Some interviews, through no fault of the participants, are just a nightmare. On this occasion, whilst reaching out to Geoff Tyson, it was technology that conspired to strangle the discussion as the phone system repeatedly cut out over the course of the thirty-minute chat. Happily, Geoff weathered the vagaries of technology, even going so far as to kindly phone me back after the call broke down for the third time in as many minutes and we were able to finish. Nevertheless, if the flow feels a little bit uneven at times, it’s because we were cut off mid-sentence, for which I can only apologise.

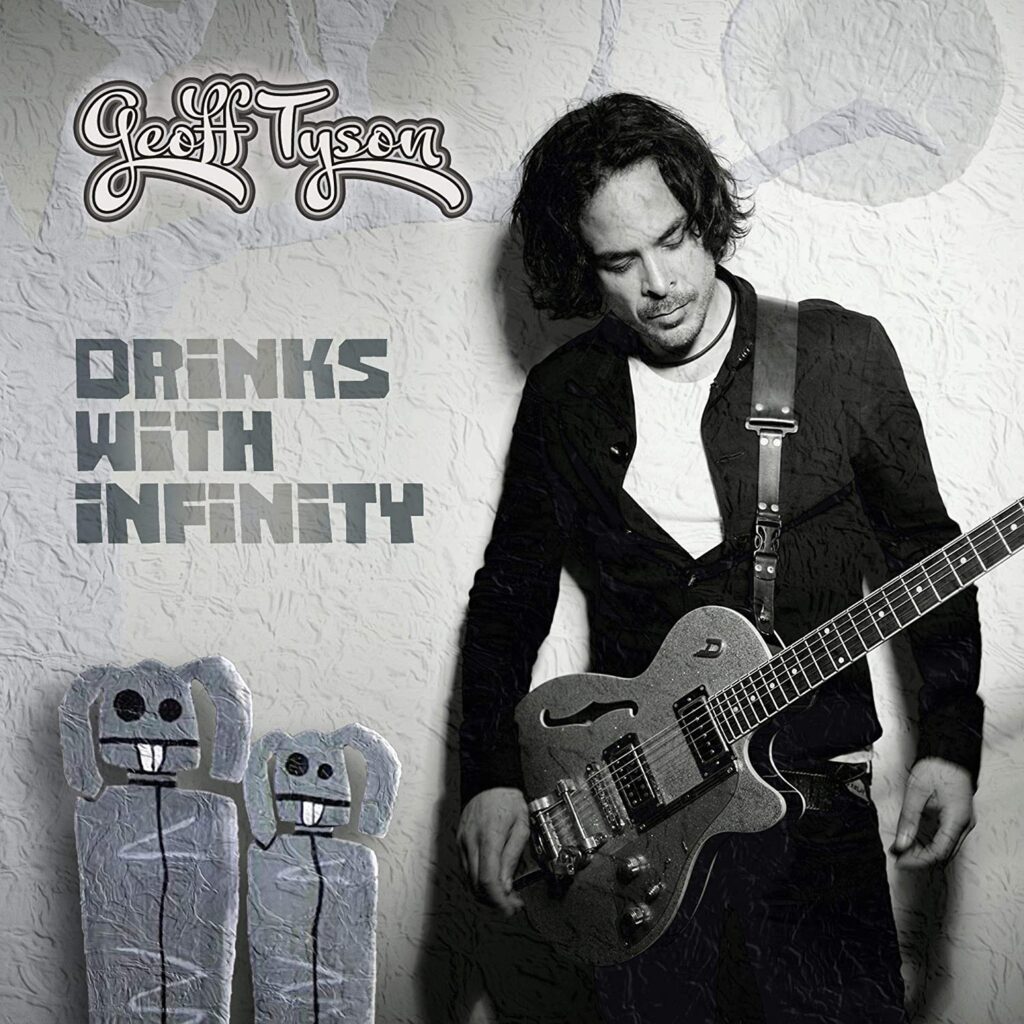

Geoff is a Californian guitarist, now living in Prague, who studied under Joe Satriani and cut his teeth in the highly regarded T-Ride before a stint in the industrial rock powerhouse Snake Water Conspiracy led him to form Stimulator. A hard-working musician, Geoff’s relocation to the Czech Republic has seen him tour Europe repeatedly, developing a strong reputation as a guitarist of note, and his latest album (Drinks With Infinity) is a self-produced instrumental venture that is sure to burnish his reputation still further. An album that emphasies just how fun an instrumental guitar album can be, you can read our full review of Drinks With Infinity here. Meanwhile, read on and meet Geoff Tyson.

So, my first question is about how you found yourself living in Prague?

Well, you know, it was an interesting journey. It started in 2007 after President Bush was re-elected to office. I had some turmoil in one of the bands I was working with at the time, and I kinda reassessed my opinions of what success would mean. I mean, in the past, it was always considered that if you didn’t have a hit American record then it didn’t really mean anything, and I had to reassess that. I’d just released my first solo album at the time, and I was thinking what was keeping me in the country. Aside from the economy crashing, I felt that the political situation in the US was veering a little too far away from where I felt comfortable, and so I started looking to Europe and my first thought was that it’s easier to tour in Europe because the cities are closer together, there are international train networks and, being a generally impulsive person, I just sort of said fuck it; bought a plane ticket, sold my Harley and most of my possessions, put a suitcase together, my guitar in a bag, and got on an airplane to see what would happen.

I landed in Prague because it’s more or less in the middle and I figured it would be a good home base. Then, I spent about three and a half months touring around Europe and, in addition to representing music from that album live, I also wanted to find a culture and a city that I thought would resonate with me personally. I figured an American dude with a guitar would be in a pretty good place to start communicating with people and I’d get a really good idea of what the cultures were like. I played in every café and hotel lobby and street corner and club that I could connect with, and I had some amazing experiences and met some brilliant people.

I think it was in Barcelona that it started to get cold and I’m from California, so my idea of winter clothing is long pants and converse shoes and a thin motorcycle jacket – I was pretty stunned by what winter really meant, so I shut down for the winter season, came back to Prague and I figured that I’d sit that period out. During that winter, I really connected with the culture and the city and the people and decided that that was where I would stay. I still have friends form all over Europe and I go and play shows in the clubs with the connections I’ve made, but Prague fits very well with my personality. It’s a big city, it’s cosmopolitan, people are nice, so I stayed and here I am.

That’s so cool – it seems to be such a creatively fertile city, especially when you get off the beaten track and start exploring the less touristy areas…

Yeah, there’s just such a high regard for artists and musicians here. I came here in 2007 and coming here from the American paradigm where, if you want to get on the radio, you have to go through some sort of business process, but I found that here anything was possible. There wasn’t any kind of corporate consolidation of radio stations, so to speak, if they liked your tune, they would just play your song. I ended up connecting with photographers and film makers and I was doing music videos at a fraction of the cost that I could have done in L.A. and the first music video that I released here, went a bit viral, and suddenly I was getting calls to headline festivals in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Germany and Hungary and I just thought: this is easy! What a concept – that you don’t have this weird stranglehold of corporate power on art here. I put a band together with these fantastic musicians and wow! I found myself headlining, like a music festival on a lake, in Hungary, on a Saturday night and thinking “how hard would have been to get to this point in the United States?” So, yeah, it was a very, very warm welcome and I’m very happy to have discovered that contrast.

I always found that Eastern European audiences are really invested in the artists they go to see and I think it’s really cool for artists to be met with that warmth and openness, as opposed to the cynicism that seems to be commonplace elsewhere.

Yeah, and they actually listen. Maybe you’ve seen the contrast between, say I played at the London Borderline many years ago and, you know, you feed off the energy of the people in the audience. I don’t know if it was intentional or a “cool” thing that Londoners do, but people seemed profoundly bored. And even though, after the show they’d come up to me and say they loved it, so I guess they were enjoying the show in their own way. But playing to a Czech audience or a Polish audience, they lose their fucking minds and they’re jumping up and down and it reminded me of playing in the 90s, back when rock ‘n’ roll was king, and it reignited that initial feeling of “why am I catering to American audiences? What is it about that? Why would you discount these wonderful people?” So, yeah, it was very welcoming.

Something else I wanted to ask about was a single from a couple of years ago – Spotlight – which is a very powerful piece that captures that juxtaposition between the artist’s need to perform and how it feels to be caught in a spotlight, and I thought that was a very profound subject to deal with…

Thank you. Thank you very much. That was actually inspired by a combination of events. Chris Cornell’s suicide and the question of how it could end like that. There was also my life – I was having a kind of difficult time and I wanted to contrast what you see on the stage, which is theatre. You’re presenting yourself not as you are, but as any artist knows, after all the smiles and headbanging and “are you ready to rock” you go back stage to a toilet that hasn’t been cleaned in six months and this dank, dirty tour bus and then it’s the same thing every day and it’s difficult to meet friends and the people who you do meet, it’s not really a connection and people don’t really realise what it’s like to be a performer and how depressing it can be. So, in this video, I was working with this Czech director – Krystof Kalina – and were talking about these sorts of concepts and it was his idea to have the performer kind of pop and he paints himself up as a clown as his final performance and it’s his suicide. I was completely blown away when he showed me some illustrations and I said, “you just do whatever you want – I’m not going to be a backseat driver!” So, that video was al him and I was just stunned when I saw the final and the actor – Geoff Fritz – he’s an American guy and a fantastic actor. I showed him the script and he said, “you know, I’m going to fucking kill this!” So, yeah, I wish he would do all my videos actually, but he’s too good and he’s become too popular.

One of the reasons I thought about that video and wanted to ask about that before you got to the current album is that, with the lockdown, we’re in that weird position where, as performers, there is that isolation when you’re on tour, but on the other hand there is that need to get out there and I was wondering how things have been over there for you?

Well, yeah, there’s definitely a new paradigm. My feeling was that we were doing what we had to do and that, in the grand scheme of things, my own emotions of boredom were really kind of a needed sacrifice. It had to be done and I just had to fucking deal with it. Different artists coped in different ways at first and, when it first started, I said I was going to be super-creative, finish a bunch of songs, do music videos and fight it… and then, I don’t know, maybe two weeks into it, I was just like “fuck it!” You know – sleep all day and be a sloth!

[At this point the interview dies completely]

So, yeah, you’d turned into a sloth… and then the internet turned into a sloth and you disappeared!

I feel like, personally, I can’t be artistic in a bubble. There has to be contrast. You have to go outside; you have to experience things. The artistic process, for me, doesn’t work if I can’t… For example, I’m a long-distance runner. If I can’t go out to the park or to nature and run to clear my head, then it means that I don’t have anything to say. I don’t have any fuel to burn that creative fire. So, I mean…

[The connection, apparently just waiting for the perfect moment to strike, collapses once again and the only sound is of me banging my head against the wall. Happily, Geoff calls back and we continue where we left off…]

I don’t think I’ve had this many problems in an interview, perhaps with the exception of a Cannibal Corpse interview where we got moved on by the police…

[laughs] Wow, that’s a cool story.

So, moving on to Drinks With Infinity – it’s very interesting writing instrumental song sin general because you have to fill that void where lyrics would traditionally be, which is a challenging thing to do, so I was wondering how you initially approached the material.

Well, it was an interesting discovery process for me because, I’ve been writing vocal music for so long and when I finally decided to do an instrumental, I had about fourteen tunes with melodies in mind and I went into a studio with a drummer and tracked them all, bought them home and they were all useless! They were all terrible and it was just such a different paradigm because, for example, when you’re singing you can sustain a note and feel like “oh yeahhhhhhh” and somehow that works, but you can’t do that on a guitar – you can’t fall back on any kind of lyrical concept and so I ended up scrapping all fourteen of those songs and starting from nothing. I really didn’t have any idea of what would work, so I just kind of plugged in a guitar and started improvising until I though that maybe it could turn into something and that was really how the whole album was created. It came from a more stream-of-consciousness thing, actually with the guitar, rather than planning it out like a producer. So, yeah, there were a lot of false starts and a lot of things that I did that I think are really interesting pieces but couldn’t actually get them to work in the guitar context. So, yeah, it was a very new process for me.

I may be misquoting, and I’d have to go back through my records, but it may have been Walter Trout who said in an interview that, when you play a guitar, you’re trying to emulate the human voice, where each solo has that sense of wailing and roaring, that’s just interpreting emotion in a different way and I was wondering how that concept resonated with you?

You know, it was that I really wanted to focus on the compositional aspect first. It was a challenge. Usually, I write on an acoustic guitar so when I had the electric guitar and the amp was on, the microphone was on and I’m going in to Pro Tools and I was thinking that I wanted to play something that was a product of the instrument – that it had this many strings and frets meant that I would choose notes that I wouldn’t necessarily choose if I was singing, so I had to keep in mind that it might be a very interesting and fancy way to play something, but not necessarily a good song. So, yeah, it was a very strange challenge and for me, music without interesting rhythms, dynamic changes, and things like that, really… I have a low attention span for that kind of thing. So, yeah, sometimes when you’re screaming in the solos and stuff, it can be very emotional in a vocal kind of way, most of the song is playing little chords and riffs and making it sound like a steam train or a motorcycle or something. And that’s one of the great things about electric guitar – infinite possibilities for tones and so on. Yeah! I don’t know if that makes sense.

Yeah, that makes perfect sense and, on a track like Six Weeks of Tina, it sounded like you were either using a lot of effects or layering guitars over one another to get the sound that you described. So, you were producing the album, and you took this very physical approach to making the music?

Yeah, that song is an example. I don’t know if you’re familiar with my first band, T-Ride, but we had a song called Bone Down, which is an instrumental. It wasn’t a traditional kind of blast beat, shredder kind of a song. It was mostly rhythm guitars and I wanted to create something that had a similar kind of feel. That song is just one guitar with some drums, and I think there’s some keyboard in the chorus or something. I wanted to encompass all of the melodic and rhythmic parts just from that one instrument, taking themes that repeated for a verse and some choruses, but played completely differently with different rhythms. That song started as an improvisation. I think I had a drum beat and just vomited out a guitar part and some of the original improvisation is included on that track – I would listen back to the improvisation and find that it was really cool and then write the song around that. Then we just worked at it until it was a coherent piece.

I really like it when you’re composing something and, of course, the artist’s prerogative is to take the original sketch and worry at it until it’s perfect… but sometimes you capture something really special in that first expression of an idea and you can never get it back again quite the same way.

Yeah, that’s very true and there were times where I was tempted to say that a guitar wasn’t entirely in tune, or that it wasn’t exactly on the beat. And, you know, you can fix those things in Pro Tools, but I resisted all of that. I cold have made it perfect and turn it into a Justin Bieber song, but that’s not what it is! When I was doing research before I started on the album – I was on the internet looking at other guitar players – there are some absolutely stunning guitar players on the planet today – amazing talent – they play perfectly and it is some of the most boring music I’ve every heard. This was something I intentionally wanted to avoid. Even in my choice of guitars. I have like this shredder Ibanez, but the guitar I sued mainly on this album is quite difficult to play, it’s not fun. It’s not a shredder guitar, it’s a Frankenstein thing that I put together and because it forced me to really punish the instrument in order to get the emotion out and when that emotion combined with the fact that it wasn’t going to be fixed in the end, I thought that was delivering a level of emotion that would have been lost if I had tried to make it perfect. Does that make sense?

Yeah! I started out with alternative rock and one of the things I always got from that is that you can get too lost in technique and you lose a lot of the humanity and I think there’s a balance to be achieved between technical ability and the soul of the song – whatever the song is – getting that sense of that humanity is more important to me.

Yeah, I think it comes from different parts of the brain – you have that emotional monkey part of the brain, which is just in the moment and then the analytical part of the brain, which is always wondering whether the music will be considered modern and whether it fits into what you’re supposed to be doing. I found that concern that I was always drawn to the more technical side of things and I had to shut that off. I would work all night, do a track; then go to sleep and if I heard it before consciousness hit and I liked it, then I knew it was a keeper regardless of what mistakes might have been in there.

One of my favourite tracks at the moment is Monkey Love – that has some wordless vocals on it, right?

Yeah, there are some la la las on there. A Slovak singer was in this studio, where were recording, and we were probably drinking beer or wine that evening, and I said she had to do something, which she did, and I put it on the album.

I like it, it adds something to that track, it’s a really cool song.

Thank you. Well, I wanted something with that [sings] kind of rhythm, but you know, her voice is soft and breathy and I felt like it could add that extra syncopation without the tone dominating from a piano or whatever.

So, how long were you in the studio tracking and mixing?

Err, that’s a good question actually. I think it was around a year. As I said earlier, there was a lot of work that I did that was really a false start and then there was some composition that I had written a long, long time ago that I rediscovered. There was one funny instance – I got an email from a South Korean commercial production company and it said “hey, we fond one of your songs on Soundcloud and we ant to use it!” And I thought “I have Soundcloud?” But, apparently I uploaded some things and then forgot about it and it was all songs that I had started and never finished and I was listening through to some of them and I thought they were kind of cool tracks that I should do something with, and they actually made it onto the album. I found the sessions on the vault computer. So, yeah, not counting the work I did in 2003 or whatever, I guess about a year was the production time for this.

So, with all the pandemic, have you had thoughts about how you’re going to promote this album?

Honestly, right now, I don’t know. All my shows have been cancelled through to the end of August and, you now, there are so many artists right now who have no idea what to do. We’re all waiting to see. In some ways, people are creating their own opportunities to live stream or busk any way they can, even just now, the Czech Republic did a great job with the pandemic and the clubs, I think, as of a week ago, are open. But we couldn’t go to Hungary or Slovenia or any of the Baltic countries. We can’t tour there, so it’s difficult to plan… I don’t know. Currently, I’m just waiting to see, and I don’t know! I may come up with some brilliant new idea that changes the music industry – then I’ll tell everybody!

Drinks With Infinity is available on 31/07/2020

Official Biography:

Geoff Tyson started his musical journey at the age of 3, when he started classical piano training. He played until his early teens until he heard Eddie Van Halen and he knew that guitar was his calling.

At 13 years old, Geoff started studying guitar with Joe Satriani, and refined his skills jamming with high school mates Alex Skolnick, Charlie Hunter, Jude Gold, and Joshua Redmond. Geoff is one of two students Satriani has said ‘Graduated’ from his lessons (the other being Steve Vai.) During one of his last lessons, Joe gave him a cassette of his then unreleased album “Surfing With The Alien” and Geoff knew Joe wouldn’t be teaching much longer.

Geoff started writing and recording music at 15, and in one recording session, met Eric Valentine and Dan Arlie and went on to record for years with the band that would become T-Ride. The band was formed in 1986 and went on to release their self-titled debut album on Hollywood Records in 1992.

Geoff recorded and toured with T-Ride for until 1994, with music videos featured on MTV.

Songs from the album also featured in various movies and television shows including Luxury Cruiser in the soundtrack of 1992’s Encino Man, Zombies from Hell in the movie Captain Ron and Bone Down in an episode of Baywatch. T-Ride toured the world with Ugly Kidd Joe, Joe Satriani, White Zombie, Tora Tora and Asphalt Ballet.

After T-Ride disbanded in ‘94, Geoff continued as a recording studio entrepreneur and producer. He wrote songs for HBO, MTV, UFC, and had his songs featured in TV commercials for Blackberry, Macy’s, and Lacoste.

Tyson went on to perform and record with Snake River Conspiracy who’s debut album was released on Reprise Records in 1999, and toured with Filter, Monster Magnet, Queens Of The Stone Age and A Perfect Circle.

In 2003, Tyson created the band Stimulator with singer Susan Hyatt, and they signed a record deal with Universal Music in 2005. Stimulator had songs featured in the Walt Disney Movie “Ella Enchanted”, MTV’s “The Real World”. Stimulator toured the world with Duran Duran, The Go-Go’s, and were featured performers on the Van’s Warped Tour.

In 2007, Geoff moved to Europe and toured with the Geoff Tyson Band, releasing several albums, touring with Nazareth and Fun Lovin’ Criminals.

Geoff now lives in Prague, Czech Republic where the Geoff Tyson Band hit the top of the radio charts. He continues to play festivals throughout Europe.