UKofA are one of the latest signings to Trapped Animal offshoot We Go To 11 and, like its parent label, We Go To 11 is an artist-first label that provides a range of services in helping to bring music out in an increasingly challenging environment.

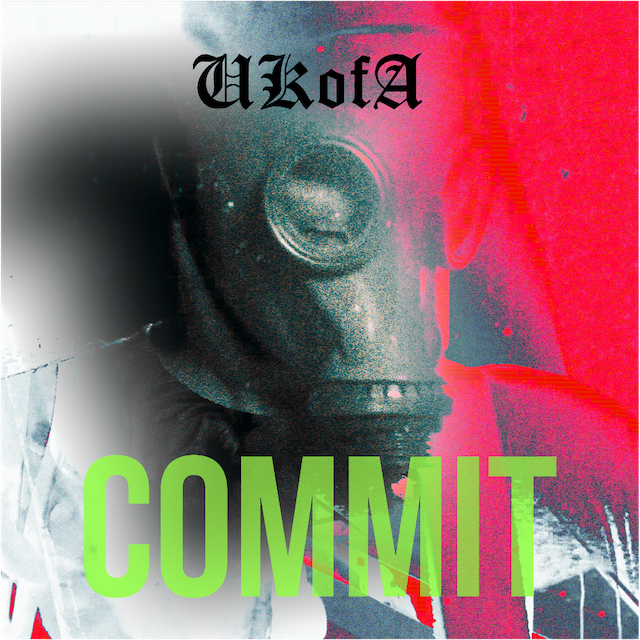

As the name implies, the focus of We Go To 11 is rather heavier than Trapped Animal, and UKofA fits right in, with forthcoming new album Mister Oblivion (slated for a Dec. 5 release) drawing upon a range of influences from Nine Inch Nails and Gary Numan to Alice in Chains and even old school hip-hop. The brainchild of John MacKenzie (Hawk Eyes), UKofA offer diverse and engaging soundscapes, with new single Commit providing only the most elemental tape of this innovative project.

We had the chance to catch up with John, an amiable and passionate artist, to chat about the creation of Mister Oblivion – an album apparently inspired in part by Four Tet videos – as well as the importance of production and the challenge of working as a solo artists, free from the restraint of fellow band members.

Join us as we dig into the world of UKofA

How long have you been doing music, because I was under the impression this was your first solo endeavour?

Where to start? I’m older, you know, and I was in Nottingham in the early 2000s playing in lots of bands there, mainly as a drummer. Like a lot of drummers, there’s always a lot of demand if you can play a bit, and then I moved back to London and joined a band called Godzilla Black for a good few years. That was a really formative experience for me, that was quite an intense collaboration mainly between me and one other guy, and then we branched out to include other people.

That was formative in the sense that we basically had our own rehearsal space that we could use all the time, so we bought recording equipment and just started making stuff ourselves and learning Pro Tools and that sort of stuff – to be, sort of, self-sufficient. Then I joined my friend’s band, Hawk Eyes, and that was so different, because they were doing stuff that already had momentum. We did some nice big gigs in Europe and stuff, we had a PRS momentum grant and stuff, so we got momentum with that. That was a very cool experience, because I’ll probably never do anything like that again, in terms of show sizes and stuff.

That reached a natural ending, where everyone had got to a particular age; some had kids; and you also make a lot of sacrifices in terms of your career and stuff like that, and you notice that everyone else is half-way to paying off their mortgage and you’re not even on the ladder. And then lockdown, I suppose, had an impact. It had a big impact on stuff. So, the whole time since then, I’ve been making music. I’ve been lucky enough that we moved out of London to a place where I could have a little space in the garden that’s my own little spot for making music and stuff. So, this is actually my fourth album, and it just felt like, well I could keep doing it on my own in the garden, but I’d quite like to get back out there. One of the things I really love about music – what got me into it in the first place – was the whole dialogue or conversation between the performer and the listener and, when you’re actually out there doing music, you’re meeting other musicians. It’s just having those interactions and stuff, and I really miss that.

Earlier this year, I did a one-off gig, which I was asked to do at fairly short notice. I threw it together and it was pretty basic, but I loved it and I’d like to do more of it. I’ve got all this music, so yeah, let’s put an album out – let’s do it! And put a bit of money behind it and a bit of effort into it.

Then, the connection with Joel, he was doing like… I’ve known him for years, it turns out, because he was managing bands that we played with, and he was putting gigs on, and then he did the whole Headswim thing. And Headswim were a massive band for me in the 90s. So, I saw him do that, and then he branched out with the sub-label, and here we are. So, yeah, that’s a brief, potted history. Basically, I’ve always been doing stuff – sometimes singing, sometimes drumming, but this stuff at the moment is just me and, yeah, I want to get back out there, kind of before it’s too late. So, yeah, it seemed like a good time.

One of the things I’d like to dig into is that there was this sort of enigmatic comment about watching Four Tet production videos, and that fed into this album. Can you elaborate on that?

That’s a great question, because I’ve never really put it in context. But I think actually I knew… I had the tools there already, and I always messed around, particularly in making demos and stuff, with looping and stuff like that. I’m doing everything in Pro Tools which, you may know, is very linear. It’s the new version of a mixing desk and tape. You record in a line. And I was… I played around with things like Ableton, but I prefer writing the songs in this more classic kind of way.

Then I watched these Four Tet videos, and he was in Pro Tools, just messing around. He was basically a guy like me who could have been doing what I was doing, but he’d gone this particular route, and he was just taking stuff from everywhere. One of his big things was taking music from DVD menus – the kind of thing you’d fall asleep to and then wake up at 4 in the morning with it still playing! But he was just putting it in Pro Tools and mixing it then and there, and it wasn’t even like the most up to date version. And I wanted to have a go at that as a way of inspiring myself. So, I got some library music and stuff like that and then just random samples. And I started playing around and building up these loops a bit more, using these tools in Pro Tools like time expansion, which are really fun, but pretty basic compared to some software. So, you get quite a granular feel with your samples when you’re playing around with that. After a while, I had ten of these ideas and I thought that maybe there’d be an album in it. And, at one point, I’d spoken to a friend to maybe do some vocals, and we had some ideas, but it wasn’t really doing anything. Then I figured I could go in and do the more conventional song writing aspects of it and start layering up the bass, guitars, synths and stuff like that, and that’s how I got to where we are.

There’s still a mismatch of stuff in there. Not all of the songs are built that way. Some of them were kind of older demos that I then start layering new material on, ore replacing guitar lines with synthesisers. Hope Assassins is basically that – it’s fairly obvious that it’s a rock song, but the production is… I was taking out the more traditional elements and seeing how far I could push that kind of stuff. And also, we’ve got a piano in our house. So, that was another thing – I figured I might as well use it.

Then it was a process of… I ended up with eighteen songs being mastered and I was originally going to put them all out, do it as a double album and it could be my Mellon Collie! I did know, but someone did say to me, “if you want people who’ve never heard of you, you’ve got to be really respectful of their time, so try and hone it down!”

So, yeah, that’s what I ended up doing.

Anyhow, that’s broadly where it came from and from those origins of being inspired by watching Four Tet – just a different way of doing music than I had tried before.

I find this sort of mode of production is really exciting – when you have an idea in your head and you’re trying to do things that are right on the cusp of your skillset (or possibly outside of it), but you find your way to it. And the result is that you kind of get the sound in your head but also, through happy accidents along the way, you get something more than that, which helps to define your sound in the process. Is that what you found here?

Absolutely. Yes, absolutely. A lot of it was just experimenting, layering stuff up, finding those moments where it becomes more than the sum of its parts, I suppose. And then isolating those and constructing things out of that.

Sometimes, things happen very easily – very quickly – and it’s almost too easy. And sometimes it’s a real slog, but you know that there’s something there. The last song on the album, Time Will Take This All Away from Us. It started with a drum loop and it’s the longest song, but it wrote itself very naturally. Other songs like the second one, Flesh, that was something completely different for a long time. I loved it, but it wasn’t doing anything. Then I figured out a completely different way into it, almost a folky kind of melody on top of this noisy hip-hop thing, and then it felt like we were getting somewhere. But it took a long time.

I mean years, really, for some of these tracks. But yeah, like you said, there was a lot of pushing myself and figuring stuff out. It took longer to do this album than any other than I’ve done. The last album that I made, All This for A little Peace, that was very much an album where I went to the studio and everything was demoed, and I went to the studio to record everything as well as possible. The drums are the main thing. You get a good drum sound, and everything follows from there. But this one was weird and headache inducing at a lot of points. But I got through it in the end!

It sounds like you’re the sort of songwriter who’s always fiddling away with things in the background – and it’s always interesting to return to an old demo, like you did, and swap out a single element and suddenly it makes sense. I guess that’s why it’s so important to keep hold of work-in-progress.

Absolutely, yeah! Actually, you’ve just reminded me that there was one song that didn’t make it onto the album because there wasn’t room, but it’ll come out at some point. But it was a riff that I wrote when I was sixteen. I always loved the riff and at one point it was almost like a Korn rip off… but yeah, absolutely, there’s always stuff that I’m working on. You sort of learn a lot form the song writers that are your heroes and one for me has always been Thom Yorke form Radiohead. He’s never been afraid to sit on a song for twenty years or something, until he’s got a way in that he’s happy with. So, I’ve always taken a little bit of inspiration from that, if I’m plugging away at something that’s just not working.

I guess part of what comes with experience is knowing when you can park something, or when you should park something, or realising that you can find a way through, but you need to work at it. Some of the songs I was working at for a long time, and I was convinced they’d be on the album, and they were among my favourites, only to get to the end and realise they didn’t fit! Fortunately, I had a lot of material, and it was OK. It’s when you don’t have enough, I guess, that you end up with things that you’re really not happy with.

Yeah, I love it! It’s interesting because, going back to what you asked me about – my roots and stuff – I never saw myself as a sort of “song writer”. I was much more of a rhythmic musician playing drums. I did play guitar, but I wasn’t particularly good. But over the last ten or twelve years, I’ve really kind of grown into a love of song writing in all its forms. I usually – I haven’t got it right now – but I work out there and I have to do a lot of phoning and stuff where you’re just waiting, so I have a guitar that I just pick up and play. And I got really into finger picking and stuff like that just from not having a plectrum sitting around. There’s not much of that on this album, but I think the next thing I do will have a lot of those kind of songs. And just really listening to songs and how they’re constructed and stuff, it’s incredible. Yeah, a beautifully constructed song is just a wonderful thing.

I guess, as a solo artist, there is a danger… when you’re in a band, you bring a song t the room and everyone looks at you and after, you end up shaving three-minutes off. When you’re on your own, there isn’t that safety net. Did you have anyone to help?

I relied on myself but, because I don’t have any pressure of time or anything, I was able to set things away for weeks or maybe even months, so you’re almost coming at it with a bit more objectivity. And, again, I think that, with the experience, and having been in bands with people, I’ve learned those skills of being a bit brutal sometimes and just accepting that things need to come out, even though you love it. And maybe you park it and it ends up in another song…

I guess, I did it on my own, but I wouldn’t have been able to do it twenty years ago. And, in fact, I listen to stuff I did 20 years ago. My old band, Godzilla Black, did an album called The Great Terror. It was our second album and that was kind of when I was veering into song writing more like this. Now, when I listen to it, there are so many ideas on there, but I can hear that the songs would be better if they had had a producer just telling us to take two minutes out here or there.

The one thing I did – I did send the album to a trusted friend, a guy called John Morrisey, because originally there was another song on the end. I loved the song, but he pointed out that the album essentially had two ending tracks and it just wasn’t necessary. And I listened to it, and I realised he was right. And it was hard to lose it, but it’ll come out at some point, so I’m not too worried about it.

I think also, particularly where there are a lot of ideas and information going on, it’s probably better for it to be a little bit condensed for the listener. And I’m aware that these songs are different. It’s not like I’m writing in one style and there’s one sonic template. There’s overlap, but you don’t want to completely exhaust people when they’re listening to it.

So, yeah, I managed it myself, but I also had to manage myself. [laughs]

I definitely think that way. I take off my song writer hat and put on my producer hat and try to imagine what a producer would say. And hopefully I get it right.

Did you both mix and master it?

I mixed it. And that’s a good point because, when I first sent the tracks to Joel, he was very diplomatic. He said “I’m really into it” but, and I can’t remember how he phrased it, but he said “there’s something about the mixing…”

So, we got a professional mixer to do a consultancy, and he came back with notes. And he was so good. Like, because he was very careful to not say “you’ve messed this up”, and it was really good for me to have someone’s objective, professional opinion. So, I went back and did a final pass at the mixes and that really improved them.

And then a guy called Christian Browning – he goes by “Big C’s Production”, he did the mastering, and he had already sort of set up mastering chains for the early mixes I did and, when I sent him the new ones, he said that the difference was definitely there.

One thing I did, in terms of mixing and mastering, is I took everything off my master bus – anything I was using. Which I know… there are different trains of thought about how you do this stuff. I took it all off before the mastering, so he had quite a lot of leeway to do as much multiband compression; all of that mastering wizardry that he wanted to do. And I was quite happy for him to have an input into the overall sound. Again, because otherwise it’s just so hard to be completely objective when you’re doing every aspect of it yourself.

Yeah, I think it’s definitely a rabbit hole you can go down. I suppose from a mastering perspective, it is a varied work. It has a coherent sonic sheen to it but, straight away, the first track hit me as having this kind of Filter / Crystal Method vibe, whereas the second track – which you mentioned earlier – has this Alice in Chains angle to it…

That’s actually very cool. I must have been listening to Alice in Chains and thinking they were amazing. But that’s definitely in there. They use 4ths for their classic harmonies, so I was figuring out what that would be and singing those. That’s definitely in there. There’s a guy called Richard Dawson, his stuff is incredible. He’s from Newcastle, that sort of area, and there’s a whole group of musicians. Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs – they’re like the heavy band. But they’re all amazing. There’s a whole group of musicians and they’re all doing different things, but there’s like a vibe coming out of it. And, yeah, that was definitely an influence for that song. Because I was trying to figure out why it had this quite cool hip hop beat, but I didn’t want to put out a hip-hop track. So, I was sitting down with a guitar, just listening to folk melodies, trying to understand why a folk melody would go with this beat. And I was trying to figure out from a musical theory perspectives – how they use major and minor to change key almost within a phrase and stuff like that. That’s quite interesting and then trying to apply that. So, there was a cerebral element to that, but I really love that song. It’s got those really noisy, squalling guitars that’s kind of coming up and down through it. So, yeah, I was really pleased with how that came out.

But it also works really well if you’re just sat with an acoustic guitar playing it. And I was really keen for it to be possible to do that with all these songs. I still have to figure it out fully, but I like the idea of doing it acoustic or with stripped-down arrangements. It would be nice to play these tracks live in a low-key format. It doesn’t have to always be, like, rock!

Sorry – I do go off on tangents!

I’ve always found hip-hop beats work surprisingly well with industrial and heavier music.

Absolutely. I mean there are so many bands we could list, but like Rage Against the Machine is a big one. And also, like, when I was younger – Senser, they had that; and then harder hip-hop stuff, like Ice Cube and Wu-Tang Clan and stuff like that. Someone could probably explain it, but there’s something about the syncopation in those kind of beats which goes well with a guitar riff. It’s interesting, because Limp Bizkit are having a renaissance recently. They were derided for years, and they are sort of a ridiculous band…

…I think they know that though!

They’ve leant into it, haven’t they. I mean Wes Borland, who’s a great guitarist, I think wanted to do more serious stuff and he left a few times; but now he seems to love it and it’s great. And they’re playing basically hip-hop grooves under his riffs and now they’re getting arenas and fields full of people moving. It’s very funny how stuff comes back around. There’s definitely something there.

I mean the hip-hop thing, that was in my head quite a lot. And that was coming from, I mean you wouldn’t classify Four Tet as hip-hop, but there are certainly elements of that there. And then, from the start of the project, having these more electronic beats, that kind of fed into why there’s samples on there. And I already mentioned Ice Cube and Wu-Tang, but they always had film samples and stuff and I loved that. At one point, I was thinking the whole thing would be a mix tape and I could just drop in bits of the additional tracks. But actually, I decided it should just be an album, but there are still samples – the ones I thought really worked – and then I had to find samples for my thing – there’s David Lynch, Cronenberg, and the Cohen Brothers right at the end. So, that’s my nod to 90s hip-hop and that kind of stuff.

It’s kind of hard now – it’s a lot harder to use samples. I’m not sure how much clearance you had to get, if any?

I’ve not done anything like that yet. I’ve uploaded everything to YouTube to see if I got a Copyright claim come through. I’m not using the samples in a musical sense – it’s not like I’m sampling a piece of music and making it front and centre of my tracks. I’m using dialogue samples from films and recontextualising them. If I did get a takedown notice, I’d probably contest it on a fair use basis. If I have to just take it off, I have to take it off, but it doesn’t really affect the songs that much. That’s what I’m thinking anyway. I have used samples on previous albums, had copyright claims, and then I’ve argued fair use, and they were like “that’s fine”. So, we’ll see how we go. But you’re right, things are definitely tightening up. And now you’ve got AI bots that’ll just search YouTube for anything remotely using somebody else’s material, so the chances are higher that I’ll get a claim. But I’m OK. I feel that if it’s getting to somebody’s ears, then it’s not a bad problem to have.

At the moment. No one’s really heard my stuff. It just means somebody’s heard it, even if it’s only an AI bot… I don’t know, maybe there’s some justification in that! Anyway, I’m going to take the risk, but y9ou may find me having to re-record things!

I suppose the crazy thing now is, with AI tools you could re-record a sample in your own voice and then get an AI tool to say it in the voice of an actor. It wouldn’t technically be the same master recording! It’s bound to happen at some point. We’re in crazy times!

We were joking the other day because someone had done a funk version of Metallica’s Black Album and my friend said he wanted to hear them do Blackened from And Justice for All. Anyhow, yesterday, what pops up on my YouTube frontpage? So, I was listening to the AI funk version of Blackened, and it was pretty good!

I remember reading this interview with Trent Reznor and he was talking about how the band evolved from Pretty Hate Machine to the live band that followed in its footsteps, and he said he wanted a more “visceral flex of the muscle” (I can remember it pretty much word for word) – is that how you want to approach this music? Would you consider a band and, if so, would you keep the electronic elements, or jettison them in favour of a rawer feel?

Yeah, absolutely, I’d love it. And I am going to… well, I’ve started talking to people already. What I think I’d like to have is a sort of scalable version of it. I’m investing in a bit more equipment now, so I can do a one-man version. It definitely lends itself, as an approach, to these newer songs, because they are quite electronic. Some of the older stuff, that’s more like live band and stuff so they either need re-arranging, or I don’t do them. But yeah, I guess, I’d like to be able to bring people in and out depending on their availability.

People are busy! And good people are already involved in projects and stuff. So, a slightly woolly answer, but yeah, I’d love to be in a situation where, if the bass player can’t make it, but the drummer and guitarist can, then I could bring different stems in to make it work.

So, I’ve invested in a new sample playback machine to do that. It could just be me and ad rummer at some points, or it could just be me. If a good opportunity comes up, I’d like to be able to do it and not miss it because a guitarist has to go to a parent’s open evening or something. Which is totally fine and reasonable, but yeah, watch this space!

I think, to start off, it’ll just be me. That’s what I did earlier this year. I used a bunch of equipment I already had. I had an Alesis sample pad, and I was running my tracks off that, but it took ages to get the tracks to load, so I’ve updated and have this Korg sampler thing. Yeah. I would love to get back into a band where it’s actually like… you’re not beholden to a click or whatever – it’s people in a room. And that might happen, but I’m not holding my breath because it’s so difficult and also, we’ve moved out of London. Not too far, we’re in Hartford now, but there just isn’t the same amount of people. So, yeah. But I also like the idea of just being able to turn up to a gig with a couple of cases, get the train there, and just set up my stuff on a little table, play my set, and then get the train home again. Not worrying about cabs and speakers, which takes up so much of your energy. You get on stage and you’re already knackered!

So, my last question – this kind of music really lends itself to remixing and I was wondering, a different way of looking at the musical community is getting people involved in remixing your work, so is that something you would consider or have considered?

Yeah, a little bit. A friend of mine has got really into modular synths and patch bays and he’s really good at it. So, for the next single – it’ll be next year sometime – I’m going to send him stems for Commit, which is the next single, and he’s going to have at it! But yeah, I’m totally. Up for that. I’ll have to do all the stems and everything if I’m going to do the live performances anyway. I do remember that, at one point, Nine Inch Nails did a thing where they put up stems for one of their albums. Yeah. I’d definitely be up for that if people were interested and wanted to do it.

Particularly because of the way I make these songs, they’re always evolving, they’re never quite finished. Actually again, with Commit, it’s slightly different, but I got Ben Koller, the drummer from Converge to record live drums for it, because I thought it would be a cool track for that. He’s like a lot of these guys, he’s an incredible drummer, he’s got time between tours, and he’s got access to a studio. So, I contacted him in LA, and it was relatively inexpensive for getting a guy like that. So, at some point, there’ll be a version of that song with that on. So, yeah, that’s what you used to get with CD singles – it would be the same song a few times. Like Faith No More did it and there was a Rammstein remix. So, yeah, maybe. I mean, I guess the only thing that tempers that for me is that you’ve got limited time, particularly because I’m doing most of the stuff myself. If it’s something I can give to other people and they’re into it, then that’s perfect. If it’s on me, then I have a lot of songs I want to finish. But you never know, if a song got into people’s ears and they wanted a different version, then maybe; or if people wanted to mess around with it, that would also be very cool.