in the night with the other members and suddenly our bass player is stopping the car inside the traffic and he said “oh, I need to check, the kid that we just hurt – is he bleeding, or should we call an ambulance for him?” And he stopped the car in the middle of the motorway, with the fucking danger, in order to search for a kid that we never saw and never even met. Totally fake, and the guy is fucking serious. He’s fucking obsessed. Not because of the drugs…

And then, somehow, we got him back to the car, went to the rehearsal, did the rehearsal, and he stopped… ran around the amplifier to search for the blood of the previous band that had played there. I’m fucking dead serious! And you look at the guy and you think “what the hell is this?!” And, you know, I was depressed like for other reasons. Maor, his old band split up and he also wasn’t right back then… but the guys we had at the beginning, every one of them had their own… characteristics – let’s put it like this! So, other than this atmosphere, we wrote the songs that became Trees, or In the Corner of A dead Street – two songs that ended up on the record.

But I couldn’t continue with this. I mean, I could not continue with the line-up. It was too much for me to handle. One of the guys, in the middle of rehearsal, started cutting himself with a guitar string in the lip and his lips were totally bleeding. So he took the towel, put it on the towel and then put it on the amplifier for all to see and it was bleeding like hell. And I was like “what the hell?!” I’m into this band for doing music. I’m into this band to face my demons. But I’m not into this band to be a part of this cuckoo place! What the hell? You know? It was serious. Some of the guys were hospitalised, some of the guys were not really balanced and of course we could not continue with them. Only me of Maor and Raffi were left. So, we replaced band members and band members and band members and some of them were not really that good to play with… let’s call it this way.

So, at some point, I said that I couldn’t continue with this. It was not for me. I was about to get married; I had a job as a promoter, I was doing business as a distributor. I didn’t want to go to rehearsal to see someone cutting their lips with a guitar string and putting a towel full of blood in front of my face. So, we stopped… I stopped, and then the band stopped. We played our final show back then with Epica, in 2006.

…and then after a couple of years, when I got divorced, I said to Raffi: “let’s do it again and find the right people”. And from that point we had a show with Dark Tranquillity and after that we became really serious about it. Finding the right members – no drama queens. Serious people so that we could do it in a way that was good for everybody. Also, I changed. When the songs started to be written as Moonskin in the year 2000 – we’re talking about 20 years ago – 20 years ago I was 25. Right now, I’m 45, so you can imagine how people in change in 20 years. In your 20s, you’re a kid. Right now, I have a teenager in my home! My daughter is going to high school. So, people change, and the perspective changes as well.

I think writing lyrics, at the best of times, is a very personal thing – particularly when the ultimate basis of the lyrics is biographical. It’s quite challenging to get a balance between biography and a more universal experience that will reach an audience. Is that something you ever consciously considered, or is that something that came through the evolution of the music?

Well, I never think about the audience. Not when we write the music, not when we write the lyrics. I never think about what the audience would say or what the people would say. If they’d feel comfortable, if they’d like it or not like it. It’s not on my radar. I try to write, you know… what I feel – cliché as it may sound. But that’s the only thing that I know. If you put too many outside elements into your decisions when you start to write then, again, it’s work! And I don’t want this, I have my work – this needs to be art. That’s the answer.

The other things that interested me from a lyrical perspective is that you released the album in English and Hebrew. Language is such an integral part of personal identity, so I wondered how the approach of writing in two different languages would be, because it’s never just a straight translation if you want to keep the poetry.

We translate the idea; we never translate the sentence by sentence. We translate the idea.

So, is this something that you do on your own, or did anyone help to get the flow and feel?

No. Actually, writing is not a strange thing for me. Before I was a musician and before I had my first band, I released in Israel, a poem book – a book of songs, when I was 16. It was one hundred songs in Hebrew. We’re talking about ’92. You know, writing in Hebrew is very natural. It’s not a problem. Writing in English is actually more difficult because it’s not my natural language.

So, it was very natural to write it in Hebrew, and it’s also I wanted to do because Israel is not really a metal country. And the mainstream media always treats metal not seriously. Not respectfully, I’d say. From the 80s until now. And, when I started to do music, at the beginning I started to make music in Hebrew, with a very, let’s say, dark rock band. I found out that, you know, it’s too strange for the people here. So, very fast I switched to metal, and I did my metal albums over the years with my previous bands, and there was a feeling that “OK, they don’t appreciate what we do, so we’ll do it in English, we’ll spread abroad and…” more or less, fuck off! I didn’t need them to write about me in Tel Aviv if people were writing about me in Germany, USA, Australia and so on…

But it’s always felt like I should do it and, at a certain point I wanted to close this and do something in Hebrew, not from the position of someone who needs the media, but from the position of someone who did it without the media. And after twenty years of doing things without the media – forty years of bringing shows and distributing records and releasing albums outside Israel, I felt it was the right time to do a record in Hebrew and it made things very interesting, because all the parts you know from the English version, sung by Aaron from My Dying Bride or Fernando from Moonspell; all those parts were sun by Israeli rock artists whose names will mean nothing to you, but they’re very known in Israel. Not metal artists, rock artists. People… regular people who listen to music in Israel, they know them. But outside Israel, nobody knows them!

As I mentioned before, it’s a fine line, trying to offer lyrics that are oblique, because people can interpret them in so many ways…

Well, we have a song in the album called A year I would like To Forget. Everyone thinks it’s about the Coronavirus – all the magazines, all the questions, all the reviews – they mention this song and they say “of course, it’s a year that all of us would like to forget! It’s a song about the virus…” blah blah blah. I read it and it’s so funny, because it has nothing to do with the Coronavirus, it’s to do with my destructive relationship with my ex, that ended up with me being ripped off, totally and torn to pieces. It has nothing to do with Corona, it is about a destructive relationship that ended a year ago. That’s it. Everybody took the song in their own direction, and they think I’m singing about the virus. It’s in every review. OK, if they want to think that, they can go ahead!

I guess that, because of that, the songs start to belong to the listener..

I know that people never understand my songs, and they always prefer to tell me things that are totally in the wrong direction, but I’m so curious what they think the songs are about, that it’s always interesting.

In terms of writing the music, obviously you mentioned metal, but one of the things that drew me to the album was that it incorporates a range of influences – atmospheric post-punk, indie, doom… could you tell me how the music evolves – do the lyrics inform the music?

It changes from song to song. Some songs, the lyrics came first and on other songs, the music. It changed from song to song. We don’t have any kind of formula. We just… it can be this, and it can be that.

All these non-metal influences are very natural for me because my musical basket and roots are filled with bands outside the metal world. As a kid, as a teenager, I always liked… on one side Kreator, Slayer, Judas Priest and Morbid Angel. On the other side, I liked the Cure and Morrisey and Nick Cave. Even Prince. So, you know, having some influences from non-metal genres into our music is very natural for me. As metal as it can be, I will always be influenced by The Cure or The Mission or Bauhaus and Peter Murphey. It’s in my blood, I grew up listening to it as a lid, so it’s always there.

I think it makes for a more interesting sound in general – if you only listen to thrash, or what have you, then ultimately that’s what you’ll sound like. But if you bring in elements like The Cure, who are so atmospheric (like A Forest and pretty much the whole of Disintegration), then you step outside of the boundaries and that’s what captures people’s imagination.

I agree with you. It’s cool that you mentioned The Cure because, for me, the albums that were the biggest inspiration were Faith, Pornography and Seventeen Seconds. All of them from 81 to 84. Disintegration, of course, is a very atmospheric album. But the production is so huge that you can’t really be influenced by that. The production is so lovely and over-the-top that you listen to it and you realise that, although you love it to death, there’s nothing you can take from it and put into your basket, because you’ll never reach it. It’s too big! If you listen to albums like Pornography, or Faith or, as I said, Seventeen Seconds, there are a lot of elements that they did on those records from which, as a band, you can definitely take some ideas.

So, yeah, it makes the whole thing more interesting, I think, but it’s not on purpose. It’s not like “Ok, we’ll do a doom / metal band and then put all those influences in it” – it was never like that. I mean, I listened to these albums before I listened to metal. I came to the metal genre by listening to Sisters of Mercy or The Cure or Siouxsie And the Banshees and stuff like that as a kid. Then I discovered Master of Puppets or Seventh Son of a Seventh Son… The Metalheads that listened to gothic rock, they came to know gothic rock after they heard Draconian Times of Paradise Lost and they said “OK – it sounds like Sisters of Mercy… who are these people?” That’s the process that these people have – or when they hear Wolfheart of Moonspell, or Cradle of Filth, they start to go and search for bands like Sisters of Mercy or even Depeche Mode.

For me, it was the other way around. I listened to those bands before I knew Master of Puppets, so it’s always a yin/yang between this dark rock scene and the metal scene. Of course, it was done before… a lot of bands have done this combination, a lot of them. But I believe we brought something else to the table.

First of all, we come from Israel, so we don’t sound like a band from the UK or Sweden. The spice is a little bit different. Secondly, we do something real – coming from such a deep place – the heart. And if you put your soul into the record – I believe that people can hear it and they know when it’s something that you can believe, or if it’s just a cool album. Some albums that I listen to, I love them. I mean, the sound was not amazing, and the playing was not over the top, but I believed them do much. They put their heart and soul into it and, you know, take, for example, the first Katatonia album. Take, for example, Tales from The Thousand Lakes by Amorphis. Take, for example, Wolfheart by Moonspell. There is a lot of soul in these albums. A lot of authentic feeling. So, we tried to get this into our records – the same kind of agenda to put our soul on the table and say “OK – first of all, you have to believe what we want to say”. Then, the production, the sound of the snare, the guitar… OK, yes, everything is important. But the most important for me was to create an atmosphere that the listener will believe. That it would sound trustworthy and real.

I agree, I think that’s something very important in music that ties into atmosphere – and that’s what I thought was very interesting about the collaborations that you had because, with some records, the collaborations are very obvious and you can tell where each new musician walks on… but, in your case, the collaborators seemed very intent of serving the song so, to that end, they blended into the framework of the record. I thought that was really special and it worked very much in the favour of the record where it could, perhaps, in the wrong hands have detracted from it, if you know what I mean.

I definitely do… first of all, thank you for that – I agree with you. But it’s not a question of my opinion, but yours. I agree with you and I am happy that you say this. It’s funny because most of the reviews were really good, but there were two or three magazines… I have to mention it. It’s sitting in my heart, so I have to say it – they wrote something. I mean I don’t care if someone doesn’t like the record: “OK, it’s your right. I f you don’t like the album, fine.” But a song like In the Corner of a Dead End Street, they wrote that the song was written to specially serve Greg Mackintosh’s ability to play a solo and that we wrote the song especially to serve Sakis and Greg. And they wrote that it looks like we wrote the song one year before recording or a couple of months before the recording, just for the guests. And I looked and I said, “Really?! The song is 20 years old!” That song has been played on stages since 2005 and it’s on fucking YouTube! How can they say we wrote it for Greg? It’s 20 years old! Did we put Greg on hold for 20 years? And Sakis as well? For 20 years? I mean how stupid people can be! Let’s say they don’t know the song is from 2000 – OK, but there is a version of the song, live, on YouTube from 2004. How can they write that it was written a couple of months before the album for Greg? It was written twenty years ago, and recorded fifteen years ago, long before we thought about recording an album, not to mention having guest musicians.

I mean, people sometimes they feel that they have to say something – something, you know. So, I know I’m not supposed to take it seriously, I know…. I know. I’ve always said to bands – don’t take it seriously. As long as they write your name without spelling mistakes, it’s fine! But, you know, it pissed me off. You can write you don’t like the album – OK, good! But to write that we did it just for the name dropping and we wrote the song one year before… really?! Do a little bit of research, just a little bit!

So, I’m happy that you say this, and, at the end, people may be interested because of the guests. I’m not stupid, I’m not a kid, I understand it – but, they will continue to listen to the album more and more, not because of the guests, but because of the songs. You can be interested because of a guest – I can tell you about a band from Argentina, that had the guy from Cradle of Filth and Tom Lindberg from At the Gates on the album, and you’ll think “hey! I want to listen to it!” and, OK, you want to listen because of the guests. If the songs are bad, you will not continue listening.

So, the guests may open the door, but the song will keep the people in the room. It will make people stay in the room. If the songs are good, they’ll stay in the room. Maybe they will enter the room, because of the guests. OK. That’s marketing. But, if the songs are bad, they will not listen to the album. So, the most important thing for me is the songs. And I can tell you 100% all the songs were written with no guests. All the songs were written long before we even thought about guest musicians. And some of them were even recorded without guest musicians and then we had a guy in.

So, I know, and I understand that, being a band from Israel, having a debut with this list of people, some people can decide they want to find a way to slap us, you know. Some people are like this, I understand it, but honestly, all the songs were written long before. Not one year before Greg mackintosh. Not five years.

It’s difficult because, as you say, having guests can swing both ways sometimes, because you’ve got that person who brings something to the music, and of course you want to tell people about it, but it can then inspire people to incorrectly focus on the name.

I think the bottom line is very simple – do you like the songs or not. That’s the bottom line. If the songs are good, and people like it, they need to listen to the song. If the song is good, I don’t care if they bring twenty guests or no guests. If the song is bad, I also don’t care, because the song is bad! The bottom line is always the song. Always! That’s what makes people buy your records. So, you know, I tried to bring people in that would have something to do with the music that we play and who will add something from their own into our body of art. With Jeff Loomis doing his part on Into the Mouth of Madness – he brings Jeff Loomis into the song. You’ll hear that it’s Jeff Loomis from the first moment. You’ll hear it’s Jeff Loomis of Nevermore, now Arch Enemy.

My final question is that the album has an interesting, even unique, hand drawn or painted (I think) cover – how did the artwork come to be chosen and was it a challenge to find something that represented so personal an album?

I’ll tell you because it’s very interesting. Of course, we started to think about the cover art and what I did was I tried to look at the websites of the local, famous designers of bands and, to be honest with you, over the years, metal covers of the last twenty years are not as strong as they used to be. They all look very nice. They all look very impressive, but not a lot have a strong character. I used to say it even straighter – if you replace the logo of the band with another and no one will understand the difference, because the covers look so similar. OK, you want to buy this art – OK, buy it, put your logo – here is the cover. I was looking for something. I was looking for something that reflects the marriage between the two worlds we spoke about previously. On the one hand it needs to be dark and doomy, on the other hand, it needs to look like a gothic post-punk album from the 80s. Something that combines these elements. Something that combines those two worlds. And I couldn’t find a designer wo could make it for me. Then a friend of mine was staying, what about Ziv Lenzner is not a designer, he’s an anatomist. He’s an artist, a professor of anatomy at the University of Tel Aviv and, in the past, when we were young, he was a singer of a death metal band in Israel. When we were kids. But he’s doing a lot of artistic stuff for his own research and works at the university. He’s a friend of mine, and I never thought of him as a designed. But, Ziv grew up with the same things as me. We grew up listening to Bauhaus and Paradise Lost; Iron Maiden… together, when we were kids. And he would understand me. So, I called him, asked how he was and played him the songs and asked if he would do the cover and he said he was into it, he’d make it and he understood exactly where to take it. So, he did for me the ideas and then, when I saw the ideas, I thought the ideas he had for the album, I knew in seconds he was the guy and it’s what I wanted – the vibe I wanted. And, that’s the guy who did the cover artwork. He’s a professor of anatomy and he is just having an exhibition right now in Tel Aviv, which has nothing to do with metal music or metal album covers. He is a metalhead though, but not working in metal. This is the first album he did the design for. He also did the video art for our shows, which of course, no one can see because of the virus.