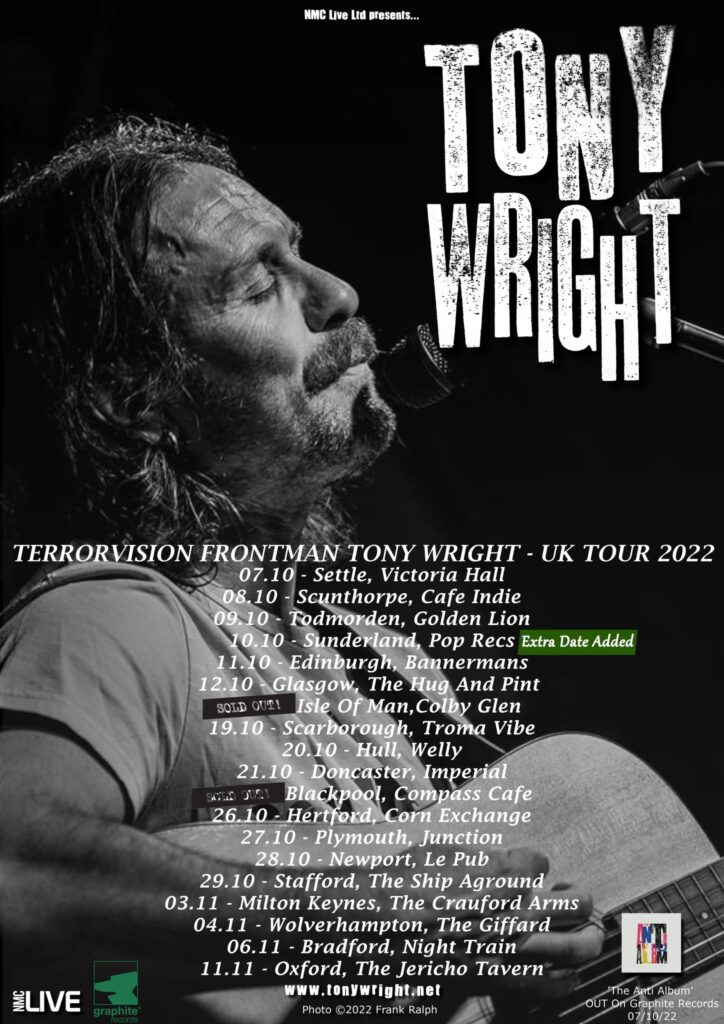

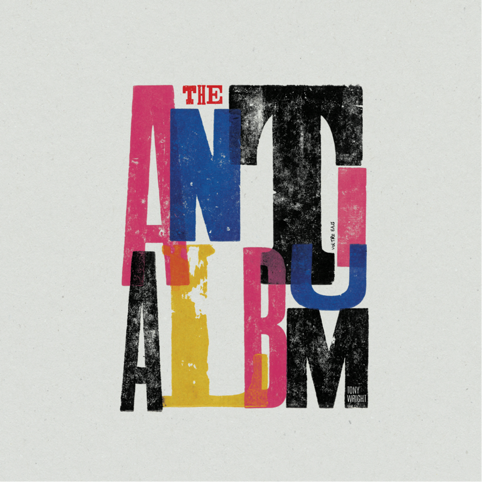

Tony Wright, frontman of Terrorvision and solo artist, is a born storyteller. His passion for his music, and for his art (he hand-printed the cover) shines through and, with every question, he has a response that digs deep into the reasoning behind an album that is easily one of the highlights of the year. Named The Anti Album for reasons that will become clear, it’s an emotional journey that demands you sit quietly for its forty-odd minute run time, and to spend time in the company of the album is very like spending time in the company of Tony himself. You can read our review here, but first, grab a drink, settle in because Tony’s got tales to tell…

Just very briefly, I grew up hugely into grunge and rock in the early 90s, and I remember that Terrorvision were huge and managed to play just about every festival I went to, which was always great fun. But obviously Terrorvision were larger than life and I guess, within that, you had to play the frontman role…. So, what I wanted to ask is whether you felt, when you started playing solo, that you had more of an opportunity to be you, rather than this larger-than-life persona?

I get where you’re coming from. It’s a different thing, I suppose. Terrorvision was four lads from Bradford that came from different backgrounds of music.

We all like rock music, don’t get me wrong, but I grew up listening to… and I still say that my favourite songs are by people like Elton John and Bowie and the Carpenters and stuff like that, although I do like my Zeppelin and Free.

I kind of inherited a record collection off my sister, who’s four years older – she went to college when she was seventeen and I was twelve / thirteen / fourteen maybe. Anyway, she went, and I remember her taping all the records onto cassette, so she could take them to her halls of residence, because she got a cassette player to listen to them on. And I was left at home with this record collection that she had got from wherever – pinched off boyfriends or whatever – and I spent years just going through that record collection: everything from Leonard Cohen to Lynyrd Skynyrd and Zeppelin, Free, bad Company, Donovan… you know, it was guitar-oriented music. There was a lot of acoustic stuff in there, and there was a lot of all-out rock music.

So, yeah, I used to stand in front of the mirror with my tennis racket because I didn’t have a guitar, my first guitar was a Slazenger and I used to strum it and headbang!

I think we all did that!

Yeah, we all did, but then we were growing up in the 80s you see… and in the 80s – rock music sort of took a side to electro-pop, where guitars were put down and people would stand really still, playing keyboards. Now, I know that I said my first guitar was a tennis racket, because I wasn’t allowed a guitar – I didn’t have a guitar, so I had to strum a tennis racket and pretend. But I never got the urge to get the ironing board out and pretend it was a keyboard!

I loved the guitar because I found it more honest. More in your face. More real than the synthesizer. Don’t get me wrong, some of that pop music – Human League for example – is great, Gary Numan… there was loads of great synth pop music, but the majority of it was boring!

So, yeah, coming back to the question and Terrorvision; you had me, with that background, singing; you had Mark, the guitarist, who’s into Motorhead and AC/DC… he also like New York Dolls; Leigh liked Kiss and Hanoi Rocks and the New York Dolls, so them two were linked through that. And then Shutty liked Motorhead and AC/DC. And when I auditioned for Terrorvision, I asked what to sing, and they said “teenage Kicks” by the Undertones. So, we were never going to be a standard rock band.

We grew up in Bradford, where bands dressed up in Spandex, but we were just four scruffy oiks, who sang our hearts out and did our best. That was it, really. I suppose we weren’t that dissimilar to grunge, but I always said grunge is a bit more intelligent than me – I like words, and if I don’t understand the words, sometimes I think it’s because they’re crap. Like, if I don’t understand a song that’s about dragons and love of yesterday’s shadows and castles, then I think it’s drivel, right? But, when you get the likes of Nirvana, I’d read it and the words said nothing to me. But then I thought that Shakespeare meant nothing to me either, so I figured I was just too thick for grunge, but I love it!

So, yeah, we were in that same camp. It was an antidote to the spandex and all the “whoo-hoo baby” kinda sexist, misogynistic, very heterosexual rock music that was out at the time. It was all old men singing about chasing little girls, wasn’t it? And, yeah, now that’s the remit of rap music. So, rap music took over the embarrassing mantle with that one… not all rap music.

But yeah, I’m a lot blunter in my lyrics and my delivery. So, while someone could be singing a song, conjuring up all these things with words that I couldn’t understand, I’d be telling you about my house and how many bedrooms it had and what colour bathroom it had – quite normal.

There was a song on the last album – the blues I think- and I remember reading an interview with you at the time, where you talked about the track being about someone having a really good life but feeling like they had to have a harder life to create that sort of music.

It has to be taken seriously, that kind of music. You can’t come along and say, “hi, I’m Quentin, I’ve got the day off because my dad owns the business; his chauffer’s bought me down, and I’m going to play the blues…” It’s not going to happen, not knowing what life’s like. So, the song is about someone who throws everything away so they can be taken seriously as a blues musician. If you’ve lost everything and ended up in the gutter, people will take you seriously as a blues musician, because you can’t have the blues when your dad owns the business.

I joke about it to this day, and I still introduce it is that – I tell people this is basically a song about how shit life is when you’re lucky, but I was singing that song years before Adele! When Adele brings out an album about how hard her life is, with all her billions in the bank, it’s sort of like [in a voice dripping with sarcasm] “oh dear, never mind!”

So, yeah, I’ve always written songs about things, I always think that the blues is a true story that I’ve made up myself!

So, when you’re developing songs for your solo stuff, is it still very much you with a nylon strung guitar, and then the band fleshing out as needed?

For the solo stuff, I don’t play with a band. I write two guitar parts. One will be a melody that intwines with another melody – another guitar part – so, you can drop one out, and you get a third part, and then you drop the other one out and you get a fourth part. Play both together, you’ve got the first part. So, you have two riffs, and you can get four or five feelings out of that.

So yeah, I play my guitar at night. I don’t have a telly, so I just go up to my room, I get my guitar out and I play it. And I know what the basic chords are called, I know A, B, C, D, E, F, G… probably my minor chords, but if someone says, “play a seventh”, I’ll probably just play the chord six more times! I don’t know what they’re on about. And quite often I’ll spend my time doing these chord shapes, because I like the way that note sounds, but I want another note, so I’ll do these ridiculous shapes – my tongue’ll be stuck out and I’ll be like that [adopts pose that looks somewhat like Richard III trying to play Twister] thinking this is the best guitar chord ever, it’s so amazing. And I’ll play it to someone, and they’ll be like “yeah, it’s a chord, why don’t you just play A minor though?”

And I’ll say “you what? It’s A minor?” And then I’ll double down and play the complicated one.

So, that’s what I do, I play my guitar all the time, and I truly do believe that all songs just float around above us. You don’t write a song; the song hits you and it makes itself known to you. If you ignore it, it’s your loss. Or not – it might be a rubbish song! But, if you ignore it, it’ll fly over your head and bang into someone else’s head, and they’ll sing it and you’ll hear it and think that’s a good song, as if you’ve heard it before… but you haven’t and you blew it.

So, that’s how I feel, and sometimes I’ll listen to a song that I’ve written and think “wow, I’d never have done that. I’d never have created those words or that part.” I do believe that. I do think it sort of comes in from somewhere else and you just have to open your mind.

I’ve been lucky. With Terrorvision, we brought out an album after we’d probably been together for five years, just writing. Then, the second album comes out and you’re working with a producer, and you have all those other ideas that you never did anything with, and you work them up into songs. Then, the third album, the record label is like “that last album was really successful, do it again!” And you’re like “well, why? You’ve got it if you want to hear it then put it on. We want to do the next thing.”

So, you do an album that’s the same… and there’s certain bands that do it now. They’re massive, but you only need one album by them because you’ve heard it. You don’t need to buy a second album, it’s just like the first. Sometimes it’s best to wait for the Greatest Hits! So, there’s a part of song writing that I kind of leave to the ether, you know “let’s see what happens”.

But yeah, I have a thing called the “bag of riffs”, which is an imaginary bag, but I can tell you what colour it is. It’s a hessian sack and it’s got a drawstring top on it. A bit like a pump bag when you were at school, but it’s coarse and it rubs your hand. It’s called the bag of riffs, and sometimes when I play my guitar, I’ll find a part and then I’ll just start playing it and it’ll do its own thing, and I’ll end up in a different place to where I started and I’ll think “wow, that’s really good” but it doesn’t go anywhere from that point – it’s a good verse or a good chorus, or a good bridge, but it doesn’t go any further than that.

So, I put it in this bag of riffs, which is an imaginary place and, when I get to a certain point in another song, I’ll look through my bag of riffs and there might be a riff that fits on it perfectly, or there might be a riff that sits behind it perfectly. Or it might be the same riff [laughs] and then you’re on a roll, really. That’s how I approach writing songs.

With Terrorvision, we very rarely write a complete song for Terrorvision. We’ll make the bones of a song, and then the whole point of playing in a band is to have other people interpret it. So, I’m not going to tell Mark how to play guitar or Cameron how to play drums, or Leigh how to play bass. But I can say “I’ve got this riff, I kind of like it and it goes with these words” and then I have to let go of it a little bit, because it has to go with how other people play. Then I have to accept that. If I don’t think it’s getting better, I have to say that. If I think it’s getting better, I have to say to myself, “see, you could’ve done it better”. And it’s just a process. It’s a process that some people do, and some people don’t. I’ve never sat down and thought: “I’ve got to write an album”.

Well… we did actually, with the likes of Regular Urban Survivors, but then Shaving Peaches was the album after, and that was when we were allowed to experiment, and we did, and that ended up with Tequila getting to number two; and we fell out with the record label, so that was the end of that. No bad thing!

I get that idea of songs kind of hitting you, and also taking forever to gestate, because it’s so often the case that you’ll be fiddling around with something and it’s not going anywhere, so you sing into your phone or throw it into your bag of riffs, and sometimes years later you come back to it and it suddenly works, which is so cool.

Yeah, my bag of riffs is an imaginary thing, for others it might be a computer. Different people… I am sure everyone has a bag of riffs; they just do it their own way. Sometimes, you’ll be writing and, like you say, you’ll look back… and I genuinely root about in the bag until I find what I need – and it’s always at the bottom. And then, when I pull it out, I record that on my phone to make sure that it fits with the other part I’m doing – that it sits over it or underneath it properly. And if it doesn’t, it goes back in the bag of riffs [laughs].

And then other songs, I always say, I’ve got three-minute songs that took two minutes to write. It’s there. It’s almost instantaneous. I have one at the moment that I’ve not recorded. My son, he was working in a bar in Leeds, and he was walking home through Hyde Park in Leeds at like three or four in the morning. It’s dark and there are shadows, and this guy shouted, “do you want a drink?” and held up a bottle of cider form his park bench. And my son was like “you’re alright, thanks!”

And the guy shouted back “I just want to chat!” And my son said, “that’s a weird thing to shout at four in the morning – what do you want to chat about?” And he said, “I bet you think I’m a bum don’t you, because I’m sleeping on a bench…”

And then he told this story of how he actually had a house in Middlesborough, and a car, and a job, and a wife; and he ended up in Leeds on a bench, because he’d also met a girl in a bar. And she was called Jennine and his wife was called Jeanette and he said he just knew that one day, he was going to get the names wrong, and that was his life not worth living anymore. So, he said he’d rather be on a bench in Leeds. So, I took that story and, straight away, that’s a song called Jennine and Jeanette. And that could be a thousand years old, passed down through the family, but it’s one of those things we all go through, isn’t it?!

When you did the first record, you were talking about “anti-production” and being very raw and now, this third album, is the “anti-album”, is this part of trying to demystify the idea that making music is this big complex process? Or what’s the idea behind it?

So, the anti-album is… there’s this formula… and don’t get me wrong, we all use it, whether we know it or not… we all use a formula that works for us. But there’s lots of different ones, and different ways of thinking. So, when I was recording this album, I was really lucky, I went to Scotland and I recorded all the sounds with Edwin Collins, on his old Neve desk. It’s analogue, and we had guitars form the 1940s, strung with strings from the 70s. But you ‘d find the guitar that you wanted, and Edwin’s a genius and he’d say, “if you’re going to use that guitar, we’ll need these two mics going into this box, back into the channel and into the speakers” We didn’t have to experiment with the guitar because he knew. He knows his gear inside out. So, six days of quite intense, short-day recordings meant that I had the sounds, but they weren’t in any way mixed. And we weren’t going to be able to mix them there, which would have been interesting, but we just didn’t have the time and they had other projects on.

So, there’s a lad that I’ve known since I was probably twelve or thirteen, called Steve. Growing up, he was a guitar virtuoso. We used to go to a bike shop – we called it Moses’ bike shop because the owner looked like Moses. He had a beard and long hair and string tied round his head – and he was called Malcolm… and you’d go in there and you’d buy cow horns for your bike, which were these big handlebars you’d put on. But sometimes, he’d have a guitar in there, or he’d be playing a guitar, or there’d be people in there with guitars or selling guitars or buying guitars. And Steve was one of those people.

Anyway, as a kid, I asked if he could play Stairway to Heaven, and he played it, so I thought this fifteen-year-old lad was the best guitarist in the world! But he was into like Van Halen and whooping and hollering and high kicks and tight jeans and paint everywhere, and then he said he saw Van Halen on The Tube and he literally locked himself in his room for two years, because he wanted to play like Van Halen. And he was an amazing guitarist. An amazing session guy. He’d be up there, if you were to put him in a competition, he’d be well up there. But he was never successful in the bands, and he ended up – his dad was trying to make him get a job, and he said, “please dad, I just want to do music” and his life was going up and down because of the turmoil music brings with it.

You know, music… It’s not a poison chalice, but it’s a cross to bear, it’s like… you can’t not do it, it’s an addiction. Anyway, so he was working in a cellar in Leeds with some people and they wrote and recorded an album that sold millions, and he went from struggling to being very successful. And now, he’s one of those people – X Factor will send him some protegees to work with in his studio, and he’ll write songs with them. Capitol records ring him up and ask him to go over to work with an act, and he always says he doesn’t want to go to The States, and they basically offer him the top floor of Capitol Records and the basement, so he’s got the whole lot. But he writes pop music, really. It’s not rock music.

And so, I thought it would be interesting to see what he would make of this approach. So, I’ve not put bass guitar on this album. It didn’t need it. I’ve played in bands long enough that you think you need to have the four components. But you don’t. Space is an important instrument or effect. Leaving that open space – that time to think – that, like, awkward moment is important. Awkwardness attracts attention. And I wanted to make an album that you listen to. That you put on, like…

When I was a kid, I’d save up. I’d know a record was out on Saturday, I’d save up, I’d go to town on the bus, I’d buy it and I’d get back on the bus and I wouldn’t do anything else. I’d look at it all the way home on the bus, and then I’d get off, I’d walk into the house, I wouldn’t talk to anybody, I’d go straight into the bedroom, I’d put the A Side on, get the needle in the groove and I’d sit on the bed and I’d look at the cover. Front and back and middle; inner sleeve, I’d look at it.

Twenty-seven minutes later, I’d flip it over, and listen to the other side and I’d still look at it, the artwork, I’d read the lyrics. I was never really into who produced it or the names of who was in the band, I’m not a collector of things like that. But it was… I was invested, the whole journey. Giving a little bit of yourself to the record and then getting all that record back in return. You know? It was an amazing feeling.

Anyway, I was speaking to Steve, and I said, “I know there are all these rules now, where you’ve got fifteen seconds to be in the chorus…” and he said: “Tony, it’s eight seconds. Eight seconds.” And I asked why, and he said, “because of Spotify.”

Spotify, Alexa, Google – people don’t have to invest in it, so it’s on in the background, and if it doesn’t grab the attention in eight seconds, they just say “skip”. And I thought, well, they can have that kind of music. I’m not making it for them. I’m making it for the person who wants to listen to something. To sit down and put something on. This isn’t an album where you get in at the lobby and you get off at the third floor and that’s all it ever does for you. It’s an album where if you sit down and listen, it’ll make you smile, it’ll kick you in the belly, it’ll say things you don’t want to hear, and sometimes you’ll think “oh, that’s a funny twist on a line”.

I’ve thought long and hard about it. When I sang, I sang my heart out. When I played, I put everything I had into playing it. It’s not background music. Don’t put it on and try and do something. Put something else on. If you’ve got the time it takes to appreciate it, or not (at the end of the day, you might think “that was a waste of forty-five minutes”) but at least it’s honest. It’s… I’ve sang songs with “doo-whops” in it, I get pop music. But this was… It’s like it’s an art form.

I do a lot of printing. I used to be a printer and I used to print sticky labels that told you there was 3p off of stuff at Morrisons – I used to get 3p off of everything in Morrisons! [laughs] because I printed the labels. So, yeah, Bernard Matthews’ Turkey Roasts, that’s the kind of crap I printed. I printed litter, right? It came out of my printing press; it’d go on a bread packet, and it’d go in the bin, and it’d go into landfill. And I knew I was printing litter. And now I don’t print like that anymore. I print for pleasure, and printing is an artform, whether it’s printing words or lino cuttings… I’ve got some bits and pieces here [holds up a succession of exquisitely cut lino prints of famous artists, including Nick Cave and Lemmy] So, this is the kind of printing I do now, and I purposefully don’t print letterheads or commercial stuff, because I don’t want to make things that are for the bin.

So, yeah, this album’s the same. I don’t want it to be just there. I want people to listen to it or don’t bother. It doesn’t bother me if… if you listen to it and think you don’t like it, that’s cool. I don’t mind. There are some the biggest bands in the world I think are crap, so I don’t mind.

For me, I went through it four or five times to try to get my head around it before writing a review, and the way I felt about it is very much what you were describing earlier – I’m still that person who goes to record shops and I still open up the sleeve notes and I look at everything – and it feels like one of those late night journeys, with songs like Dreaming I’m In Love, which is very bittersweet, because the title sounds lovely, but the lyrics are quite clear that only the protagonist thinks they’re in love, but they don’t understand the concept… and then, at the end, you’ve got Gamble, Drink and Smoke, which has a Buddy Guy vibe to it and is completely unrepentant…

It’s like, when Steve said that to me about 8 seconds – as a modern-day pop producer who is aiming for radio. That’s not what I’m aiming for. If it was a success, and Cannonball went to number one in America, or what’s that song… [sings a snippet of a track] … Hearts and Minds – if that got big in Germany or something, I’m not saying I wouldn’t be happy. I’m not saying don’t play it, but when Steve said it’s eight seconds, and this is why it’s the Anti Album, I went “right, we’re going to extend the intro to make it forty seconds” and he’s like “But Tone, it’s more instantaneous.” And I was like: “well, how do you set the scene for a song?” You’re going to tell a story – but if all you’re going to say is “oobie doobie, who loves pies?” If that’s all you’re going to do, that’s fine, get to it in eight seconds. Sing that for three minutes and it’s done, and the kids love it. That’s a different thing.

But, you know, some of the songs here, like Gamble, drink and smoke, I’d class that like writing a book, because it’s got a start, a middle and an end, a twist, and it tells a story. Songs, like All in Our Heads, which is a song about writing songs – it’s like where did that song come from? I’d say that was a short story. I wouldn’t even classify it as a song, really. It takes you from Dreaming I’m In Love to Heaven.

And the album, right, some people have heard this, some people haven’t, but when I told them, they were like “I knew that, but I didn’t know I knew it”. So, the album starts with the last song. The last song in the story. So, it’s like here’s the end of this story and then I’m going to tell you how we got there. So, Sleep plays, and then track two, which is Nothing to Write Home About, which is telling you how we got to this point where all he wants to do is sleep.

So it starts, and he’s a kid at school, and it says: I went to school, I got a job, I got a car, we got married – he did all the things he was supposed to do, the societal things – that song has a bit of vibe of three old school mates meeting up. They haven’t seen each other for thirty years and they’d gone back to the school reunion and they’re asking each other what they did. And the first guy got a job and a car straight away, met a girl, got a house, got married had kids and that lot. Then the other two are like “yeah, yeah, that’s what I did”. And then one of them goes, “just let me take it from here. See, actually, we did well for ourselves, we got better jobs, we got bigger pay rises, we got a bigger house and the cars got faster… Then she got bigger ideas, met a guy, and I sort of fell off the back of that.” And the other two go “oh my god, that’s our second verse as well!” And then the third guy says, “I go on holiday twice a year” and the other two look at him and say “Ibiza” and he says “yeah!”

And they realise that they set out from the same point in an explosion that blew them in completely different directions, but none of them took a risk. They all lived exactly the same life. None of them have got a story that’s like “do you know what… and I thought I had enough of this guy, and I pushed him down the stairs and he happened to be Liberace” or something like that… do you know what I mean? There’s no… they didn’t do anything that they weren’t expected to do as human beings, and I guess society runs on that, but you need to break out of the mould. You need to be free. You need to have freedom. There’s nothing against living that life and living happily ever after. You know, some people can. But the world’s out there for the taking. Don’t ever think that there’s nothing over the horizon. Don’t be grateful for the bottom rung, aim for the top. Even if you fall off and land on the bottom rung, at least you’ve got the story to tell. It’s a call to arms. To go out there and grab life by the horns and do something with it… If you want. So, the end of that song is she’s gone, there’s nowt to write home about, there’s nothing left here, and he’s left on his own, in a limbo that I’m sure we all go through. It doesn’t have to be at the end of a relationship, it could just be being a teenager. It could just be being a normal bloke from Bradford. It could be any of these things, but you get it wrong.

He gets it wrong; it doesn’t matter what he does, he’s making a bloody cupboard and he’s taken the advice to measure twice and cut once. Well, he measures it twelve times, cuts it finally and it’s still wrong. He’s unlucky when it comes to love. He’s just going through a bad patch.

Then, the next song after that is Buried You Deeper. So, he’s trying to take all those things that have been negative and metaphorically he’s burying all these memories that hold him back. But, like anything, when you don’t want to see something anymore, something will uncover it and scream it from the rooftops. You know, if you sell a guitar that you’ve loved and you’ve paid a lot for and it feels special to you, you’ll be lucky to get owt for it. If you’re looking for a really special guitar like that, it’s £10,000. If you’re not looking, your mates got one in his garage that you can have. It’s that example of don’t go looking but always be aware. So, he’s got it wrong. He gets it wrong. So, he’s tried but he’s in limbo and he realises that life – you start it, you survive it, you get to the end of it and that’s it. He’s not living it; he’s going through it.

So, that’s where the Dreaming I’m In Love comes from. He’s been unlucky, he’s trying to bury everything and then, when he’s dreaming he’s in love, he’s happy. But when he wakes up, he’s on his tod, and then he says to himself, “if I’m dreaming I’m in love, I’d rather not wake up at all”, so he goes back to sleep saying that.

Then, All in Our Heads, is about writing songs. So, he’s like, this is it – just try to be positive. This song’s in my head. I’ve not heard it on the radio. I’ve not got any music in the house, but it’s just there. So, that’s about writing songs. Then he goes into Heaven.

Now Heaven and Hearts and Minds were the other way round, but I thought after Dreaming I’m In Love and All in Our Heads, I needed something more obnoxious to pick it up, so I put them the other way round. Heaven should probably be the last song, because he’s at the gates of heaven, isn’t he? And he’s saying to Saint Peter, “nah I don’t know what you’re on about mate, I’m just here for a look around and then I’ll go back again!” And Saint Peter’s saying, “no, this is it, this is the end” and he’s saying, “nah, I’ll tell you what I’ll do, I’ll get a few selfies with the big man, get him to sign some stuff for my mates and then I’ve got somewhere else to look around anyway before I make a decision.” It’s just a very Bradfordian way of not accepting you’re dead when you get to the gates of heaven.

Hearts and Minds was actually just a lockdown song, because I wrote this in lockdown. It was just one of them songs, where we’ve talked about writing songs and he’s gone to heaven, so after that, it’s just a song. So, after this lockdown, it’s asking if we’ll all be together again, So, it started quite simple and sparse, but by the end everyone’s singing because everyone wanted to know if we’d all be together again and if things would be the same again, but they’re not, so… I quite liked the old normal. The new normal isn’t doing it for me, but I’ll get used to it.

Then it goes into Gamble, Drink and Smoke. I used to have a newspaper clipping on the back of my shed door, from a local paper about this right miserable, miserable, weaselly faced old bloke who was like 101. And the Telegraph were interviewing him because he’d had his telegram from the queen and they asked him “do you remember the Victorian times?” and he said “aye, I remember Victoria”.

They said, “do you remember when roads like Banningham lane were a dirt track?” And he said “yeah, there were dirt tracks, and it was horses and carts.”

And they asked if he remembered the first cars and he said yeah.

So, they did all this interview, and they asked him at the end what the secret to his longevity was and he said: “I smoke twenty times a day and drink half a bottle of scotch!”

And it was hilarious, because they are the people who live forever. The Keith Richards – so yeah, the older he gets, the more debauched he becomes. He’s dealing drugs. He’s womanising. An absolute chaos, mayhem guy! I just thought that was great because it’s not what people want to hear. They want to hear people say that they jogged all their lives, or that they drink two litres of water a day, or they only eat greens. So, I thought it was funny, and (in the song) from that point on he just gets more debauched – which is poetic license. I just made him more debauched, and he was eventually growing his own weed and brewing his own shine. But at the end, he sort of goes into the basics of it saying that that was just his cards. That was his life. That’s what he got dealt and he can’t change it, but he’s had enough. He’s saying basically that he wants to sleep.

But, at the end of that song, I had to put a twist on it, because I put Heaven in earlier. It needed that little kick up the arse. So, Heaven was already used, and I thought he can’t die at the end, so instead he says “I’ve always been this way, ever since I was a lad, I’ve never known anything different, it’s the only life I’ve had” and then he says, “if you don’t believe me, you can ask me dad!” Which makes you think, oh my god, if they’re interviewing him and they can ask his dad! It’s a light-hearted twist at the end, just to show that I’ve got a sense of humour. It’s a funnily reality and all he wanted to do was stop waking up every morning, like: “bollocks” It’s another day!” He’s had enough. So, then we’re back at the start.

The music has to be a theme tune of the story that you’re telling, so I think… recording with Edwin Collins, he just has the ability to hear the sound – if you shut your eyes it could make your hot, it could make you think the sun was beating down on your back and that there was a desert in front of you, because he uses all the right instruments that you associate with all that. And it could make you cold; or it could make you excited or make you speed up, or he could make it slow motion. That’s what the music side of it does.

You know, it’s like seeing it. You used to get these pictures, like under the sea, and then you had all these rub-on transfers of divers and sharks – did you have them?

Yeah – I’ve not thought about those in years!

You’d get outer space and rockets, wouldn’t you? You’d draw them on with a pencil and they’d stick.

Wow, yeah – it was like 84-85, I think – I used to stick those stencils everywhere, on cupboards and stuff, and your parents would be screaming at you…

Yeah, and you’d scratch it off! So, that’s the music – it’s that background and the words are the way you put those transfers on. You can put them on in lots of ways to tell different stories. The divers might just be divers. The sharks might just be sharking… but sometimes the sharks attack the divers. I’d do half the leg transfer and then the other half floating down or in the shark’s mouth [laughs]

It sounds like you had a lot of fun in the studio layering things, particularly on (I think) Get It Wrong, there’s a lot of space like you said, but then there are those cymbal washes and the piano coming in. It’s a really lovely song and it sounds like you had fun playing with those elements.

Yeah, well you have to remember that we take these songs on tour, and I don’t want to stick loads of stuff on there that we don’t take on tour with us. The songs are the same songs, but maybe heard slightly differently when you play them live. On that one, originally it was just the two guitars and a drone, which was a BV that would go [vocalises drone] it just had that sort of [imitates drone] vibe. I don’t know what that instrument is…

It kind of sounds like a didgeridoo.

I suppose it’s similar, do you know a Jew’s Harp is?

Yeah, yeah, yeah

It’s kind of like that low drone, and then we put some piano on, took a load off and then I think I took all the piano off and then got the wrong mix back and the piano was in there and that made me change my mind.

I’m glad you did

It’s just me, messing about one take on a keyboard going through the whole song and then you can just drop it in and out where you want it.

I think it really adds something. It doesn’t have to be anything huge, but it adds something.

Well, there’s no following the notes, playing the melodies. There’s no real… it’s not… the piano in that is not really involved in that song. It’s just doing something else. If you just took the piano track, it’d be quite hard to sing along to [laughs]

And then you’ve got Heaven, which particularly for an acoustic song is really quite heavy – it’s got a lot of grit in there.

I think, playing on an acoustic guitar, really strumming hard, is as heavy as any Marshall / Les Paul combo. I think it’s a different kind of heavy. But you know, they didn’t have speakers when they were writing shit like the 1812 overture! They had to do it with a lot of instruments, but they used the sounds of those instruments.

So, an acoustic guitar, being strummed, like attacked is awkward, and I think the awkwardness makes it angsty and that sense of angst makes it good. I also have an old Telecaster, I think I gave it to my son actually, and it was a Squire one. I bought it right back in the 90s and it didn’t work originally. I think I threw it somebody and it ended up under the stage. And when we were got it back again, there was all these bits missing and chipped off, but it worked! It didn’t work, but it does work now – since I threw it. So, with that, I have a little 10” valve speaker. It’s a Gibson amp, it’s ace. It’s just valves, volume and tone. It’s ace and that sounds heavy! Because it sounds like it’s trying to claw its way in through the door. It’s like the obnoxious brother to the Les Paul / Marshall combo that can sing really well, that’s perfect, that listened at school!

I was talking to someone recently who recorded their whole album recently using this little 10w amp, with a mic stuck into the grill – some of the sounds you can get is awesome. But it’s also happy accidents, it doesn’t matter what you use as long as it makes the sound you want.

There’s a lad – do you know of Willie Dowling of The Dowling Pool?

Yeah…

This isn’t what Willie does, this kind of music; but as I got Steve to mix it, who’s a big pop producer, I thought it would be really interesting to get someone like Willie – to send him stems and see what he came back with. If he took these songs – and these songs, I used to refer to them as baby songs, just me and a guitar – that was the first inkling. They’re like stumbling footsteps of the song. It wasn’t there, it couldn’t feed itself, it wasn’t a fully formed song and I played it and played it and I added to it and took away from it, and then, after I finished it and cut it right down to be as a sparse as I could. So, they’re no vague songs anymore, it’s almost like they’re adult songs, but someone else could dress them for me. I think you could use a lot of production and techniques on these songs to make them metal, or pop or dance. You could make them whatever you want – a song you play on an acoustic guitar.

You have to have a lot of trust with producers, especially if you’re working remotely, because you can lose a track to them for… sometimes months, and the amount they can change is remarkable, like you said.

I did try a bit of it remotely, but it wasn’t working, so I sat in the studio. Because the people who I’m there with – I’d say to Steve, “do you like it, Steve?” and he’d say, “I only like it because it’s you!” He only liked it because it was me, so it must be the way I am, but I don’t think he liked the way I approached it, because he wanted to chop off the intros, loop the choruses… “that’s a great chorus – again, and again, and again!” Maybe not to that extent, but yeah, I like the fact that these songs… I like to hear what people would do to them.

So, I only have one last question for you which is about the packaging – it’s such an important part of the process. Obviously, you showed me those vinyl cuts earlier, so was the artwork all you on this?

Yeah, I like printing. So, the first album that I did, was a block that I did where I just rolled some orange ink on the piece of paper and then printed the cover, quite small – CD sized. But, because it’s letterpress, it’s really clear edged, so it blows straight up with no pixelation. So, I did that.

The second album, because I played electric, the cover was done by a friend of mine called Drew Millward who’s an artist. He does loads of stuff like Foo Fighters – loads of bands. I said to him that I wanted to take it form acoustic to electric, so I wanted hills (because hills are acoustic – hills and outdoors), so they were made out of guitars and drums. And then, in the background, was the city, which is all electric. And it’s like the necks of Fender guitars, tower blocks and with a plane flying over the top. And that’s all done digitally – he draws on a tablet, I think. But he’s great. He’s really good. His artwork’s really distinctive. And then there’s a picture of my old dog and my camper van and the journey that we took from the acoustic to the big electric. But we came back from the city, anyway, for this album.

And then, this album, I love the letters that I have in my collection of letterpress letter because I look at them… Oh my god, I sound proper Spinal Tap now [Laughs] I look at them and they’re maybe one hundred years old and one hundred years, what’s happened? What did they tell us, what did they say? These letters were used for making posters. A hundred years ago… eighty years ago, 1942, they were telling us to dig for Britain. They were telling us that we are at war. That A that I had in my hand might have been the A of War – what a horrible, horrible thing to tell somebody. Twenty years later, it might have been the A in Beatles Playing the Town Hall. You know what I mean – the same letter, and it’s in a different order and now it’s saying Beatles! So, I have a real passion for these things. A font of type is a family of type, it’s told so many stories and said so many things good and bad. They speak different languages; it just depends on what order you put it in. So, I just had some really nice letters that were… it’s called a bastard box, because they don’t belong to a full font. So, it’s all the letters that have gotten lost over time, and they’ve ended up all together. So, there’s a big L, an A, but they might be sat next to an italic, lower case I or something like that. But it’s great. I love them, because their family is somewhere else at the moment, so there they are. So, I used them on the cover, and I like colours as well, so I just overlaid whatever colour – I might do a red A or a yellow A or a blue A and then print a red N holding on to it, so you’d get an orange. And then do it in a square, so the letters can’t be just Anti- Album – you have to sort of squish them in. I did all this before the album. It didn’t say Tony Wright on it, so the label was like “it doesn’t say Tony Wright on it”, but I wasn’t that fussed. The graphics guy, who did it for the album, he put it all onto the template and he scanned it all in and put my name on the bottom of the I, I think it is… so, yeah. It’s just a piece of… it’s just a thing I did with my letters and my inks, but I wanted it to look right.

I really like it – and it makes it so much more interesting having that story. And it’s amazing that labels are still fighting that battle over putting an artist’s name on the cover – that harks back to Beatles and Pink Floyd!

Yeah, it doesn’t who it’s by this album If you buy it and you hear it and you like it, that’s great – that’s what it’s for.